A Tension Between Disk Migration and Observed Planetary Systems

A key prediction of modern planet formation theory is that planets migrate as they form in a protoplanetary disk (e.g. Kley & Nelson 2012). This is due to the tidal interaction between the planet and the disk. In most part of the disk, the net effect is migration towards the central star.

If multiple planets are forming simultaneously, they may undergo differential migration and get locked into a state of "mean-motion resonances" (MMR). MMR happens when the planets orbital periods are close to some small integer ratio. In resonance, their mutual gravitational perturbation phase up and accumulate over multiple orbits. The resonant interaction effectively acts as a potential well that traps planets in resonance while both are moving towards the central star, see the following video (Credit: Mills):

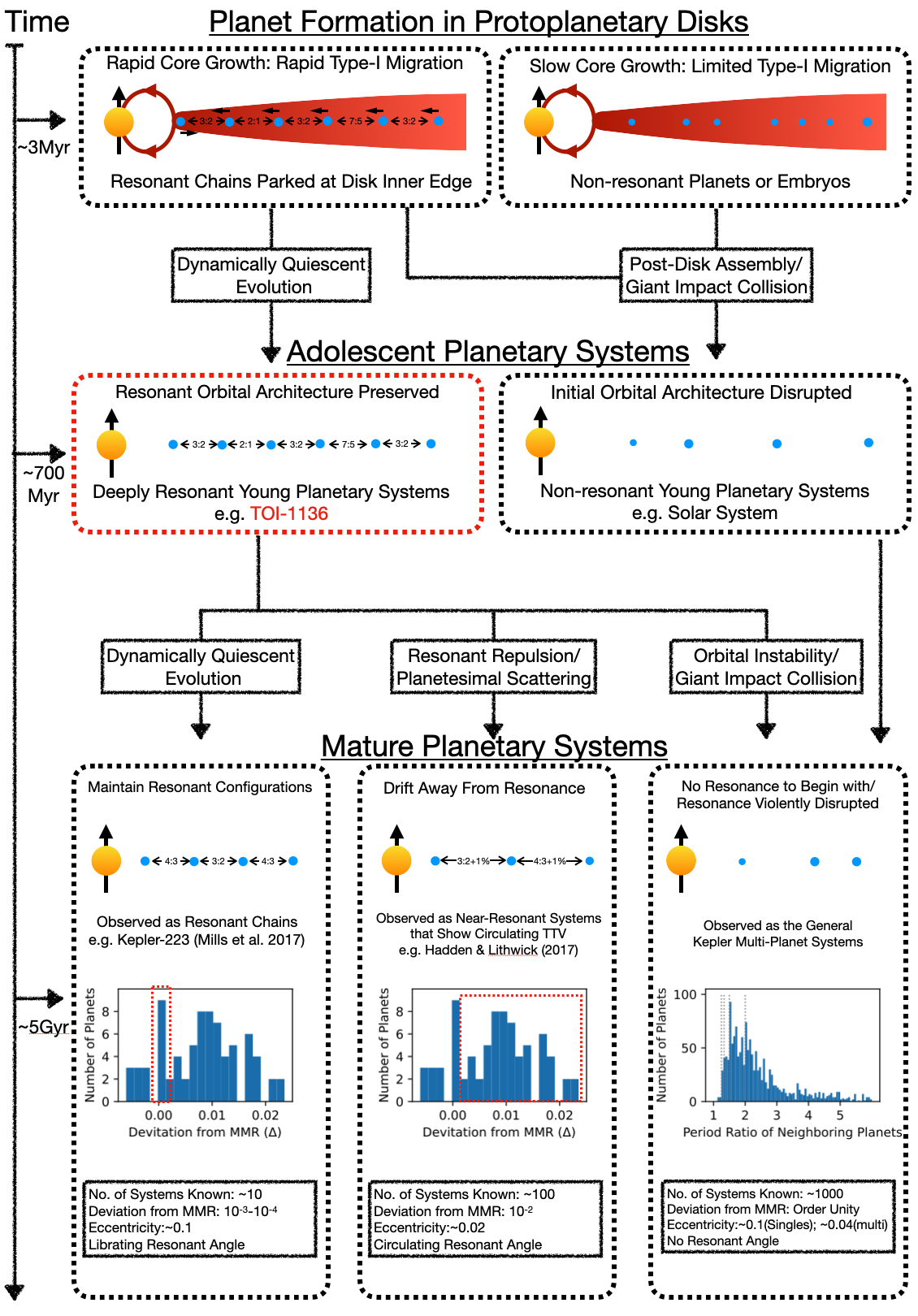

There is a tension between disk migration simulations and the observed multi-planet systems. The migration simulations consistently produced an abundance of planetary systems locked in a chain of resonance. However, resonant chains only represent a small fraction of the observed planetary systems ( Fabrycky & Winn 2015). The vast majority of Kepler and TESS multi-planet systems are non-resonant. Our Solar System also lack resonances among the planets, although the inner three Galilean moons are in a Laplace Resonance.

A Deeply-Resonant, Young Planetary System Produced by Disk Migration

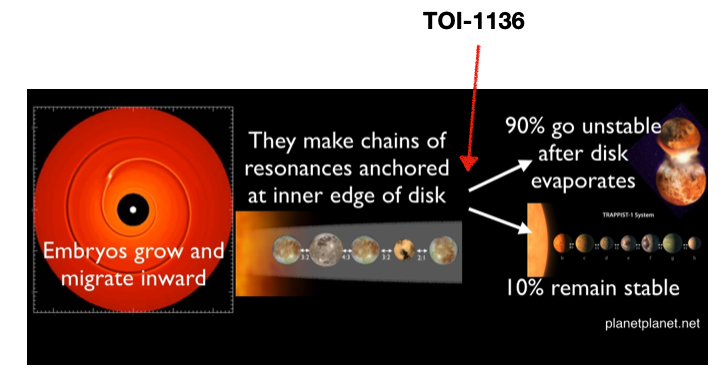

Previous works invoked a combination of planetesimal scattering, resonant repulsion, and orbital instability to break the initial resonant configuration produced by disk migration. These dynamic evolution may take Gyr to manifest. Our recent discovery of TOI-1136, a young (700-Myr-old), 6-planet system, provides a crucial missing link to this picture ( Dai et al. 2022).

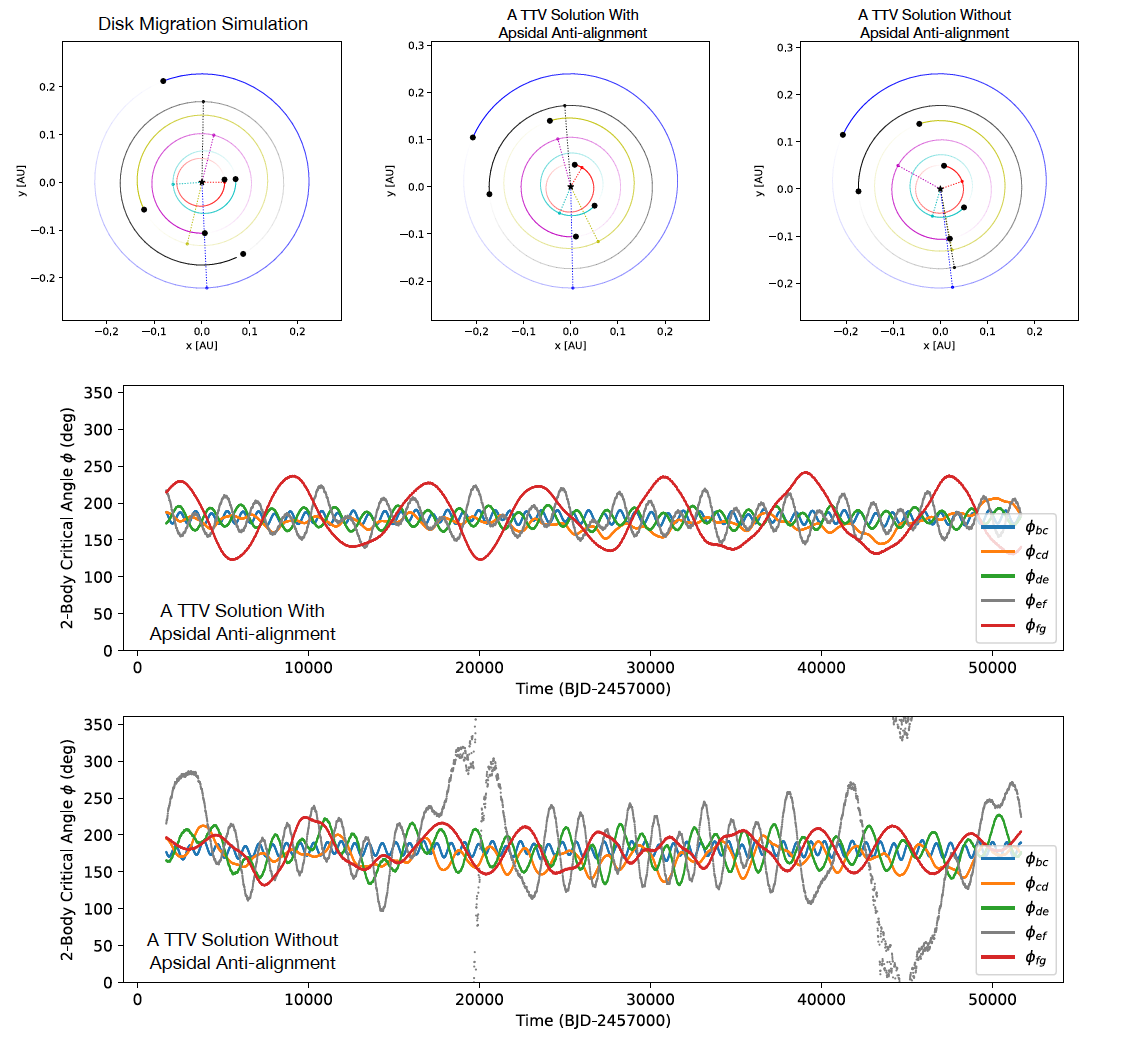

TOI-1136 is a young G star hosting at least 6 transiting planets between 2 and 5 R⊕. The orbital period ratios deviate from exact commensurability by only 10^−4, much smaller than the 10^−2 deviations seen in typical Kepler near-resonant systems. By carefully analyzing the transit timing variations, we demonstrated that the planets in TOI-1136 are in true resonances with librating resonant angles.

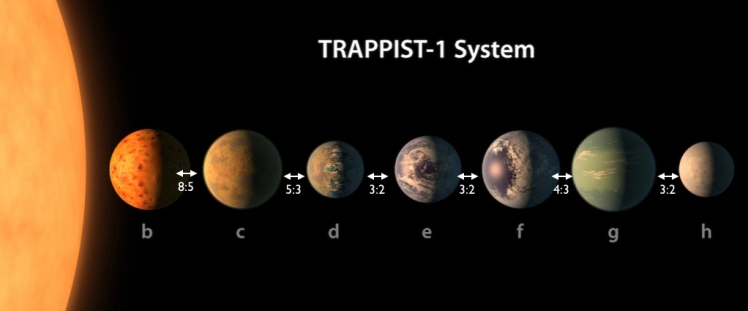

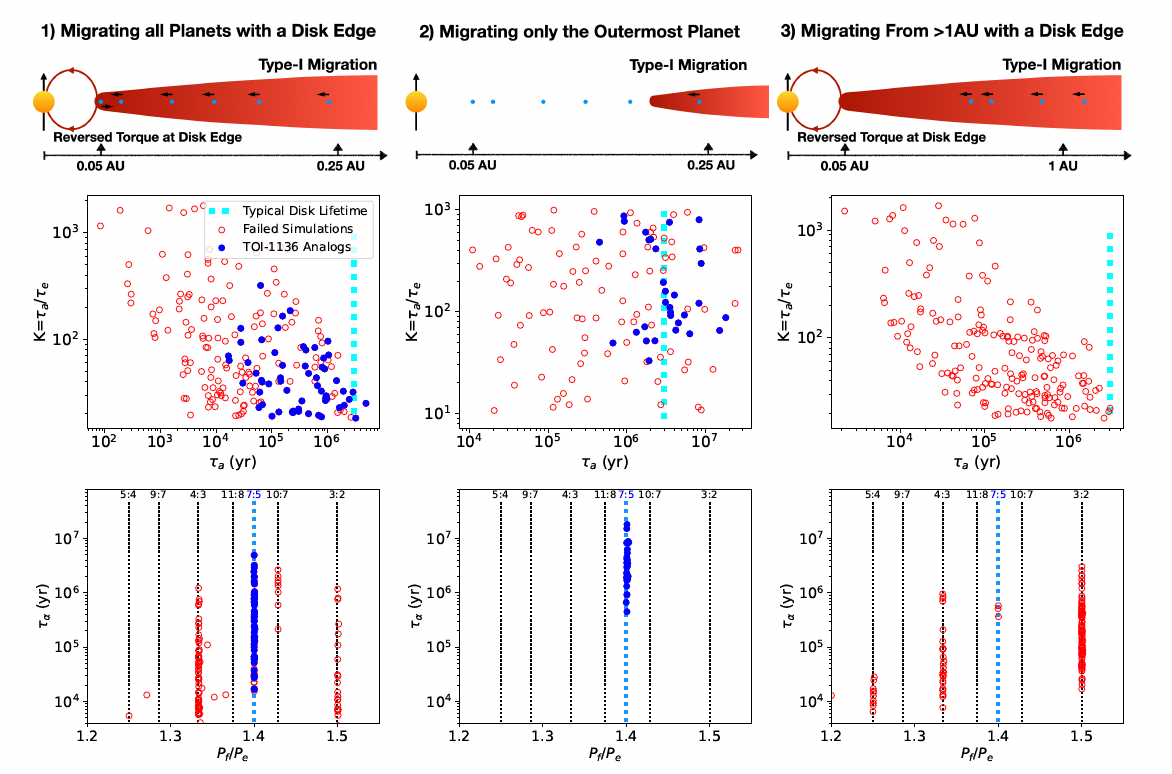

With period ratios near 3:2, 2:1, 3:2, 7:5, and 3:2, TOI-1136 is the first known resonant chain involving a second-order MMR (7:5) between two first-order MMR. The formation of the delicate 7:5 resonance places strong constraints on the system’s migration history. Second-order resonance is much weaker than first-order resonance. We found that a short-scale (starting from ∼0.1 AU) Type-I migration with an inner disk edge is most consistent with the formation of TOI-1136. A low disk surface density (Σ1AU ≲ 10^3g cm^−2; lower than the minimum mass solar nebula) and the resultant slower migration rate likely facilitated the formation of the 7:5 second-order MMR.

TOI-1136 is a pristine example of the orbital architecture produced by disk migration before any subsequent dynamical evolution has had time to alter the orbital architecture. While the formation of the terrestrial planets in our Solar System was probably violent involving giant impact collisions ( Late Heavy Bombardment) that resulted in a non-resonant configuration. Our recent discovery of TOI-1136 demonstrates the possibility of a dynamical quiescent evolution that preserves an initial resonant configuration and is in stark constrast with our Solar System.