ZTF Faces: Summer students and their mentors

Jasmine Li (Carnegie Mellon University)

Jasmine Li (Carnegie Mellon University)

My name is Jasmine Li and I'm a freshman at Carnegie Mellon University, where I study at the

College of Engineering. I grew up in Montgomery County, Maryland as an avid reader, and

was fascinated by the many astronomy books I came across. I began studying

astronomy in earnest after competing in a Science Olympiad astronomy event and I'm really glad for the

opportunity to do research under Dr. Quanzhi Ye, a professor at the University of Maryland, College Park this summer.

Outside of work, I likes to crochet, run, and draw.

Quanzhi Ye (University of Maryland, College Park)

Quanzhi Ye (University of Maryland, College Park)

I am an astronomer at the University of Maryland and a long-term visitor at Boston University.

I am primarily interested in the small bodies of the Solar System – asteroids, comets, and meteoroids.

These objects are pristine remnants from the early times of Solar System and can help us understand

planetary formation, migration, and evolution.

I was captivated by the stars when I was a child. I still enjoy going out for (non-work-related)

stargazing every once in a while. Besides stars, I also have a passion for music. I have played

violin, viola and cello in various orchestras and string ensembles as I move from China to Canada

and then the US. Most recently, I played viola and cello in Caltech’s wonderful Chamber Music program.

In Search of Potentially Hazardous Asteroids in the Taurid Resonant Swarm

The Taurid Complex, outside of the comet 2P/Encke and several meteoroid streams, is theorized to contain near-Earth asteroids within its bounds. Due to gravitational influence from nearby planets, many objects are concentrated in a small portion of the orbit, called the Taurid swarm, which approaches Earth in certain years. The hypothesized origin for the Taurid complex is from the breakup of a giant comet due to the many large, meter-sized meteors within the complex.

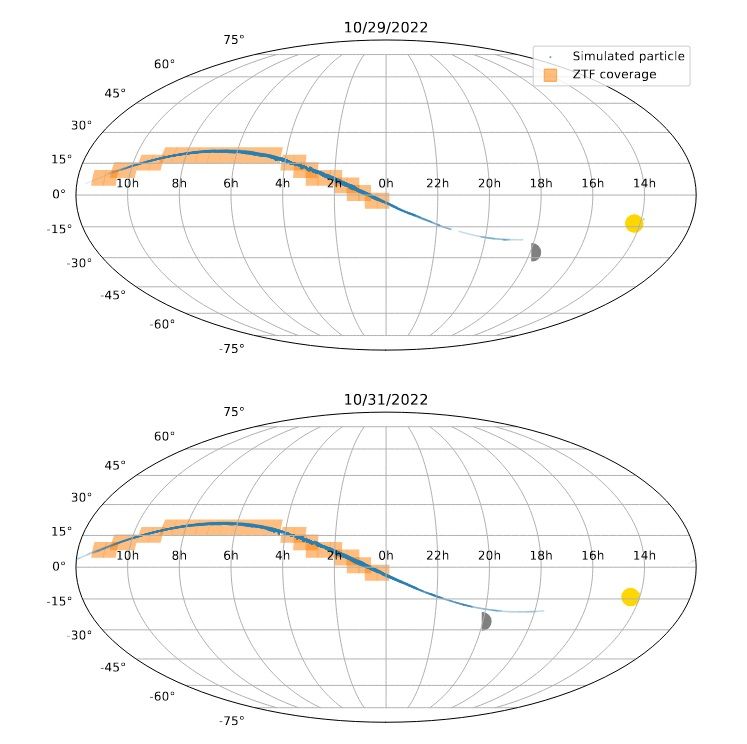

Using data from the Zwicky Transient Facility, we studied data from two nights in order to search for transient objects that could possibly be a part of the Taurid swarm. Using Python packages such as SEP, as well as the ZTF streak database, several filters were placed based on estimated orbits, locations, and trajectories of particles within the swarm.

Our search was by no means exhaustive, but from our non-detection results, we concluded that there were no more than 9-14 objects with a diameter greater than 100 meters within the Taurid stream. Thus, the estimated size of the progenitor comet would’ve been around 10 km in size. Other recent observations have found around three high-confidence objects likely part of the Taurid stream, in line with our estimations.

How do you pick a project to work on?

How do you pick a project to work on?

When I first messaged Dr. Ye about research, I really was open to any sort of research in

the field of astronomy. I wanted to get some actual experience working in the field of astronomy before I

went to college, and being able to use real data in an ongoing project fascinated and excited

me.

How do you formulate a project for a student?

How do you formulate a project for a student?

That’s largely based on the interest of the student, what I feel the student might benefit from,

and what is available. When Jasmine reached out to me, I saw that she had experiences in

programming and statistical analyses, so I picked this project as it involved data processing

and statistics of survey science.

What is the number one quality you look at when you select a mentor to work with?

What is the number one quality you look at when you select a mentor to work with?

When I’m looking for a mentor, I want to find someone who I’m certain is willing to help me

through the process. I understand that I’m still relatively inexperienced compared to many

other students and Dr. Ye has been very patient and understanding. I’ve had a really good

experience, as I had the time to work through problems at my own pace and Dr. Ye was also

there to guide me when I had questions.

What is the number one quality you look at when you select a student to work with?

What is the number one quality you look at when you select a student to work with?

Dedication. And this was clear from Jasmine’s resume when she first reached out to me, so I

decided to work with her.

Was there a specific moment during the summer research work that was particularly exciting?

How about challenging?

Was there a specific moment during the summer research work that was particularly exciting?

How about challenging?

When we were searching through the streak database, we finally came across one candidate

that appeared to be an actual asteroid. Even though this asteroid was already discovered and

not likely part of the Taurid stream, it proved that our method worked. The initial excitement

from finally finding something was incredible!

A lot of this project also involved programming in Python, which I was not completely

comfortable with when we first started. Figuring out ways to solve problems and find the

asteroids we needed was initially very challenging for me, but slowly I started finding ways to

quickly sift through the large amounts of data we had.

Was there a specific moment during the summer research work that was particularly exciting?

How about challenging?

Was there a specific moment during the summer research work that was particularly exciting?

How about challenging?

Jasmine found an interesting target out of about 30,000 targets that, for a brief moment, we

thought that was the object we had been looking for. Even though it eventually turned out to

be something else, the excitement and the process of digging through it was memorable. We

also thought hard on how to interpret that object (along with the non-detection).

What do you think is the most valuable thing you learned this summer?

What do you think is the most valuable thing you learned this summer?

I think programming experience and writing skills I’ve learned are universally applicable to any

future project down the line. Right now, I’m studying engineering at CMU, though I want to

somehow incorporate astronomy into my studies later down the line. However, even if I

ultimately end up moving away from astronomy, the experience I’ve gained from my project

here is always going to come in handy whether it be another research project I conduct at

university, a job after graduation, or whatever else I may do later in my life.

What do you think is the most valuable thing you learned this summer?

What do you think is the most valuable thing you learned this summer?

It is really important for the mentor to recognize when to offer help and when to keep on the sidelines.

In science, answering one question also results in asking oneself a set of new ones. What are

these for you at the end of this project?

In science, answering one question also results in asking oneself a set of new ones. What are

these for you at the end of this project?

I want to know if in four, maybe five years down the line, what will I think of my work here?

This project was certainly an important milestone for me, as it is my first ever paper to be

published in a scientific journal. However, I’m curious as to what I will think of my own work

once I’ve gained more field experience down the line. I’m sure I’ll always treasure this project

and look back on it fondly, but I wonder how I’ll think about it critically in the future.

In science, answering one question also results in asking oneself a set of new ones. What are

these for you at the end of this project?

In science, answering one question also results in asking oneself a set of new ones. What are

these for you at the end of this project?

This project ends up with clear evidence that argues against a theory that was introduced in

the 1980s but was never unambiguously confirmed: we found that there were not that many

potentially hazardous objects in the Taurid swarm system that people once speculated there

might be. Now the question becomes: can we further quantify it? We have actually been

discussing with colleagues on how to take the project further, and that is pretty exciting!

The universe never fails to surprise us, but did you manage to surprise yourself this summer?

If yes, how?

The universe never fails to surprise us, but did you manage to surprise yourself this summer?

If yes, how?

When I first took on this project, I was honestly quite nervous. I felt like my programming

experience or general astronomy knowledge wasn’t initially enough to keep up with the tasks I

had to complete, but with all the help I got from my mentor, I was able to persevere through.

Another surprise was when I was conducting my search for asteroids, I got discouraged very

quickly; after looking through most of the data, I had not found any asteroids. However, at the

very end, it turned out that one of the streaks I was looking at had turned out to be one! Just

seeing any result at all was so exciting and made me feel that I had accomplished something

with all our work. I loved the feeling and I hope I can get excited over many more projects in

the future!