What is a Super-puff?

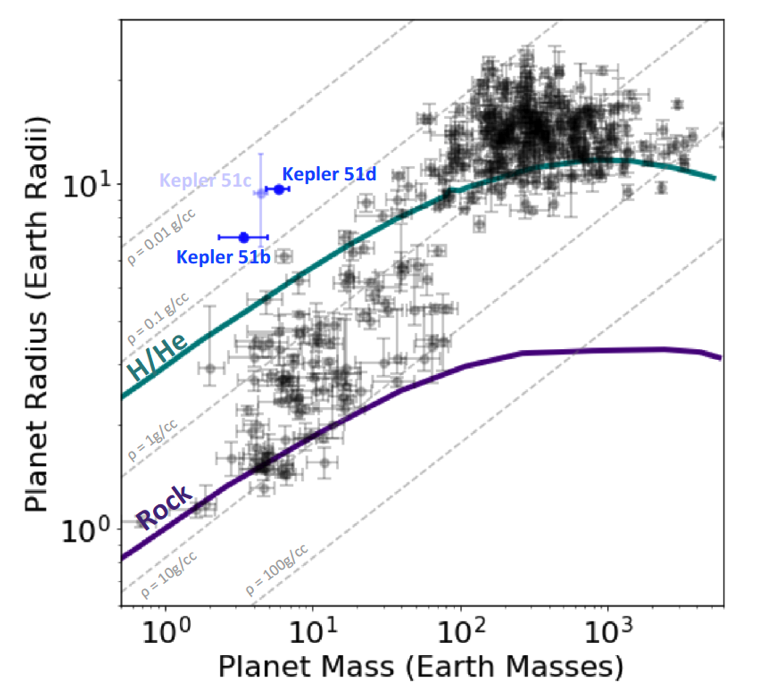

A super-puff is a planet with a super-Earth mass (less than 5 M⊕) but a gas giant radius (larger than 5 R⊕). If you plot them on a mass-radius diagram with other known exoplanets, they are clearly outliers. Their mean density can be as low as 0.1 or 0.01 gcm^-3 (similar to the density of cotton candy). This is one or even two orders of magnitude lower than most exoplanets. A prime example is the Kepler-51 systems ( Masuda 2014). The host star is a young (~300Myr) sun-like star. It has 3 transiting planets near 1:2:3 mean-motion resonance.

Why are Super-puffs so puzzling to theorists?

Firstly, the extended atmosphere on super-puffs is bound to undergo excessive mass loss. The same issue was noted and discussed at length by Owen & Wu 2016 . They call this phenomenon “boil-off”. They were literally scratching their heads about the super-puffs, as their model predicts that super-puffs would lose their atmosphere in just thousands or tens of thousands of years which is much shorter than the age of the planetary systems (hundreds of Myr or older).

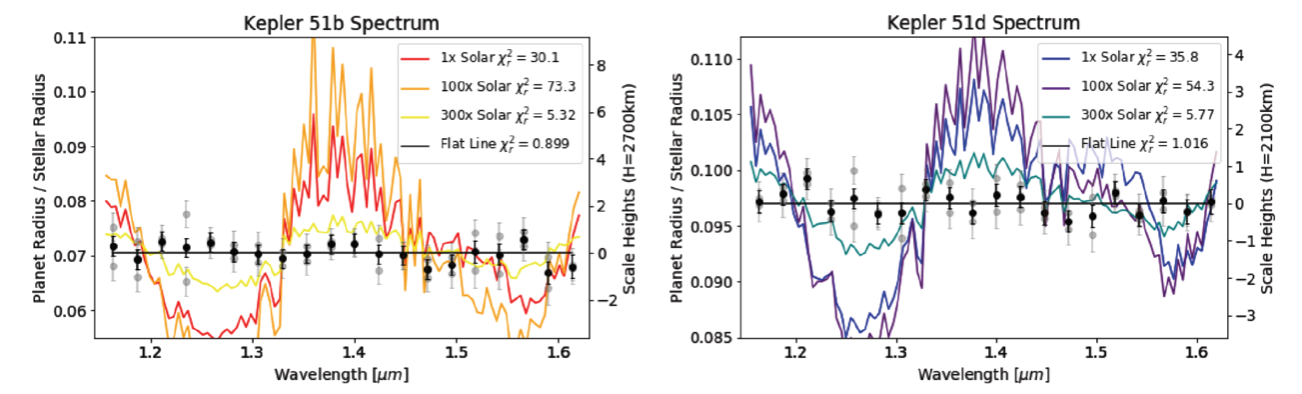

Perhaps even more puzzling is that the extended atmospheres on super-puffs also translate to very large scale heights. For Kepler-51b, the H is 3000km compared to 10km on Earth. The large scale heights would make super-puffs ideal targets for transmission spectroscopy. Yet, recent Hubble observation by Libby-Roberts et al. 2020 showed that both Kepler-51 b and d have completely flat transmission spectra in the near infrared.

If we invoke clouds to explain the flat transmission spectra on Kepler-51 b and d. One would require cloud formation at a pressure level of 0.1 mbar level. Assuming equilibrium chemistry, clouds form where the Pressure-Temperature diagram of Kepler-51 b and d intersects with the condensation curves of nearly all relatively abundant cloud-forming species. On Kepler-51 b and d this happens at about 1bar level much deeper than the cloud deck required to mute absorption features.

A Simple Solution: Dusty Outflows

This remained a puzzle for years. The solution we came up with is quite simple (Wang & Dai 2019). We considered a non-static atmosphere characterized a moderate outflow of 0.1 M⊕/Gyr. Such an outflow is slow enough to be consistent with the system’s age of 300 Myr. In other words, it preserves a H/He based atmosphere. On the other hand, it is fast enough that it carries with it small dust particles to high altitudes. The increased opacity at high altitude inflates the observed transit radius of the planet while it also mutes any absorption features. This would simultaneously explain the puffiness of the planet as well as the flat transmission spectra.

This Dusty Outflow scenario may not be as crazy as it initially sounds because mass loss from sub-Neptune planets seems to be a common if not ubiquitous phenomenon. This is manifested by the pronounced bimodal radius distribution of sub-Neptunes. Within the photoevaporation picture, a sun-like star is active in X-ray and extreme ultraviolet during the first few hundred Myr of its lifetime. Kepler-51 b and d, being around a 300-Myr-old host star, is expected to be actively losing their atmosphere through the photoevaporation.

Our work was recognized as the first viable explanation of the super-puffs, and it was featured the AAS Nova website