Friends of Palomar Observatory Website

Upcoming Events

The Newsletter of the Friends of Palomar Observatory, Vol. 15 No. 1 – May 2020

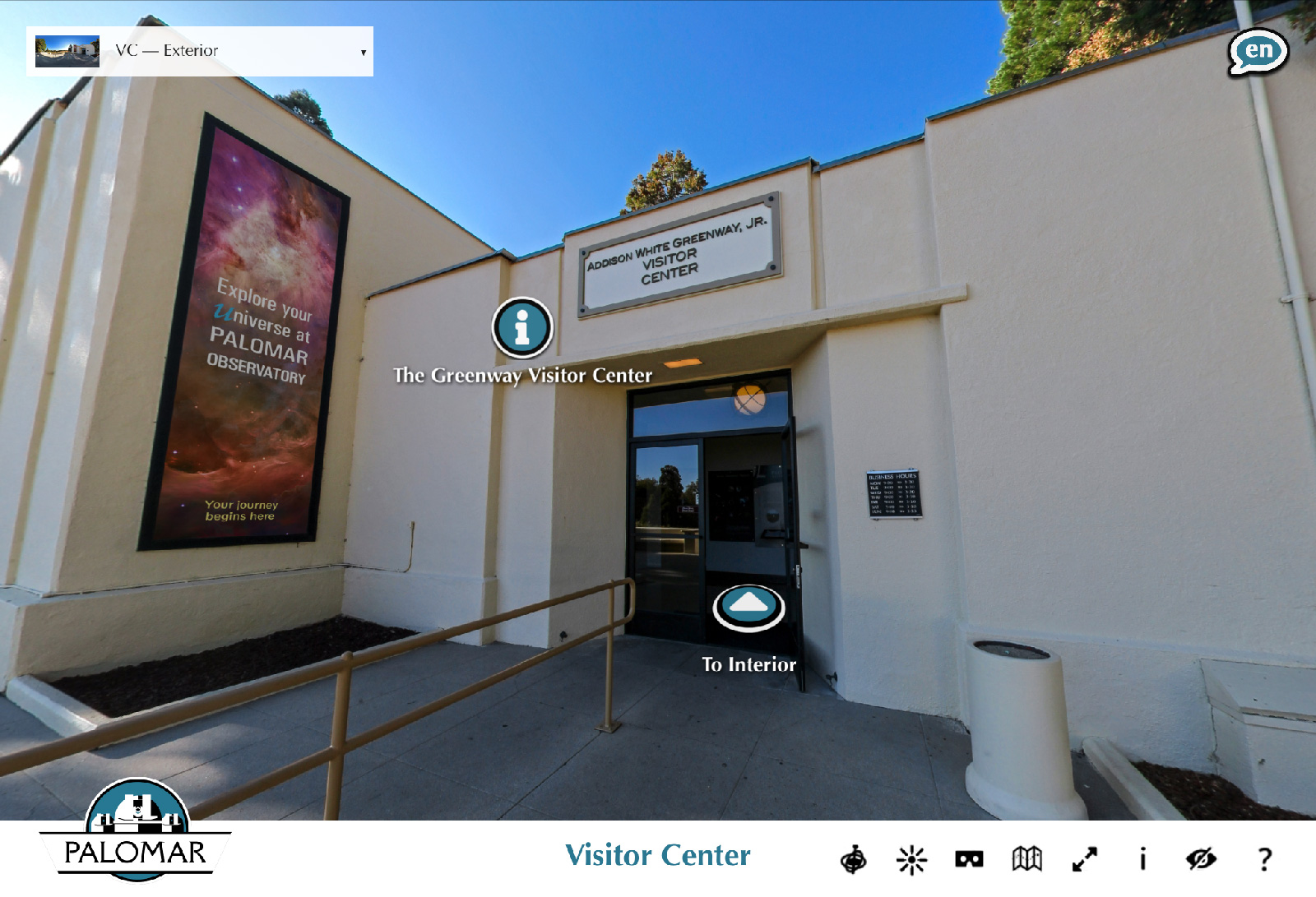

Palomar Observatory's New Virtual Tour

By Andy Boden

Welcome video to the new virtual tour. (Palomar Observatory/Caltech)

Gentle Readers,

Our hearts go out to all those who have experienced tragedy in our current circumstance, and in support and gratitude to all those who sacrifice to help keep ourselves and our loved ones safe. In this newsletter installment I will tell you about our own modest accommodations we are pursuing to address the profound disruption that the COVID-19 pandemic is in all our lives.

Writing this in mid-April the weather is turning beautiful in Southern California. We would ordinarily be excitedly starting our public tour season at Palomar Observatory; we are blessed to have so many supporters and enthusiasts in our Observatory community. But of course that isn’t happening yet: the Observatory is closed for the foreseeable future, operations are largely suspended, and hopefully all of us are as sheltered as we can be from the present pandemic-related tragedies. Under leadership from my longtime colleague Dr. Annie Mejía, the original plan had been to announce and roll-out new self-guided tour infrastructure at the Observatory for the 2020 tour season (I’ll have more to write on that in forthcoming newsletters), but our present closed circumstance makes that initiative for the moment moot.

As we are temporarily unable to receive visitors at Palomar, Annie and I decided our best alternative was to bring more of Palomar to you, our long-time friends, and potential Observatory enthusiasts near and far. I am happy to report that we have been able to redirect much of the self-guided tour development activity into a greatly augmented Palomar Observatory virtual tour, optimized for computer screens. Please find this virtual tour by following the accompanying launcher included in this article.

We have had a Palomar Observatory virtual tour for some time. Among the many upgrades in this expanded virtual tour for 2020 (not all available on mobile devices):

- More tour locations, including several inaccessible to the public (e.g. P48, P60, my personal favorite the top of the P200 Dome)

- Greatly enhanced context support (many new/revised text/info boxes and infographics, new “about this space” descriptions, and new media elements—video and narration—expanding on selected topics).

- Continued bilingual support for Spanish speakers

- Better navigation support including integration with Google Maps

- An illustrated help page

- A “lite” version taylored for smartphone screens

- More tour locations, including several inaccessible to the public (e.g. P48, P60, my personal favorite the top of the P200 Dome)

- Greatly enhanced context support (many new/revised text/info boxes and infographics, new “about this space” descriptions, and new media elements—video and narration—expanding on selected topics).

- Continued bilingual support for Spanish speakers

- Better navigation support including integration with Google Maps

- An illustrated help page

- A “lite” version taylored for smartphone screens

Annie and I have been working closely together during the COVID-19 sequestration to imagine and create this enhanced content; we hope you enjoy what we have added, and we would be excited to hear from you on what additional elements you think we should include in future virtual tour releases. I will take this opportunity to say what a fantastic job that Annie has done with these new materials—I know you will see and enjoy the results of her efforts in bringing more of the Observatory to our virtual visitors.

Of course no virtual tour can take the place of standing under the Hale and being surrounded by the passion and will and love that the telescope and its legacy represent. But until we can do that together again we hope this enhanced virtual tour will help keep us all mindful of what a special place Palomar is in our hearts.

With every wish for your safety and security and happiness in our troubled times,

-Andy

Max Mason: The Under Appreciated Hero of Palomar Observatory

By Steve Flanders

Charles Max Mason passed away in March 1961 at his home in Claremont, California. Shortly afterward, Caltech president Lee DuBridge wrote a tribute in which he celebrated Mason’s life of accomplishment and service. Dr. DuBridge took special note of the many contributions Mason had made to the building of Palomar Observatory:

The California Institute of Technology owes a great debt to Dr. Mason for the far-sighted, energetic and able way in which he directed the Palomar project…. It was his direction which kept the project on the rails, kept it within budget, and … kept it on schedule.[Quoted in Warren Weaver, “Max Mason, 1877-1961,” National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C., 1964, pp. 226-227.]

This statement raises two questions: first, in what ways did Max Mason contribute to the building of Palomar Observatory; and, second, why is his role not more widely recognized and celebrated?

In 1928, Caltech established the Observatory Council to administer the Rockefeller Foundation’s funds and to oversee all aspects of the 200-inch telescope project. George Ellery Hale had been appointed to chair the group and, in March 1936, he invited Mason to come to Caltech and join the Council in the position of vice chairman. Well aware of his own deteriorating physical condition, in doing this Hale was selecting his successor on the Council. In consequence, Mason assumed the leadership of the Council during periods of Hale’s incapacitation and was appointed its chairman when Hale died in 1938.

In 1936, Max Mason probably was the person best equipped to continue Hale’s leadership. Holding a Ph.D. in mathematics, he taught at the University of Wisconsin. A member of the National Academy of Sciences with experience in applied engineering, Mason commanded the respect and attention of Caltech’s scientists and engineers. In addition, he had worked closely with Hale during his term as president of the Rockefeller Foundation from 1929 to 1935. As a result, when he joined Caltech, Mason was readily accepted as a member of the team. He fit easily into his new role and, for the next dozen years, Mason gave the project his steady and competent leadership.

Technical, staffing and financial problems, a cascade of crises large and small—through it all, Mason solved or deflected one difficulty after another, always aware that any one of the problems appearing on his desk had the potential to derail the telescope’s construction. Working in the background, he kept an assortment of tasks on track, removing roadblocks often using only his personal persuasiveness. With a phone call or a memo or in a one-on-one meeting, he would reach accommodations, make agreements and acquire resources so that the project teams could continue moving forward.

To cite one example, sometime after the mirror’s arrival on the mountain, the first aluminization attempt failed because the pumps were not able to draw the high vacuum required. When he found out, Mason called upon his network of friends and colleagues. He spoke with Vannevar Bush who had been head of the U. S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) during World War II. Sometime later, an official at Oak Ridge, Tennessee appropriated two large diffusion pumps that were no longer needed by the Manhattan Project. Dispatched to Palomar, these pumps created a vacuum sufficient for the successful application of a thin coating of reflective aluminum to the mirror’s upper surface.

He did this quietly and in the background as a facilitator rather than as a front-line contributor. Nonetheless, on rare occasions, Mason turned his hands to the work. Dr. DuBridge tells of one such incident in which Mason performed a set of calculations to model the way the mirror would deform under its own weight as the telescope tracked the sky. His work enabled a later redesign of the mirror supports that resulted in the elimination of virtually all astigmatism in the telescope’s field of view.

While these two events were recorded, mostly the details of Mason’s work went unnoticed by all but a few close associates. He did not generate drama and he did not try to gain the public’s attention.

Yet, beyond these two examples, it is clear that, during his 13-year term as leader of the project, Mason also managed and resolved a number of larger and more visible problems that rose to threaten the telescope’s success. As Dr. DuBridge suggests, Mason kept the project’s finances under control even after the loss of one-tenth of the budget in the failed fused quartz effort at General Electric Company. When the discovery of fractures in the upper layers of the 200-inch disc set off a crisis just weeks after he joined the Observatory Council, Mason urged patience and caution and for almost two years relied upon the expertise of George McCauley at Corning until the cracks disappeared in the lower layers as McCauley had predicted. In another instance, Mason removed Clyde “Sandy” McDowell, the project’s construction planner and coordinator, as McDowell’s deteriorating relations with the scientists and engineers rose to threaten the stability of the project.

Looking at this partial listing of Mason’s many accomplishments and contributions, Lee DuBridge’s phrase about keeping “the project on the rails” is telling. From one crisis to the next, Mason would push and cajole and persuade, applying sufficient pressure where needed to keep the work on track in accordance with Hale’s plan. Taken all together, it is part of his greatest contribution to Palomar Observatory: Max Mason overcame all the issues that had threatened to derail the work and brought the building of the Hale Telescope to a successful conclusion.

Even so, the account given thus far—the story of Mason’s work to manage the development phase of the project—represents only a portion of a larger story. To be complete, this discussion must also describe the greater difficulties Mason encountered as he confronted issues that could not be ignored even though their consequences might not be apparent until after the start of operations.

The grant of the International Education Board of the Rockefeller Foundation vested ownership of the telescope with Caltech and gave responsibility for its successful construction to the Observatory Council. But the grant provided no funds for the telescope’s later operations. Even so, Mason was aware that the Council necessarily had a responsibility, if only implied, to look beyond the building phase to the telescope’s long term operations. He knew that the investments made by the Rockefeller Foundation would be seen as failures if the finished telescope were unable to open due to lack of operating funds.

John Anderson, Clyde McDowell, Max Mason, and Russell Porter at Palomar, 11 November 1936. (Caltech Archives)

In 1938, as he assumed chairmanship of the Council, Mason was also aware that Caltech had no money to fund operations, had no staff with experience running large telescopes, and on campus a physics faculty not yet prepared to design and execute a world-class program of research in astronomy and astrophysics. Confronting these three problems, Mason and others on the Council realized that soon they would be forced to confront these funding and organizational issues.

It would, however, likely be a complex and contentious confrontation because the grant had left a second unresolved issue: no provision had been made for the establishment of an organization that would manage the telescope’s operations and finances. The complexity in this problem lay in the fact that the terms of the grant required Caltech to allow experts and scientists working at Mt. Wilson Observatory to participate in the project, people who were employees of the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Because the Carnegie Institution wanted control of the telescope as badly as Caltech did and because no management structure had been agreed upon and because the Carnegie Institution possessed all of the financial and other resources that Caltech lacked, dangerous conflicts were deemed unavoidable.

And just such a conflict began to unfold in May 1938 when Vannevar Bush of MIT accepted an appointment to become president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. For its part, Caltech had its share of people—the trustee Robert Millikan among them—ready to defend the Institute’s rights and ready as well to battle to maintain Caltech’s control of the world’s most famous and prestigious instrument of science. However, by comparison, Bush was a true partisan fighter determined to advance the interests of the Carnegie Institution by whatever means. He was convinced that, in gaining control of the 200-inch telescope, he would move the Carnegie Institution one step closer to its goal of becoming the nation’s premier center for research and graduate training in engineering and the physical sciences.

Unfortunately, Millikan and others were working toward exactly the same goal but in their case for Caltech rather than for the Carnegie Institution. The inevitable collision greatly complicated Max Mason’s problem, originally a concern for the telescope’s future operating budget that suddenly threatened to become a clash of institutions. It was an ominous prospect because the coming contest would be fueled as much by a collection of long-standing organizational resentments as by the conflicting ambitions of its chief antagonists. Most worryingly, however, such a clash might leave Mason standing in the middle facing the battle exposed and without cover.

It was at this point that Mason made a contribution to Palomar Observatory greater than all the accomplishments described in the first half of this story. He managed the dangers that developed during the ensuing fight for control and, by navigating a dense web of individual resentments, long-standing distrusts, technical crises, vested interests, and institutional turf battles, he successfully brought the 200-inch telescope project to the end of its construction phase and ready to begin operations with the Observatory having a sound management structure and a way to pay its bills.

How did he do this? Seen at a distance, two items stand out. First, before the war, Mason worked to build trust and form relationships. He never descended into partisan bickering but rather focused upon the completion of the telescope. There were no hidden agendas and, when they held negotiations, Bush responded to Mason’s straight forward approach by agreeing to a series of large and small compromises. Both of them had come to understand that neither organization was capable of managing the telescope alone and that an agreement for its joint operation must be reached. With that, Mason and Bush might actually have come to such an agreement in late 1940 had not the urgency of his new job in Washington forced Bush to put further discussions on hold.

And the second point to be made here relates to the circumstances of the job Bush held during the war. He had spent five years overseeing massive projects funded by the federal government in pursuit of the goal of national defense. When he came out of this experience, his institutional focus and partisan outlook were gone. Gone too was his idea that institutions should set up advanced research programs in ways that would promote their own interests.

In their place, Bush had come to believe that science represented a national enterprise and that research, now for the first time substantially supported with public money, must reflect national priorities. In 1945, Mason was able to leverage this remarkable transformation. Bush no longer insisted that the 200-inch telescope be put under the control of Carnegie’s staff at Mt. Wilson. Instead, he was willing to split the difference: Mt. Wilson would be controlled and funded by the Carnegie Institution while Palomar Observatory would be managed by Caltech, an organization now greatly expanded during the war and better positioned to fund operations and to establish a world-class program of research and training in astronomy and astrophysics.

With this roadblock removed, in late 1945 Bush and Mason published a plan for the joint operation and unified science program of the two observatories. Subsequently ratified by the trustees of Caltech and the Carnegie Institution, the agreement created a new organization, the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories. Operations began on April 1, 1948.

Even so, Mason and Bush had arrived at their 1945 agreement with the understanding that Walter Adams, Hale’s successor as director at Mt. Wilson, was about to retire. They were anxious to see that a new director assume office before joint operations began in 1948. Under the agreement, Bush was authorized to select the new incumbent. What he did set a new precedent and startled many. While he considered certain obvious choices, Edwin Hubble and Harlow Shapley among them, he instead chose as director Ira Bowen, a well-respected spectroscopist and member of the physics faculty at Caltech.

Caltech president Lee A. DuBridge formally dedicates Palomar Observatory and names the 200-inch the Hale Telescope on June 3, 1948. Other speakers included Max Mason, chairman of the Observatory Council (second from the right); Raymond B. Fosdick, president of the Rockefeller Foundation; Vannevar Bush, president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington; Ira S. Bowen, Director of Mt. Wilson and Palomar Observatories; and James R. Page, chairman of the Caltech Board of Trustees. Also on the speakers' stand are Walter S. Adams, Director Emeritus of the Mount Wilson Observatory and member of the Palomar Observatory Council, and Mrs. Evelina Hale. (Palomar/Caltech)

In making this selection, Bush demonstrated and acted upon the transformations that had taken place in his ideas about science and its institutions. As many of his colleagues were reaching similar conclusions, he had put aside his outdated parochial notions regarding the role of institutions. The new narrative demanded that the institutions of scientific training and scientific research equally serve the common needs for defense, security and economic growth. The experts were now in charge, efficiency and productivity were now the highest values. It was a new era in which the old institutional rivalries accounted for little. From now on, American science would find its best accommodations and recruit its best practitioners not at the old philanthropic institutions but rather at places like Caltech.

Through all of this, the nature of Mason’s contribution is clear: He managed the Observatory’s transition out of its development phase and, under a new organizational plan, made it ready for the start of operations. However, this accomplishment is all the more impressive because the transition he engineered had two larger dimensions. First, Mason guided the telescope project through changes brought on by World War II in which the nineteenth century foundations of “big science” were replaced by an enormous federal bureaucracy that did away with the handshakes and gentlemanly agreements of Hale’s era and in the process recreated “big science” at levels George Elley Hale could never have anticipated.

Second, between the beginning of his tenure in 1936 and his retirement from the reconstituted Observatory Committee in 1949, Mason drove the telescope’s planning and construction through a boundary zone in the history of the Institute. Judith Goodstein, Caltech’s University Archivist Emeritus, has written about this period:

Caltech’s history is divided into two distinct eras. The first Caltech era was created by Hale, Millikan and [Arthur] Noyes. Thirty years later, after World War II, the physicists Lee Alvin DuBridge and Robert Bacher did the job all over again.[Judith Goodstein, “History of Caltech,” The Nobel Prize, accessed 4/9/2020]

Science operations began on the Hale Telescope in November 1949 and the Caltech astronomers who used it were members of a research and educational institution that had lost its “old-guard.” Now run by a new generation of scientists and engineers, Max Mason guided the telescope project through this transition, managing change and providing continuity. At the same time, he proved himself to be as much an agent of change as a manager of change. It was Mason who convinced Lee DuBridge to accept Caltech’s offer to become the Institute’s new president, a change and renewal of leadership that set in motion a decades long process of growth and diversification.

Finally, with such a long list of contributions and given the essential role he played, why is Max Mason so often overlooked in discussions of the Observatory’s history?

The answer to this question is linked to a theme that has recurred frequently in this discussion. From the outset, Mason preferred to work in the background without fanfare and the glare of bright lights. Perhaps, the central problem is this: Starting in 1936, Mason stepped into Hale’s job, not into his role. Hale had been the public face of the project. When he chose, Hale was able persuasively to address the literate public. As the project’s founder and chief visionary, Hale could speak with authority and he could lead with unquestioned legitimacy.

Coming into the job, Mason had none of this. He could not possibly have replicated Hale’s stature and he knew better than to try and trade on Hale’s legitimacy. Mason had his own form of legitimacy, apparent to his associates but invisible to members of the public. By the nature of the institutional setting, Mason would always have a less visible though no less important role. He rarely if ever addressed the mass media and never sought to speak to the public as Hale had done.

Mason, therefore, may best be seen as a scientist who spoke to other scientists. He enabled the work going on at Palomar and in Pasadena by quietly solving the problems that hampered the work of others.

As he saw it, Mason’s task then was to implement and complete what George Hale had started. He did not seek any greater notoriety and for this reason his contributions have always seemed pale when compared to those of his predecessor. But it is not merely that Mason’s contributions pale in comparison, rather it is that his contributions are obscure and often difficult to describe. In his work, Mason generated little drama and left no pithy anecdotes to enliven later discussions of Palomar history.

But the style and methods he adopted were well suited to his situation and to the success he achieved in building Palomar Observatory.

Even so, Hale’s departure left what might now be called a “celebrity gap.” While Mason had no interest in filling this void, others were eager for the attention. A best selling book profiled some of the people working on the project. Certain people published articles in the popular press. Images of several of the astronomers appeared on the covers of Time and Life magazines. Intolerant of all this noise, Mason was nonetheless overwhelmed by it and, because he offered nothing the press was particularly interested in, he disappeared from sight probably much to his great relief.

For all these reasons, Mason’s contributions to Palomar Observatory have gone unrecognized and under-appreciated. A competent administrator and an esteemed scientist, he was 71 years old when the Hale Telescope was dedicated in 1948. He had come to complete one task and now, with no further role to play at Caltech, he made his exit.

With Ira Bowen in charge and with the telescope about to enter service, Mason and his wife moved to Claremont, California where he began teaching at Claremont Men’s (now Claremont McKenna) College. In his 1964 biographical commemoration, Warren Weaver tells a story that, whether true or merely apocryphal, nicely summarizes the concept Mason relied upon to motivate people in organizations, what Weaver calls “one of Max’s favorite ideas:”

He gave a course of lectures on “general science” to a good-sized group of undergraduate men and women. On the occasion of the first lecture someone had put a vase of flowers on the speaker’s table. After entering the room, Max took a flower out of the vase and remarked casually, “I’ve heard that flowers fade more slowly if you put an aspirin tablet in the water. Is that true?” After this remark he left the room [and] that was the whole of the first lecture.[Warren Weaver, “Max Mason, 1877-1961, A Biographical Memoir,” The National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D. C., 1964, p 230.]

COVID-19 Response

By Andy Boden

Like almost all facets of our lives, Palomar Observatory has been forced to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by radically restructuring its operations. Since late February it had been clear that action would be required to protect staff and public safety during the emerging health crisis. Observatory management began meeting to discuss possible actions on 28 February, and on 18 March we executed our "phase 4" action to suspend Hale Telescope operations. That operations suspension remains our present status.

Happily, I can report that our smaller telescopes (the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope and the 60-inch telescope) operate robotically, and we have been continuing science operations with them. As in our typical operational model, nighttime robotic operations with P48 and P60 are being monitored by our Hale Telescope operators (TOs), but now from the comfort of their couch rather than the Hale data room! I worry that once the TOs get used to monitoring the telescopes from home...

Thankfully our entire observatory staff report that they are all healthy and safe and sheltering in place. I similarly hope all of you read this note well and sheltered and provisioned.

Of course I share your regret in forgoing discovery opportunities during this operations suspension. But the present crisis will pass, and the observatory will return to operations and its typical high productivity as soon as it is safe and practical to do so. We are imagining what returning to operations might look like, and circumstances where we might be able to do so without risk to observatory personnel. We will continue to monitor the evolving situation and keep you informed of our plans to resume science operations with the Hale at Palomar Observatory.

Upcoming Events

On 16 May 2020 at 11am, Palomar's Deputy Director Dr. Andy Boden will be making a Zoom presentation titled “Astronomical Interferometry and you (and Palomar).” I’ll send out the Zoom link to all the FOPO members shortly before the start of the presentation. Below is the abstract of the talk:

In addition to the year of global pandemic, 2020 is the centennial anniversary for the first measurements of apparent stellar diameters beyond the Sun, using a special purpose interferometric "boom" on the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mt. Wilson. From there astronomical interferometric techniques blossomed episodically in optical, infrared, and radio wavelengths, and have been impactful in fields as diverse as star and planet formation and stellar astrophysics, to active galactic nucleii and super-massive black holes, and gravitational wave detection.

In this talk, Dr. Boden will be telling you a story on several levels: in general how astronomical interferometry is a method utilizing our understanding of "light" to open certain windows on the universe that would otherwise be closed to us; the role that interferometry played in the Mt. Wilson and Palomar creation story and history; to the role that interferometry played in his own personal journey to Palomar Observatory. He hopes to leave you with a richer understanding of astronomical methods and the fundamental unity of measurements made with both filled aperture and "sparse" aperture methods.

If you have questions or are unsure how the remote presentation will work, please email me before the meeting and I’ll do what I can to help.

We intend to schedule other FOPO events later in the coming months.

- Steve Flanders

Questions? We've answered many common visiting, media, and academic questions in our public FAQ page.

Please share your feedback on this page at the

COO Feedback portal.

Big Eye 15-1

Last updated: 7 May 2020 AFB/SBF/ACM