The K2 Mission

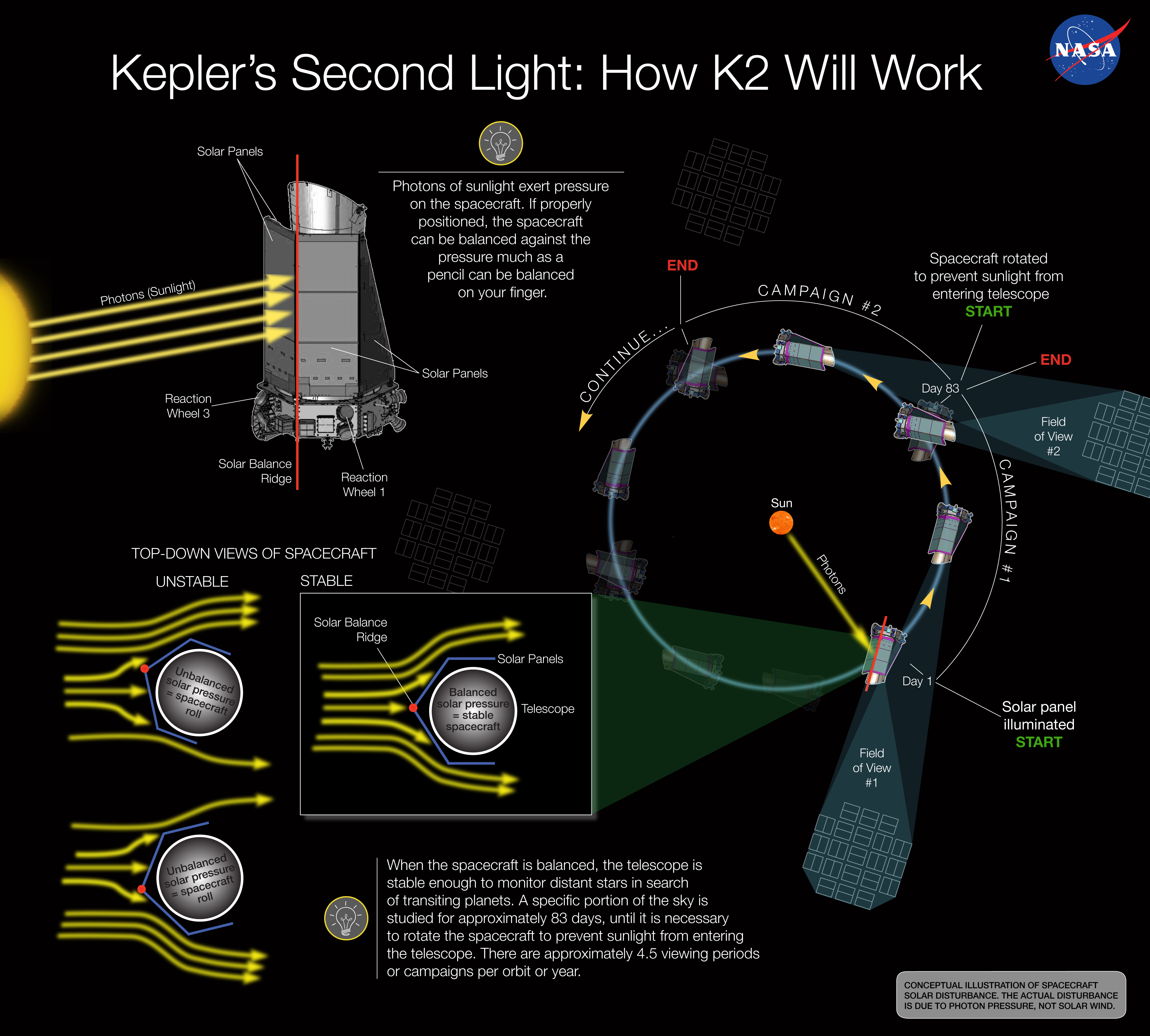

After the failure of two of its four reaction wheels (used to dump angular momentum) in 2013, the Kepler spacecraft could no longer maintain the pointing stability required for its nominal mission: quantifying the occurrence rate of Earth analogs in the Galaxy. Thanks to the novel strategy developed by NASA engineers, the mission did not end there. The telescope is now surveying the ecliptic where solar radiation pressure can help maintain stable pointing (see below). Every 3 months, the telescope observes a different field of view, providing a fresh sample of bright stars for transiting planet discoveries. I will showcase a few exciting planetary systems that we discovered using K2.

K2-22b

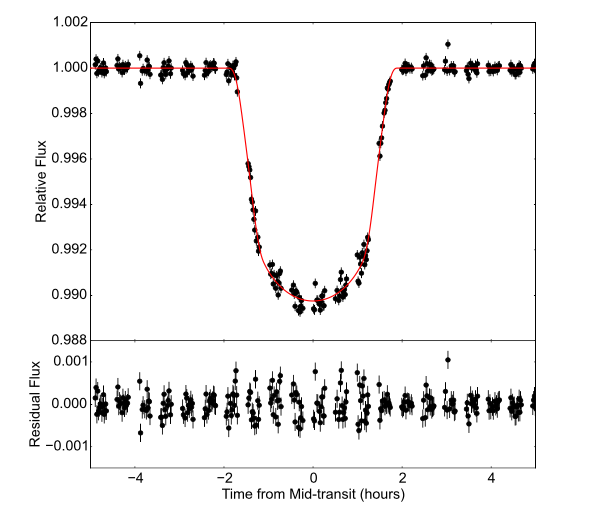

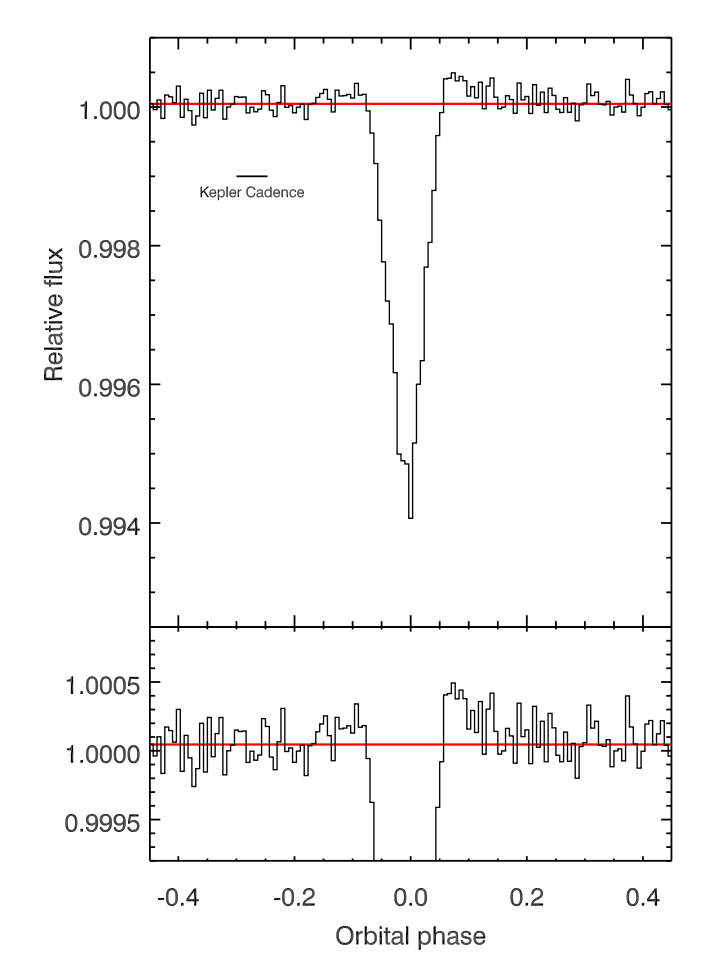

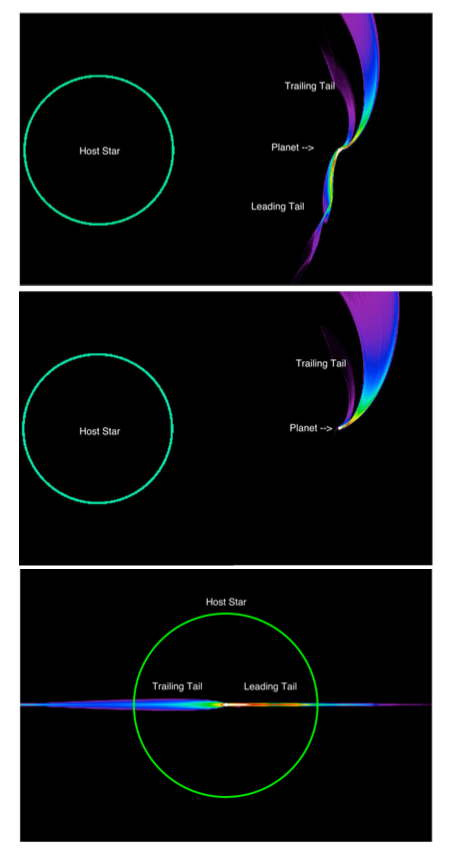

K2-22b orbits a M-dwarf every 9.1 hours. The observed transit depth is highly variable (0% ~ 1.3%) and wavelength-dependent. A closer look at the transit profile reveals flux bumps just before and after the transit. These bumps may be caused by dusty tails escaping the planet’s Hill sphere. K2-22b is likely disintegrating or emitting dusty effluents quite similar to KIC 12557548 and KOI-2700b. Read More.

GJ 9827 (K2-135)

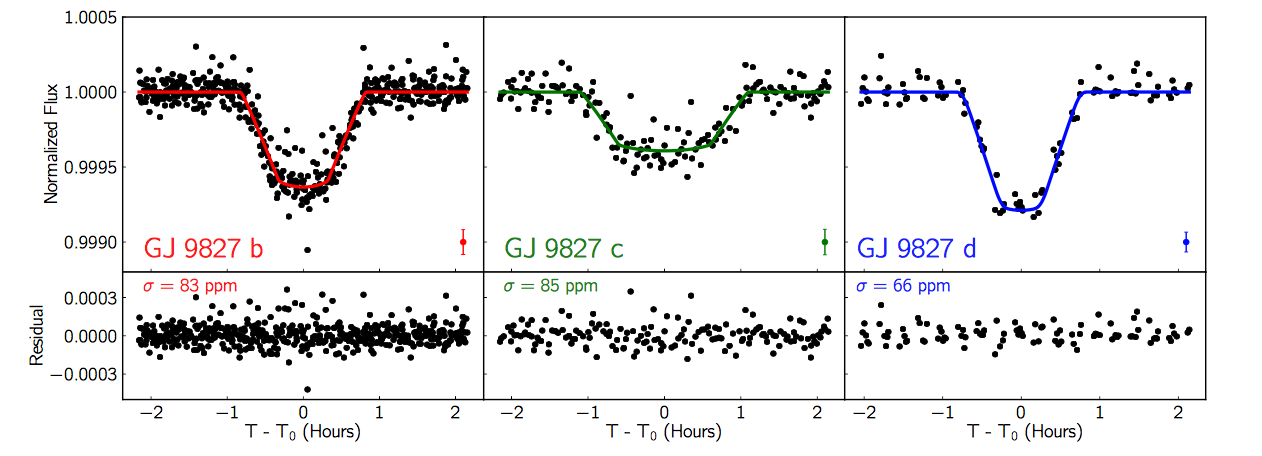

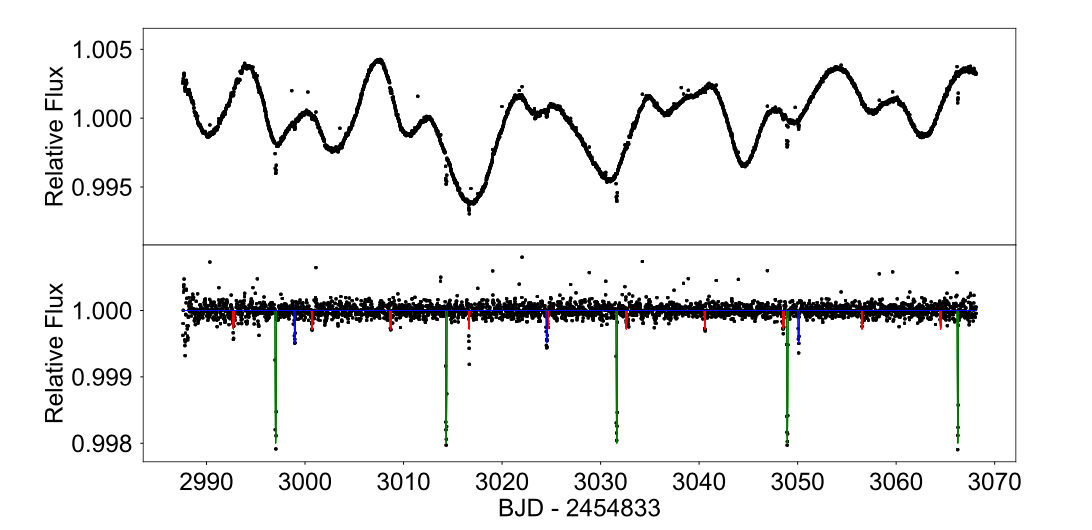

GJ 9827 is a nearby (30pc) bright (V=10.4) K star. We discovered three transiting planets with radii between 1.4 and 2.1 R⊕ and orbital periods between 1.2 and 6 days near a 1:3:5 mean-motion resonance. With such a bright and small host star, the system is one of most favorable targets for atmospheric characterization using the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The sizes of planets staddle the previously identified rocky-volatile transition at 1.6 R⊕ where smaller planets most likely have rocky compositions while larger planets tend to have Hydrogen/Helium or other volatile envelopes. Figuring out the compositions of all three planets in this system is particularly interesting for comparative planetology. Read More.

K2-136

K2-136 is a K dwarf in the Hyades cluster. This is the first planetary system in an open cluster with multiple transiting planets: the three transiting planets have radii between 1.1 and 3.1 R⊕ and orbital periods between 8 and 25 days. The orbital configuration and the composition of planets evolve over time under the influence of tides, dynamical interaction, atmospheric escape and other processes. Therefore it is instructive to study the distribution of planetary systems as a function of age. However, well-measured stellar ages are hard to come by for field stars. On the other hand, stars in open clusters are believed to be born in the same chemical environment with similar ages. With an age of 600-800 Myr, the planets of K2-136 may be still undergoing processes such as photoevaporation, a claim future follow-up observation may confirm. Read More.

EPIC 219388192b (CWW 89Ab)

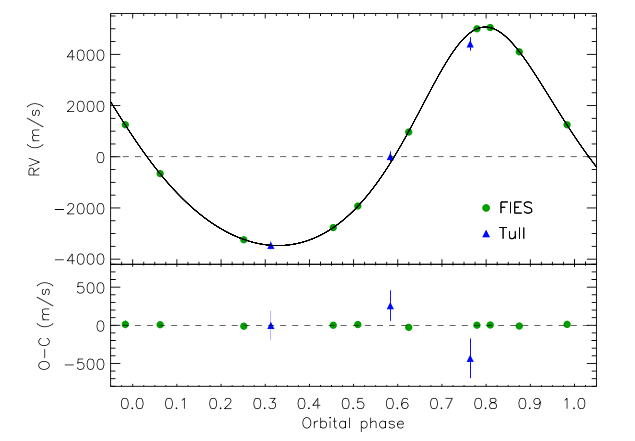

EPIC 219388192b is a brown dwarf (36 Jupiter mass) transiting a G dwarf in the open cluster Ruprecht 147. With an orbital period of 5 days, EPIC 219388192b is an inhabitant of the so-called Brown Dwarf desert: a paucity of brown dwarves with close-in orbits. With the help of ground-based follow-up observation, we pinned down the radius, mass and eccentricity of EPIC 219388192b to high precision. Given the cluster membership, the age is also well-constrained to about 3 Gyr. The Spitzer follow-up observation by Beatty et al indicated that EPIC 219388192b is over-luminous for its age. A possible explanation is temperature inversion of the atmosphere. The thermal inversion may stem from a high C/O ratio that would favor a core-accretion formation scenario. Read More.