Friends of Palomar Observatory Website

Upcoming Events

Greenway Talks schedule

The Newsletter of the Friends of Palomar Observatory, Vol. 16 No. 1 – June 2021

Hale Primary Mirror Travel Log

By Andy Boden

Mirror transit slideshow. Click to start. Use < or > to reverse or advance one slide, or the progress dots to jump slides (this pauses the slideshow). Click any image to enlarge and on some captions for further context. The slideshow will pause for videos.

Readers fluent in the Hale Telescope creation story may well recognize the name Belya: Belya Trucking and its principal Jack Belya played a key role in transporting the mirror both on its 1936 Pasadena arrival and in its painstaking 1947 transit from Pasadena to Palomar. Recently we were contacted by members of the Belya family to discuss recognition of their family’s role supporting the Hale Telescope construction. This contact provided impetus for three of us (SBF, ACM, AFB) to do a careful assessment of the media (images and video) in our holdings. From these mirror transport media we have selected and contextualized the most engaging and informative images and video. Further with those selected media and some important web software development by Annie we have put together a topical media package focusing on telling the Hale primary mirror transport story in a visual, engaging way, and includes captions and background material for further information. We released this mirror media package on the Palomar Observatory website around 10 April this year to mark the 85th anniversary of the mirror blank arrival to Caltech. Here is an excerpt from the package context narrative:

This media package, along with more information, can be found on our website: https://sites.astro.caltech.edu/palomar/media/slideshows/mirrortravellog.html

The observatory has a great many image assets in its holdings, and as Annie and I worked on curating this particular media package, we started getting grander plans of how this method might allow us to make other thematic media collections available to the public: on the web or in the informational kiosks in the Greenway and Cahill centers. We are grateful to the Belya family for helping to motivate this development. And we are excited to see where this method will take us, and how we might be able to share more of the observatory’s history, legacy, and community with our friends near and far.

It Was a Dark and Stormy Night

By Steve Flanders

In an unsigned, front page article on September 24, 1934, the Los Angeles Times announced that a deal had been signed “that will place the world’s largest telescope atop historic Palomar Mountain.” The deal was closed at a meeting of “representatives of the California Institute of Technology, the owners of the mountain top table-land, and the San Diego County Board of Supervisors.” San Diego County was represented because the County had agreed to build a road to the Observatory. One of the landowners at the meeting was rancher William Beach. He sold 120 acres to Caltech that night while he also provided the meeting’s venue, a log cabin of his own construction that he shared with his wife, Marion.

The author of the Times’ article describes the circumstances of that meeting at length. Signatures were gathered and papers were signed, the text continues, “by five men [sitting] around an old-fashioned wooden table” who worked “by the flickering light of a kerosene lamp and with a mountain storm raging outside the weathered cabin more than a mile above sea level.” The meeting continued long into the night so that eventually “candles were substituted … when the kerosene lamp ran dry.” And, since “the agreements were signed shortly after 3 a.m., [the] negotiators had to await the drying out of the roads before returning to the city.” [1]

At this meeting in the backwoods, through its representatives Caltech made a commitment to build George Hale’s last great telescope on Palomar Mountain. For the members of the Observatory Committee, it was a significant moment that marked the beginning of the project’s large-scale construction phase—the dome and support infrastructure on the mountain and the fabrication of the telescope’s mounting in South Philadelphia.

As the Los Angeles Times would have it, this was a moment of transition and cultural change, inherently of significance to everyone living in the society. Seemingly, the howling wilderness of Palomar Mountain was now being forced to give way to science and civilization. But larger issues were involved because the author of the article goes on to say that, as a result of this deal, “Southern California was assured a scientific institution which will comprise one of the wonders of the world.” [1] Clearly, some complex cultural dynamics were in play. Perhaps, the “wild west” itself was being civilized and modernized by Caltech’s actions.

If this first land deal was significant to the stakeholders of 1934, the act retains its significance in the history of Palomar Observatory. It is the point of origin for the great story we tell the public about the success of the Observatory, a story that talks about the persistence of its leadership, the skill and creativity and innovative energy of its engineers, and about the age of scientific discovery that for seven decades has been sustained by the combined efforts of its scientists and staff members.

Top: William Beach at the eyepiece of the telescope in 1933. (San Diego History Center). Bottom: For the seeing tests, Beach used a 4-inch refracting telescope designed by Russell Porter similar to the one in this picture. (Palomar/Caltech)

William Beach and the events that took place in his tiny cabin during an early season Pacific storm in 1934 are essential elements in this great story.

No trace of the cabin itself remains, and the only visible remnant is what appears to be the foundation of a stone and concrete fireplace 300 yards southeast of our Outreach Center and almost a half mile northwest of the dome of the 200-inch telescope.

William Beach remains one of the interesting characters in this story. He sold a tract of land as a building site to Caltech, 120 acres that represented a large portion of the ranch he and his stepbrother, Kenneth, operated on the mountain. And to close the deal, he opened the home he had built and was then sharing with his wife, Marion, to the landowners and representatives of Caltech as well as to the people from San Diego County and the Cleveland National Forest.

Moreover, in 1928 William Beach became a part-time Caltech employee and, for the next six years, he conducted nightly tests of atmospheric seeing and recorded measurements of the mountain’s weather conditions. By amassing these records, Beach provided the evidence that the Observatory Council would need to move forward in its site selection process.

But there is a further and perhaps more interesting aspect to the story of William and Marion Beach, their cabin and the founding of the Observatory. According to Ronald Florence, it was common knowledge that “Hale had favored Palomar from the beginning.” [2] As a consequence, many people from Pasadena began making trips to the mountain where they could judge conditions for themselves and where they could lodge at the Beach’s cabin and enjoy the Beach’s hospitality.

In fact, William and Marion had, for some time, been operating something akin to a mountain hostelry. Commonly, they catered to hunting parties, but the astronomers were no less welcome. We know of their visits because we have copies of the guest book William and Marion maintained. What follows is a compilation of the signatures of nine cabin guests who signed the book and who all made significant contributions to the founding of the Observatory.

In the years after 1928, many interesting and important people made their way from Pasadena to the little cabin on the mountain. They came from Caltech and from the Carnegie Institution’s Mt. Wilson Observatory and frequently they rubbed shoulders with guests who endured the rigors of the mountain not for science but simply for the personal pleasures of a day’s outing. And, from their comments, it is apparent that at least a few of the astronomers and engineers enjoyed the time they spent as the Beach’s guests.

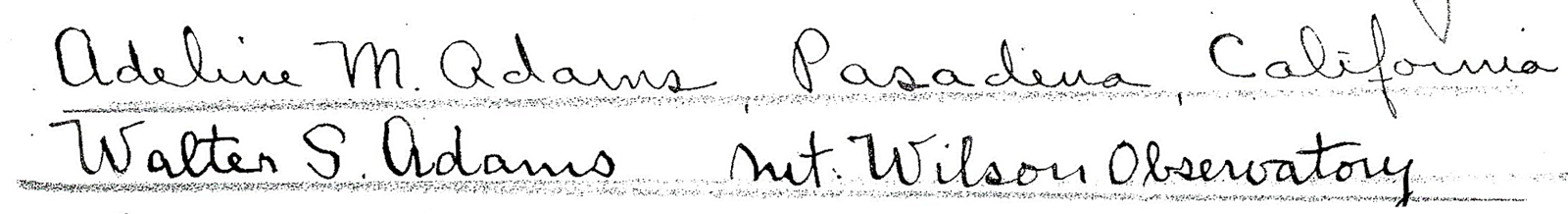

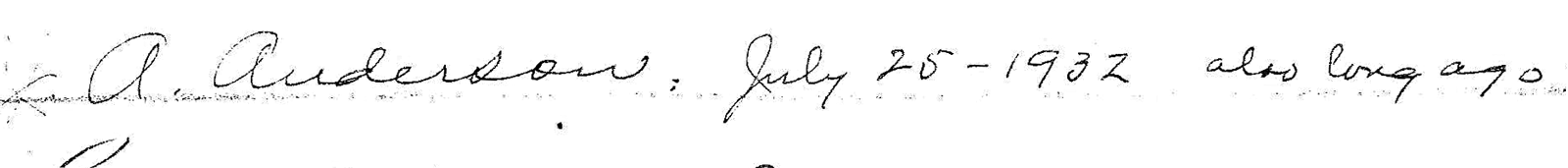

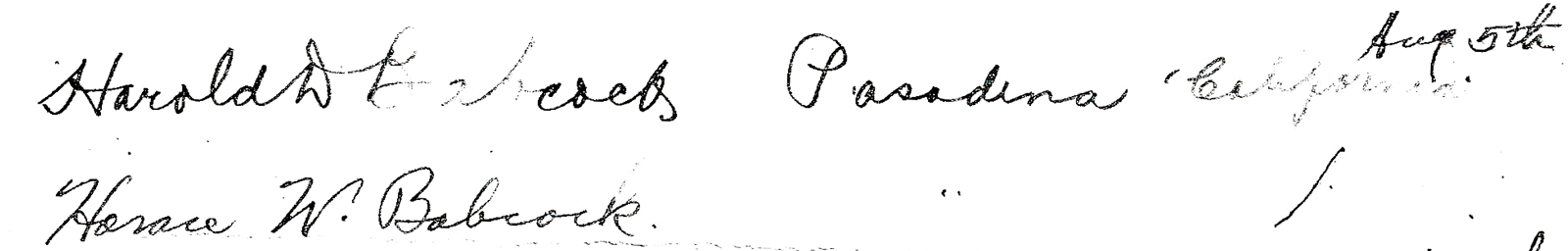

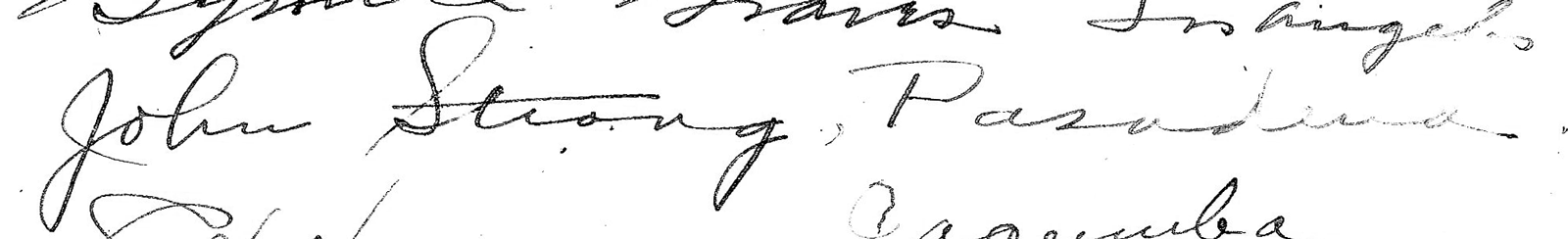

Select Beach guest book entries:

Walter Adams, Mt. Wilson Observatory Director, and his wife Adeline.

John Anderson, Executive officer of the Observatory Council.

Harold Babcock, Mt. Wilson Observatory staff astronomer, and his son Horace, Palomar Observatory staff astronomer, later Director of the Hale Observatories.

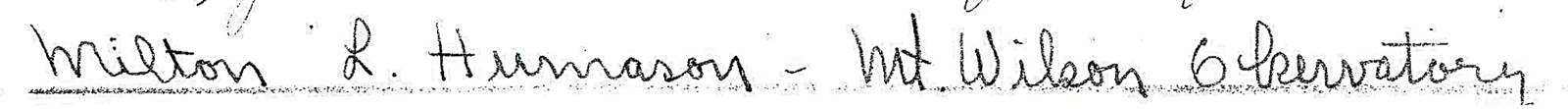

Milton Humason, Mt. Wilson Observatory staff astronomer.

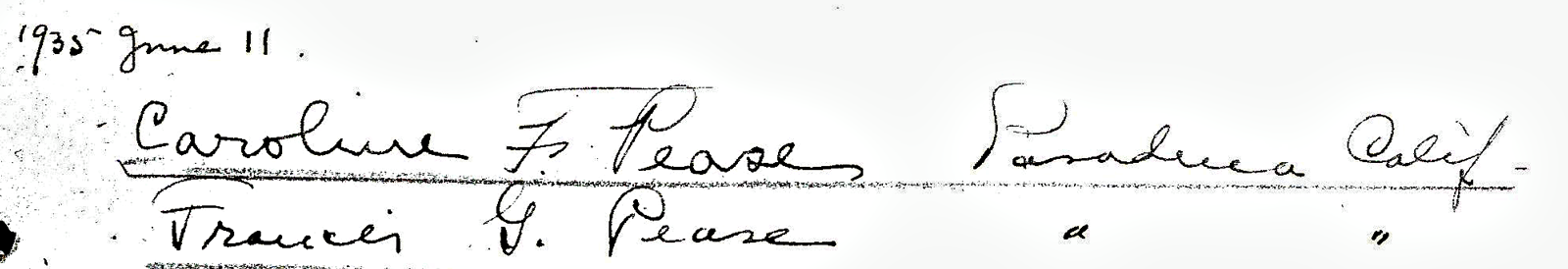

Francis Pease, Mt. Wilson Observatory staff astronomer, and his wife Caroline.

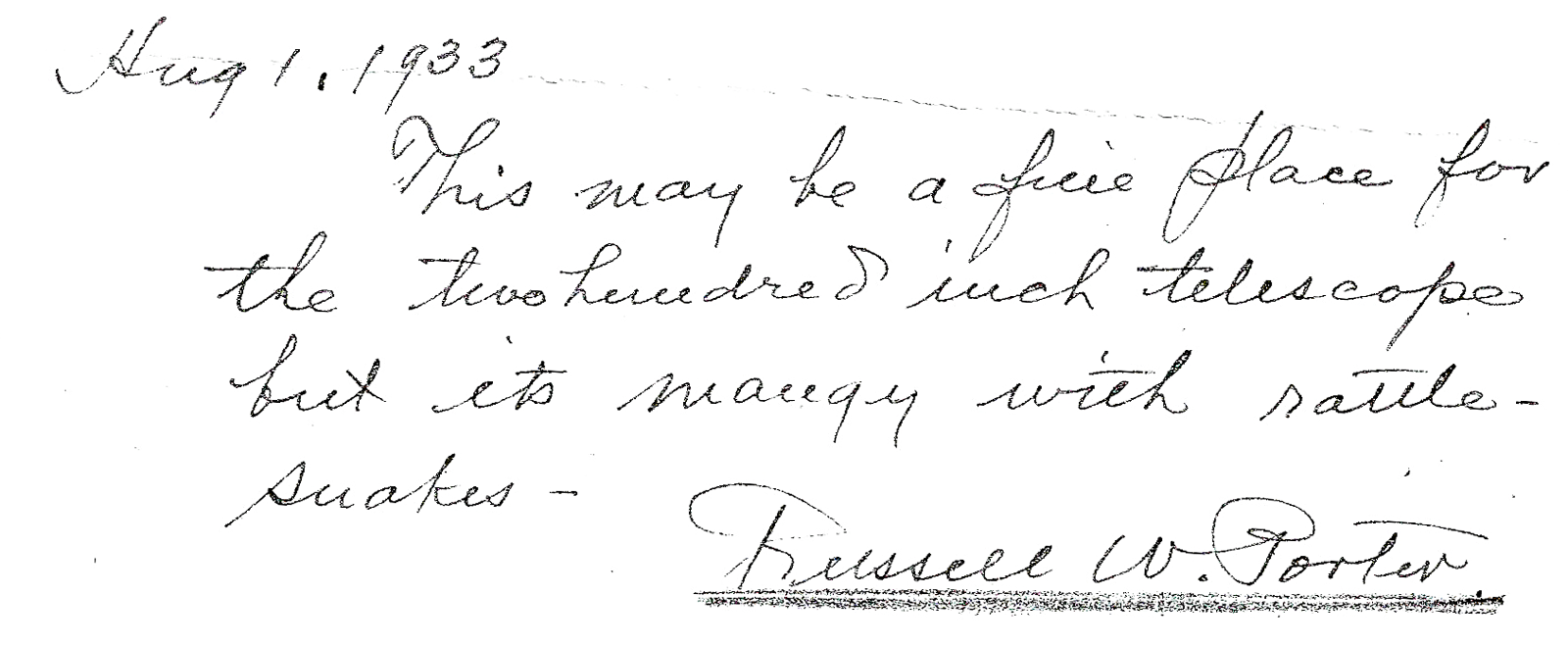

Russell Porter, optical, graphic and instrument designer, Palomar Observatory.

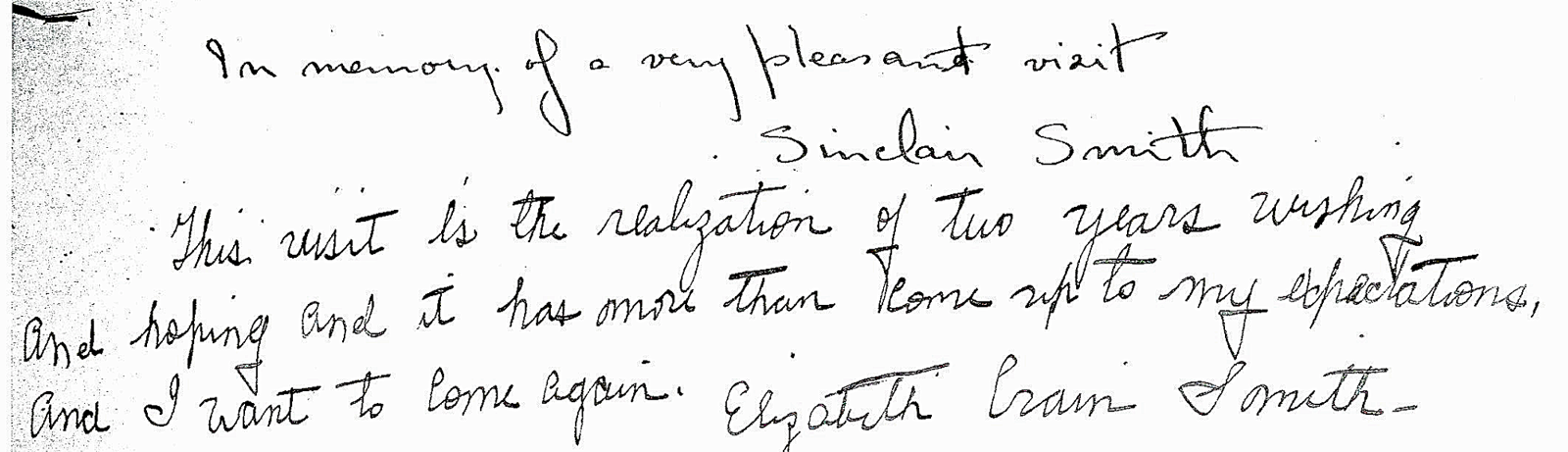

Sinclair Smith, Mt. Wilson Observatory staff astronomer, with his wife Elizabeth.

John Strong, Caltech research fellow.

But these pleasant times could not last. It is not clear whether Beach’s initial sale of 120 acres to Caltech on September 21 and 22, 1934 included the land on which his cabin stood. The issue is uncertain because William and his wife continued to live on the property for a period following the sale.

Whatever the case, we know that their time as innkeepers to the stars ended within a few short years. In 1940, the U.S. Congress passed legislation that enabled Caltech to acquire land from the Cleveland National Forest. By the end of that year, Caltech occupied 1,400 acres on the mountain, a tract that undoubtedly included the site of the cabin Bill Beach had built for his new bride more than a decade earlier.

In fact, the Beach family—Bill and Marion and Bill’s stepbrother, Kenneth—seem to have been long gone from the mountain by 1940. Since the early 1920s, Beach had been listed on a register of residents of the Palomar district compiled annually by the County of San Diego. He and his wife appear on this register for 1935 but are absent thereafter. The last entry in their guest book is dated September 21, 1936. And, with their departure, the cabin likely was dismantled by neighbors anxious to exploit a ready supply of low-cost building materials.

Still, for six years beginning in 1928, as William tabulated sky conditions at the site, he and his wife also contributed to the founding of Palomar Observatory by opening their home and their hospitality to a succession of planners and builders from Pasadena. We know of a few of their visitors because the Beaches maintained a guest register. But others may have stayed without making an entry in the book and without leaving a record of their presence.

Most notably, we know that George Ellery Hale travelled to Palomar on several occasions. He made an important inspection tour in March 1934 with Adams and Anderson. It was Hale’s last visit to the mountain and the last visit made by any of them prior to the Observatory Committee’s approval of the Palomar site. Unfortunately, none of the three men entered their names in the Beach’s guest book in March 1934.

For all of this, I have offered no evidence in support of my claim that this is the site of William Beach’s cabin. The reason for this omission is that the several lines of evidence are all circumstantial and following any one of them takes us deep into the weeds of this story. The details can become overwhelming and in any case explanations of this sort are beyond the scope of this short article. However, I will try explaining some of the evidence in a talk I am giving on July 3 for the Greenway Talks Online.

References

- Telescope Deal Made, LA Times (September 24, 1934) vol. 53, p. 1.

- Ronald Florence, The Perfect Machine: Building the Palomar Telescope (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1994), p. 209.

Observatory Update

By Andy Boden

Palomar is slowly emerging from the defensive posture the observatory assumed at pandemic onset. Here are some quick updates on operations and development items moving toward more normal operations:

- For most of the pandemic we operated the Hale Telescope on a limited duty cycle. I am happy to report that starting in May 2021 we resumed the normal full duty cycle (i.e. open every clear night) with the Hale. In addition we had curtailed some instrument operations, but we have now scheduled a return to service for all our facility Hale instruments. [The last instrument to return to service is the Palomar Cosmic Web Imager].

- In order to maintain flexibility with evolving pandemic conditions the Hale science schedule had been set only a month at a time (see previous newsletter discussion). However I am very excited to report that we have just published our first full-semester Hale Telescope schedule for the coming semester (2021B: August 2021 – January 2022 inclusive). Our science users are happy to return to a more normal operating cadence that allows them to schedule their activities farther in advance, and I am particularly happy that I don’t have to create a new schedule every month!

- Starting in June we have resumed limited “Monastery” (astronomer’s quarters) occupancy and operations. We are thankful to our longtime Monastery service partners Yoga in Service Corporation for working with us throughout the pandemic conditions, and we are excited to be bringing this long Palomar tradition back into operation.

- We are starting to bring Hale observers back to the telescope on a limited basis. Only a few astronomers each month will be invited to come to Palomar for the first few months, but we are looking forward to gradually opening to all Palomar observers sometime in the fall.

Many readers will be wondering when we will reopen the Observatory to our many friends and the visiting public. Those discussions are actively ongoing here at Caltech, and we are starting the planning process for a public reopening later in 2021. When we do have a definite public reopening plan we will announce it on the observatory website.

Questions? We've answered many common visiting, media, and academic questions in our public FAQ page.

Please share your feedback on this page at the

COO Feedback portal.

Big Eye 16-1

Last updated: 11 June 2021 AFB/SBF/ACM