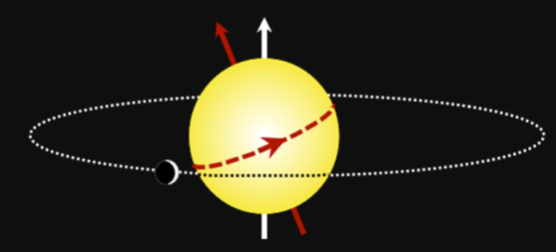

What is the stellar obliquity of a planet?

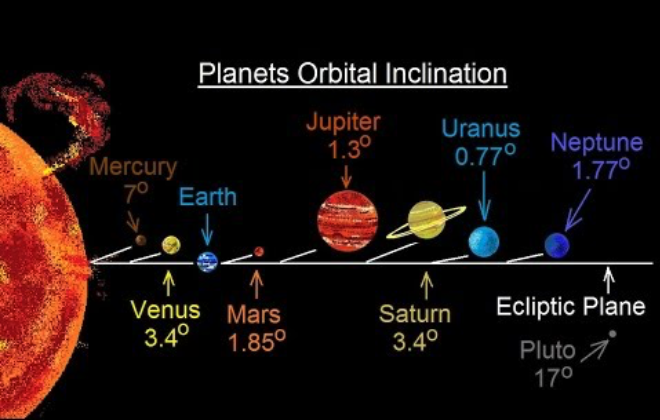

The tilt of a planet’s orbit is measured with the stellar obliquity which is the angle between the orbital axis of a planet and the rotation axis of its host star. In our solar systems, the planets are really coplanar, with the obliquities generally below a few degrees. It was this coplanar configuration that inspired early ideas about planet formation in disks.

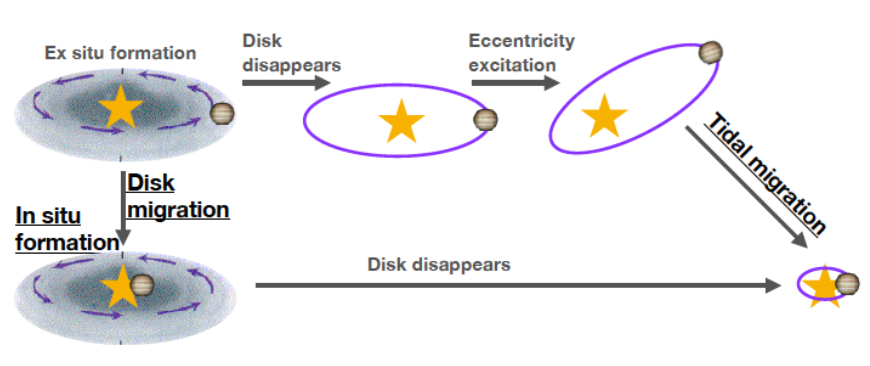

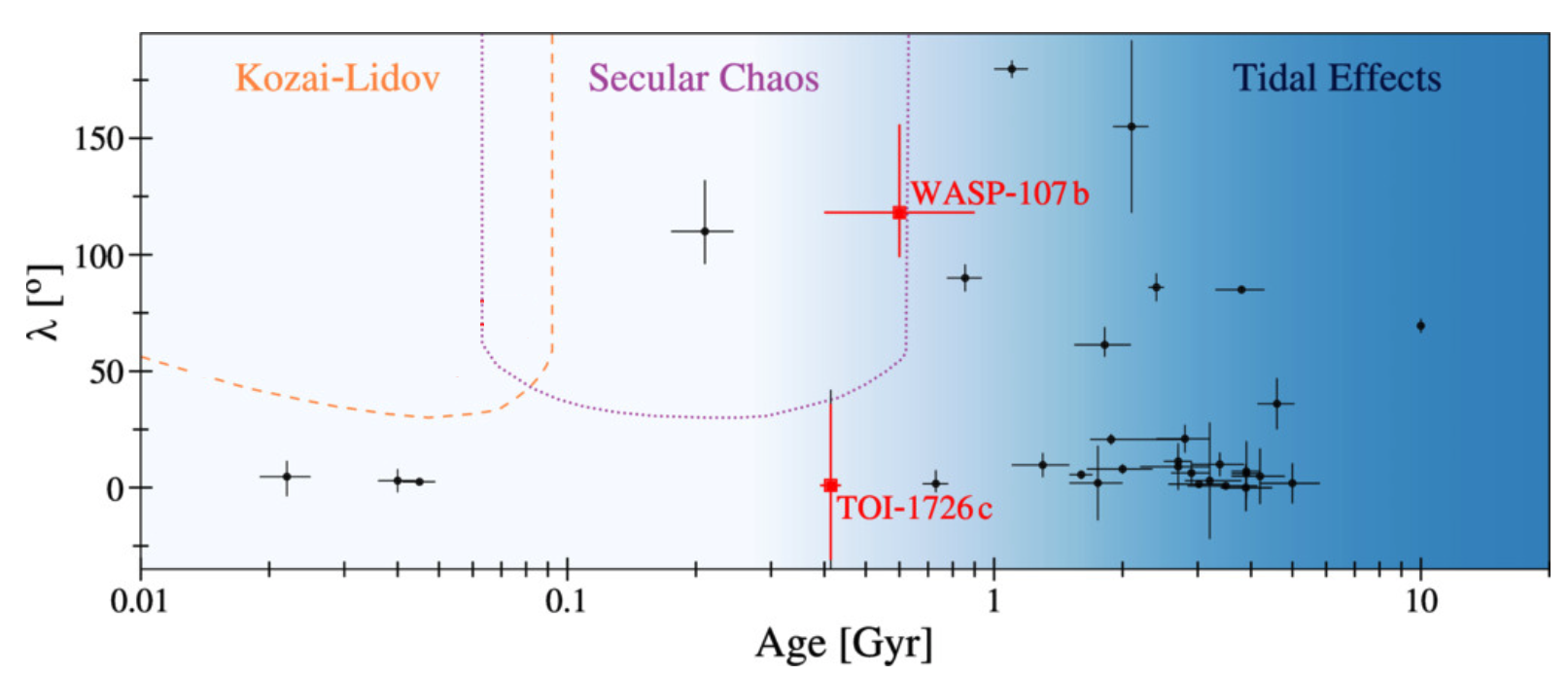

However, many exoplanets are on perpendicular or even retrograde orbit around their host star. The high obliquity has been interpreted as a sign of high eccentricity migration, in which case the planets initially formed further out in the disk, before some dynamical process excites the planet onto an eccentric, inclined orbit. Tidal interaction with host at the periastron shrinks the orbit, but the high inclination persist for much longer since it is damped by tides raised on the host star which is generally much less dissipative.

Why are some planets on oblique orbits?

Many theories have been proposed to explain tilted planetary orbits. Crucially, many of these theories operate on very different timescales. Some tilt the planetary orbits when the protoplanetary disk is still present (disk warping, stellar fly-by). The famous Kozai-Lidov mechanism typically operates over 10 kyr to 100 of Myr depending on the system configurations. On the other hand, the secular interaction between planets typically shows its effect after hundreds of Myr. For even older stars, tidal interaction with the host star begins to take effect, and it tends to realign a misaligned planet. Obliquity measurements of young stars with well-known ages, particularly those in young clusters, will be instrumental for identifying the dominant dynamical process at play in planetary systems. Our recent works (Dai et al. 2020 and Rubenzahl, Dai et al. 2021) added important points to the stellar-obliquity diagram.

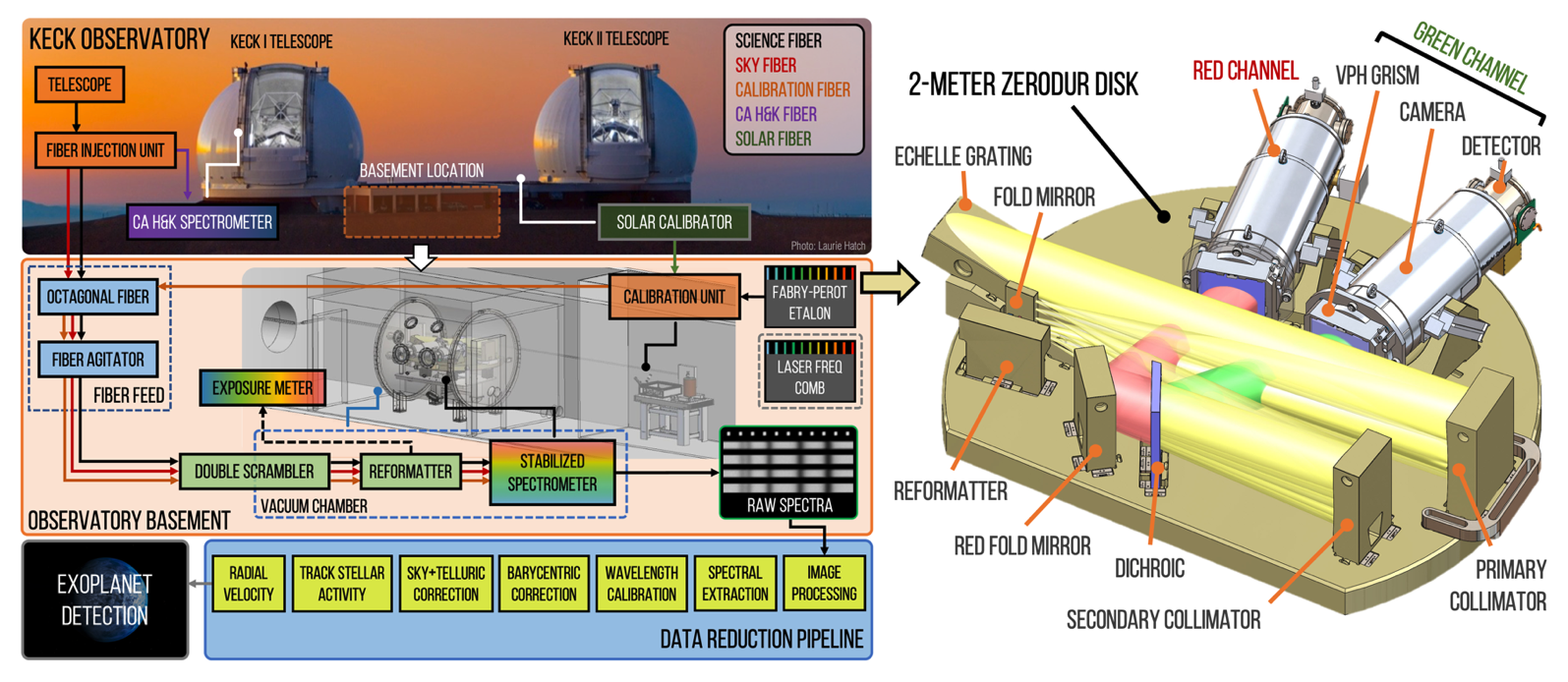

The Keck Planet Finder

The Keck Planet Finder or KPF (PI: Prof. Andrew Howard) is the next generation spectrograph for the Keck Observatory. It will see first light next summer. KPF use the latest technology such as double-scrambling fibers and Zerodur glass optical platform which has an exceptionally low thermal expansion coefficient. KPF covers the wavelength range of 445--870nm with a resolving power of 95,000 and a designed noise floor of 0.3 m/s.I am leading the Stellar Obliquity Program for KPF. KPF’s unique combination of 10m aperture, high throughput, and high stability will push the limit of obliquity measurements to fainter, scientifically more illuminating star. We are particularly interested in expanding stellar obliquity measurements to younger planetary systems discovered by the TESS mission.