Spot-crossing events

The so-called "spot-crossing events" happen when a transiting planet occults a star spot which is cooler hence darker than the averaged photosphere (see below). This results in a temporary increase of the observed flux. If unaccounted for, the spot-crossing events could be a nuisance, biasing the inferred transit parameters and corresponding planetary properties. However, it was later realized that spot-crossing events can be used to infer stellar obliquity, the angle between the star's rotation axis and the planet's orbital planet. Stellar obliquity in turn can tell us about the dynamical history of the planetary system.

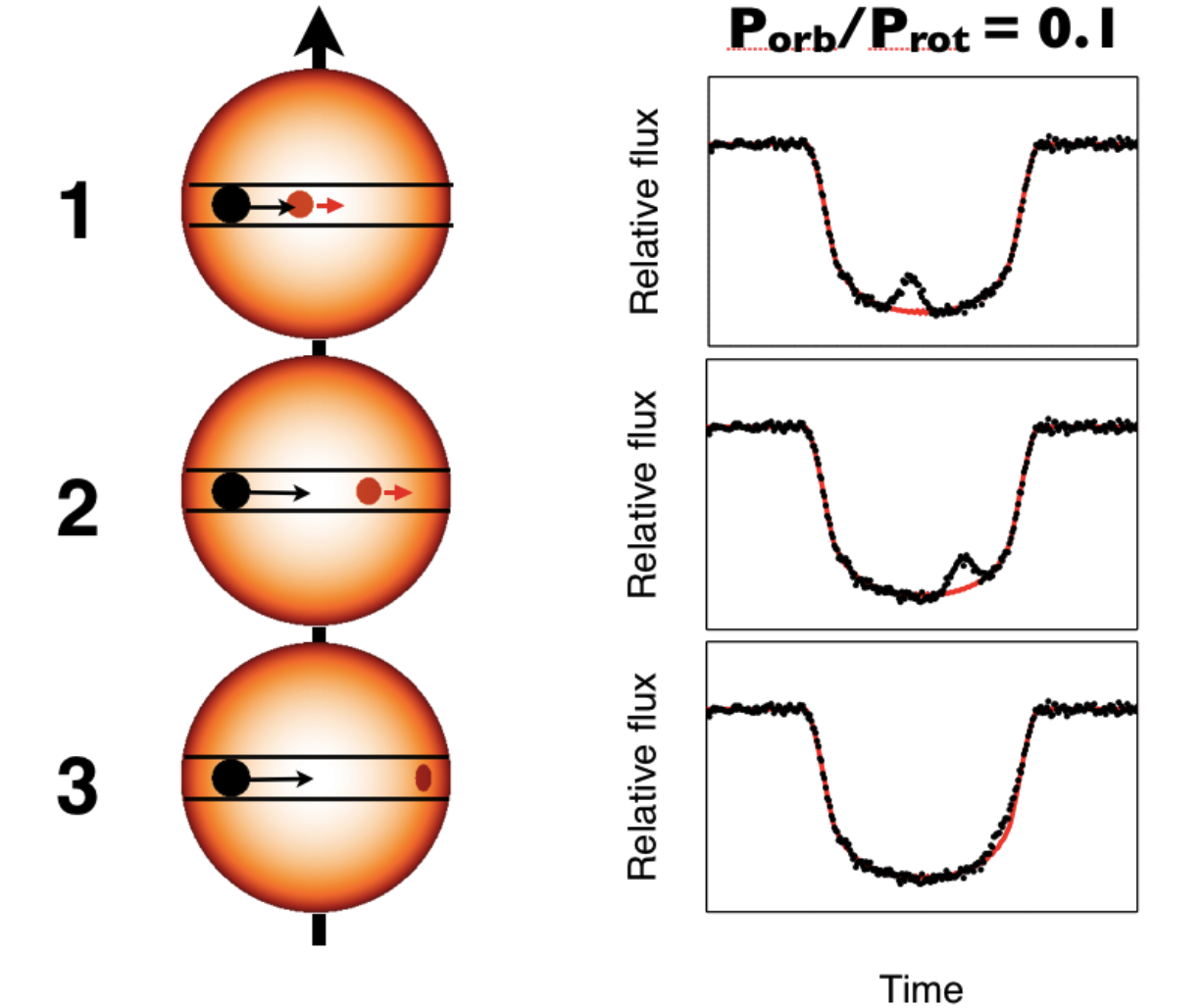

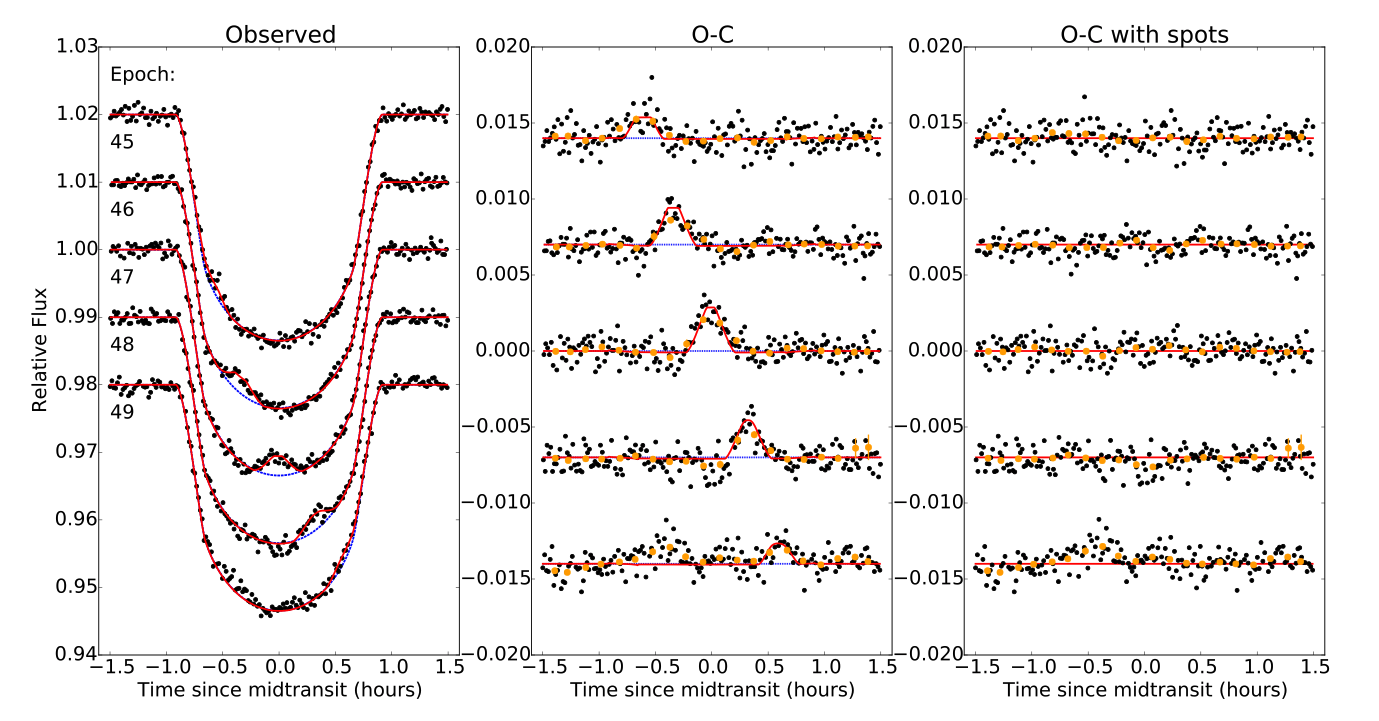

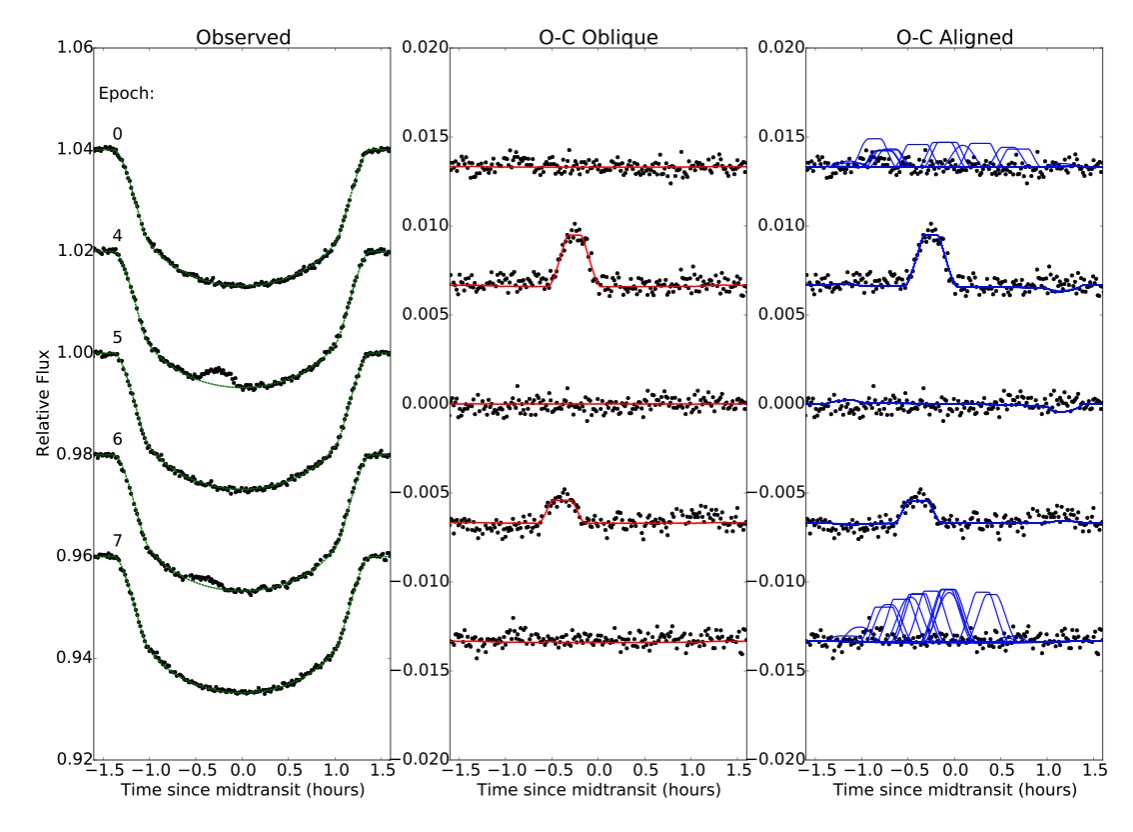

The basic idea of inferring stellar obliquity is simple. In a well-aligned (low-obliquity) geometry, the transit chord of a planet largely overlaps with the trajectory of a crossed star spot. This alignment allows the planet to occult the same spot over multiple transits. The recurrence of spot-crossing events in the observed light curve hence reveals a low stellar obliquity. A prime example is Qatar-2b, a 1.34-day hot Jupiter around a K dwarf. Recent K2 observation in the short-cadence mode unveiled dozens of spot-crossing anomalies. By modeling the recurring spot-crossing events in five consecutive transits, we ( Dai et al 2017) showed that the system has a stellar obliquity less than 10 deg. Esposito et al (2017) later confirmed the low obliquity (λ = 0 ± 10 deg) with Rossiter-McLaughlin measurement from HARPS-N.

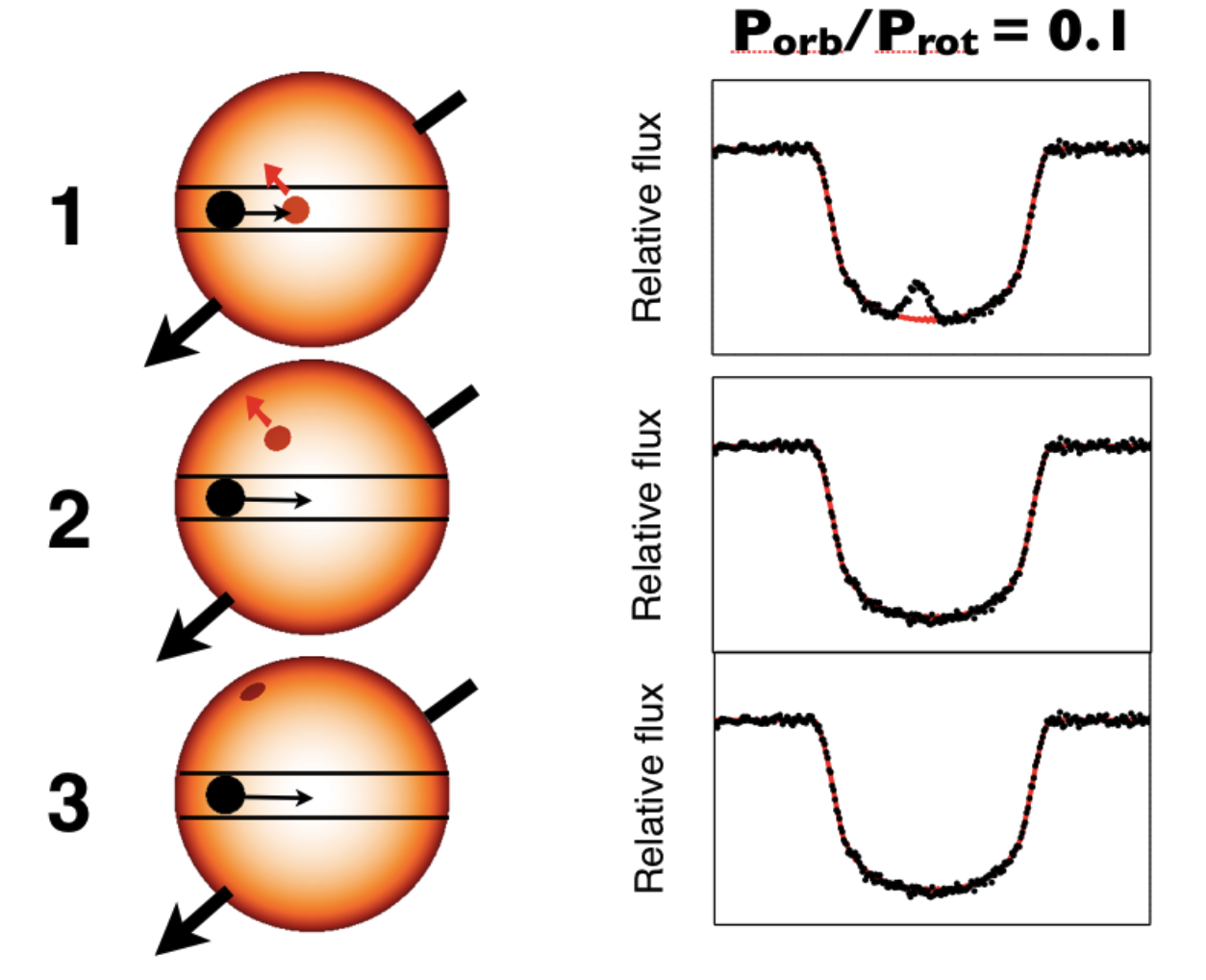

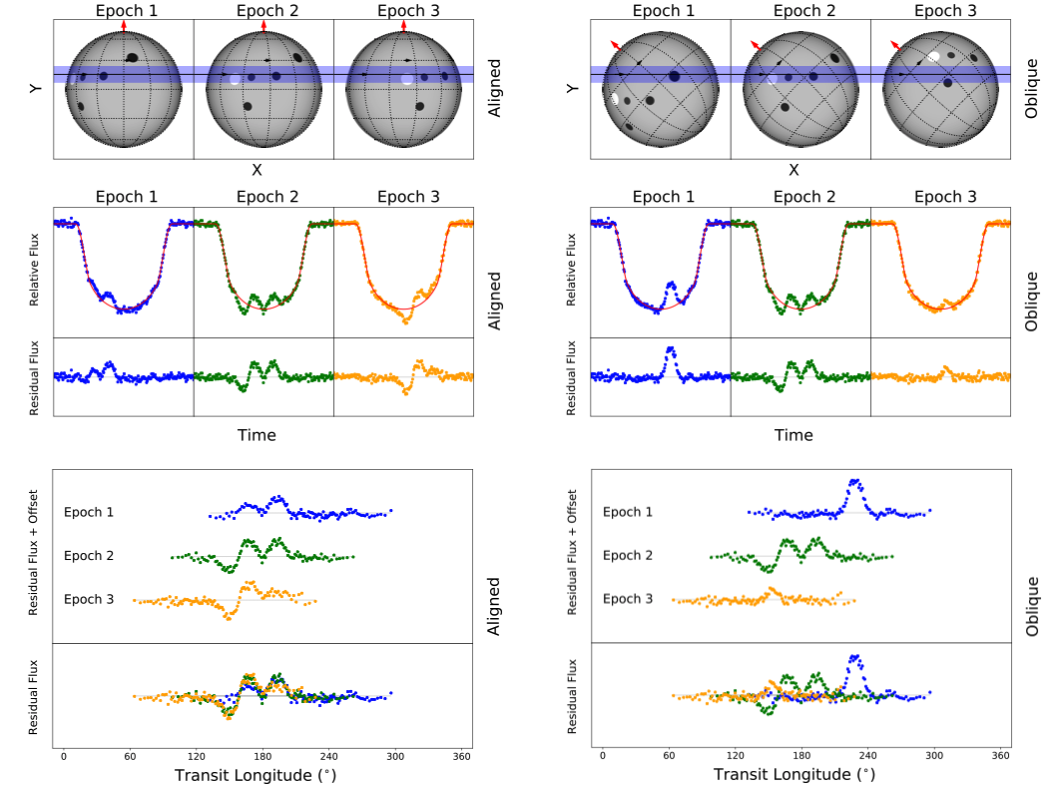

Conversely, if spot-crossing events did not recur as expected. one can put a lower limit on the stellar obliquity. Provided that spots last long enough, the absence of additional spot-crossing events implies a minimum obliquity such that the transit chord misses the star spot. This seems to be the case for WASP-107b, a super-Neptune (M = 0.12 Jupiter mass, a/Rs =18.2) around a K dwarf. The short-cadence K2 light curve of WASP-107 showed three isolated clear spot-crossing events. These spot-crossing events did not recur in neighboring transits as would be expected for a low-obliquity geometry. With a Monte-Carlo simulation, we ( Dai et al 2017) demonstrated that WASP-107 has a high obliquity in the range of 40-140˚. The high obliquity has been confirmed by Rossiter-McLaughlin measurement (Triaud et al, in prep). WASP-107 may be a member of the recently discovered "hoptunes" ( Dong et al 2018) i.e. singly-transiting, Neptune-sized or super-Neptune planets. Indeed many of these hoptunes (WASP-107b, HAT-P-11b, Kepler-63b) appear to be misaligned with their host stars, a phenomenon often seen for their bigger brothers: hot Jupiters. The striking similarities between the two groups may hint at a common dynamical origin.

Transit Chord Correlation

In Dai et al 2018, we moved from parameteric modeling of spot-crossing events presented above to a more general and more efficient statistical method which we call Transit Chord Correlation.

We applied this method to a few dozens of CoRoT, Kepler and K2 transiting planets with the highest signal-to-noise ratio light curves. We found 10 planetary systems which most likely have a well-aligned orbit as indicated by the strong correlation. Owing to their deep and frequent transits, all of the detected low-obliquity planetary systems are hot Jupiters. Notably, Kepler-45 is only the second M dwarf with an obliquity measurement. The traditional Rossiter McLaughlin method has not had much success with M dwarf because of their higher stellar variability, slower stellar rotation, and fainter optical magnitudes. We also applied the method to about 30 eclipsing binaries, and we found 8 systems that likely have well-aligned orbits.

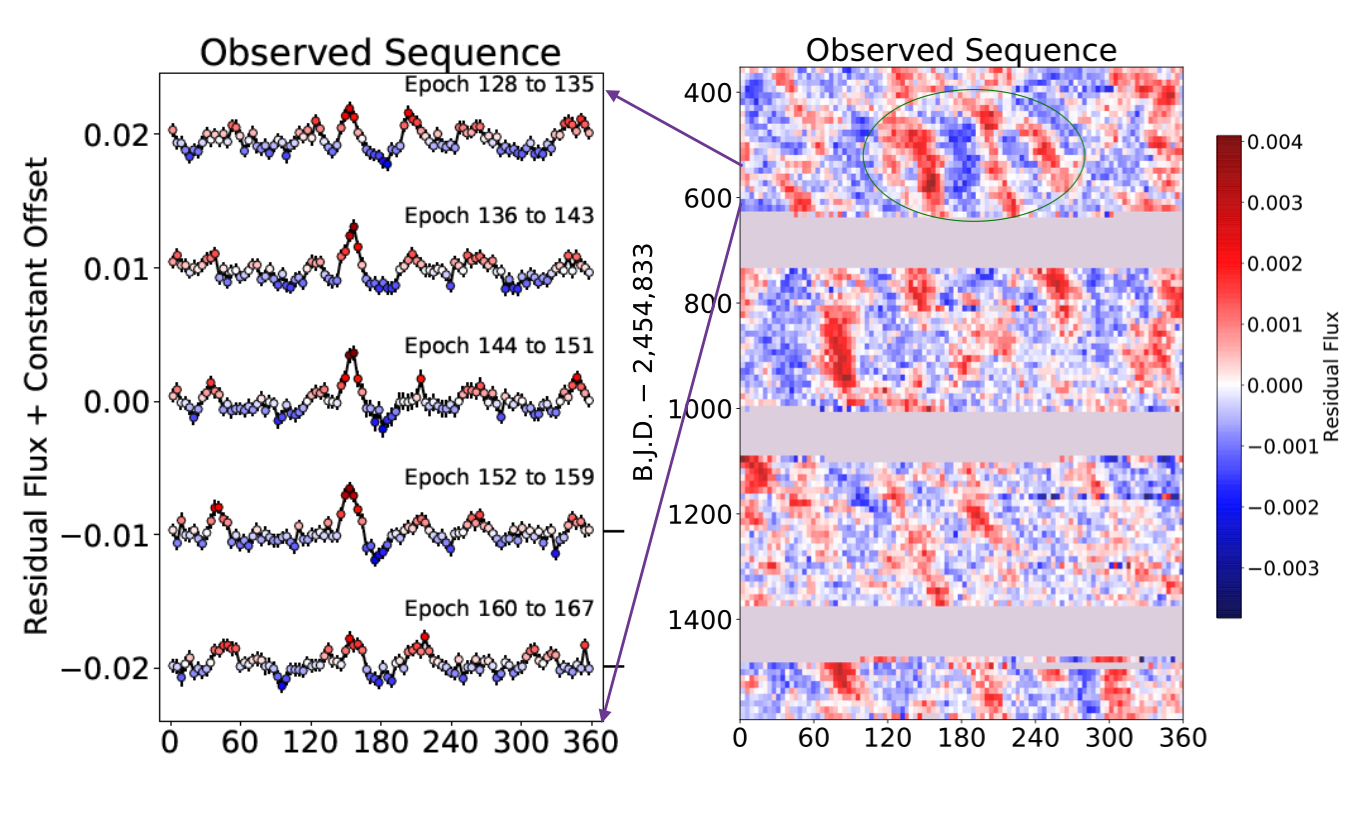

Once a low obliquity is confirmed for a system, i.e. the planet probes a particular stellar latitude repeatedly. One can then reverse the argument. By analyzing their photometric signatures of the active regions, we can study the typical lifetime, spatial distribution, and migration of active regions on the host stars. The figure below illustrates the surface magnetic activity of Kepler-17 as revealed by its planet.

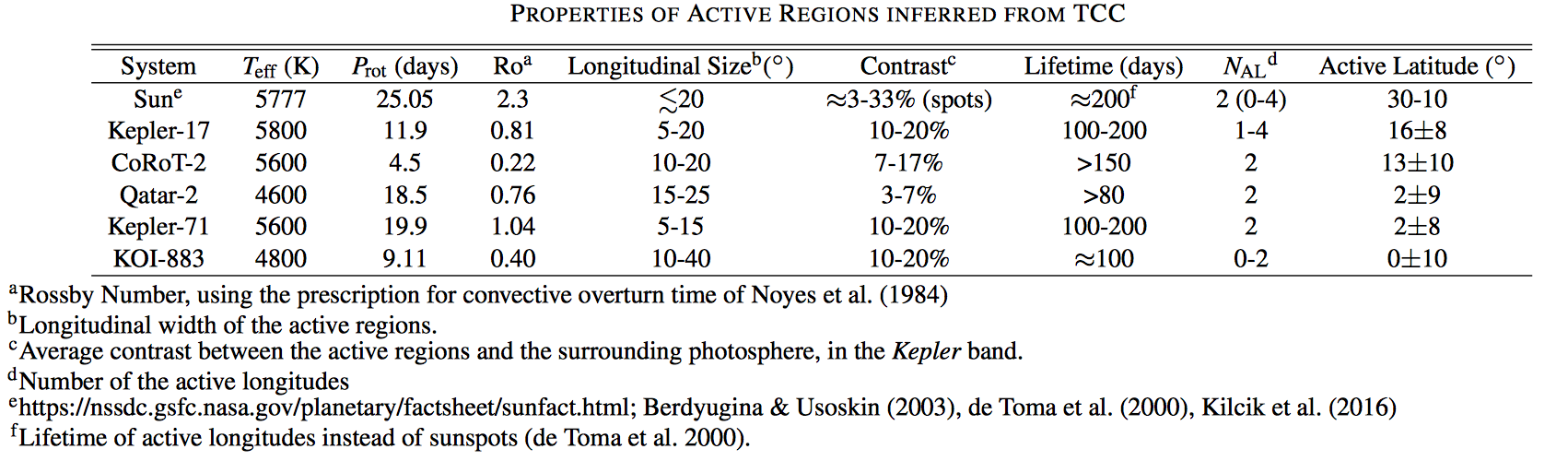

We summarize and compare the properties of the active regions of a few planet hosts with the highest SNR. The Sun is also shown for comparison. Listed in this table are several key properties of stellar activity such as rotation period, size and lifetime of active regions, the active latitude. In many respects, the active regions of these planet hosts are quite similar to our Sun. Measurements of this nature will serve as useful constraints for stellar dynamo theories.