Photoevaporation

Since photoevaporation is the likely culprit for producing the bimodal radius distribution of small planets ( see here), we decide to investigate the process of photoevaporation further.

Specifically, we wanted to address the following questions:

1. How important is the detailed microphysics such as the photo-thermo-chemistry of dusts and molecules?

2. Can the ram pressure of a strong stellar wind quench photoevaporation as Murray-Clay et al 2009 suggested?

3. Can high energy radiation penetrate deep enough into the atmosphere? If so, what kind of high energy radiation is more important for driving the outflow: EUV or X-ray?

4. How does the outflow look like? Is it isotropic? How do we look for it observationally?

Lile Wang and I ( Wang and Dai, 2017 ) carried out axisymmetric hydrodynamic simulations. We also incorporated a self-consistent chemical network, as chemical species and their ionization state determines the heating and cooling mechanisms. We included FUV, EUV and X-ray (7eV to 1keV) photons. The amount and the time evolution of the high energy radiation was adopted from Ribas et al 2005. Our planets have an Earth-like core with a convective H/He atmosphere and an isothermal layer on top. The hydrodynamics is computed with Athena++.

The temperature, density and velocity profile of a photoevaporating planet. Stellar irradiation is coming from the left of the page.

We found that EUV is the most important driver for photoevaporation: the kinetic energy imparted by the high energy photon is simply roughly hf - ionization energy. Hence in order to escape the gravitational potential of the planet, the energy of the photon has to reach the requisite energy level. FUV generally does not have enough energy.

X-ray seems less important: although X-rays have higher energies, X-rays also have smaller interaction cross sections than EUV photons. Hence X-rays tend to penetrate deeper into the atmosphere, where density is higher. With a higher density, collisional excitation and dusts present in the deeper atmosphere quickly rework the energy to infrared radiation that escapes easily. Hence with X-ray alone, the atmosphere cannot reach a temperature high enough for hydrodynamic outflow.

We also found that stellar wind is not able to quench photoevaporation. In a 1D simulation, the stellar wind is treated as a pressure term, and serves as a confining force. Naturally, if this term is strong enough, hydrodynamic outflow can be quenched. However, in reality stellar wind only impinges the planet on the day-side. In our 3D simulation, we can see that stellar wind directs the outflow to the night side but does not quench it.

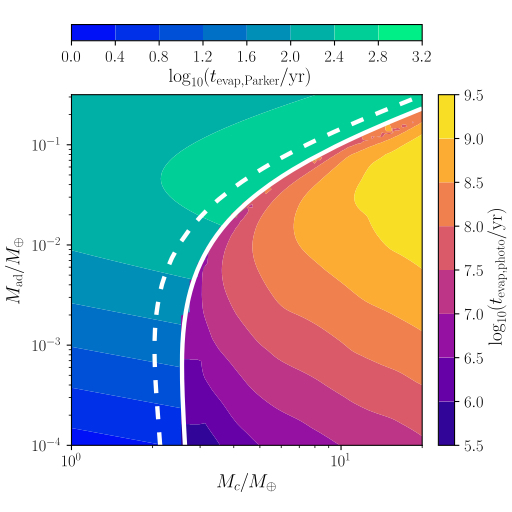

By carrying out a suite of simulations with different initial conditions, we mapped out the timescale of photoevaporation as a function of planet core mass, envelope mass fraction and the amount of stellar high energy radiation. We identified three regimes of atmospheric loss:

1. For planets less than ~3 M⊕, thermal Parker wind alone prevents them from having thick (larger than 0.01% by mass) H/He atmospheres.

2. On a 100 Myr timescale where the star still emits a substantial amount of high energy radiation, planets less than ~6 M⊕ will lose a significant fraction of their atmosphere due to photoevaporation.

3. Planets with a core mass larger than ~10 M⊕ are resistant to photoevaporation and Parker wind thanks to their strong gravity.

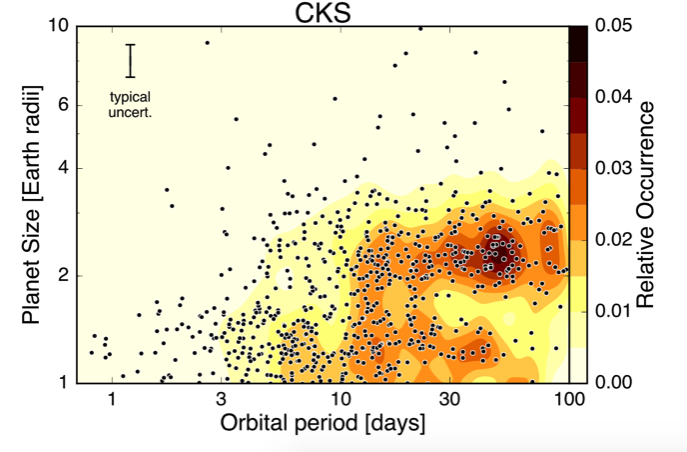

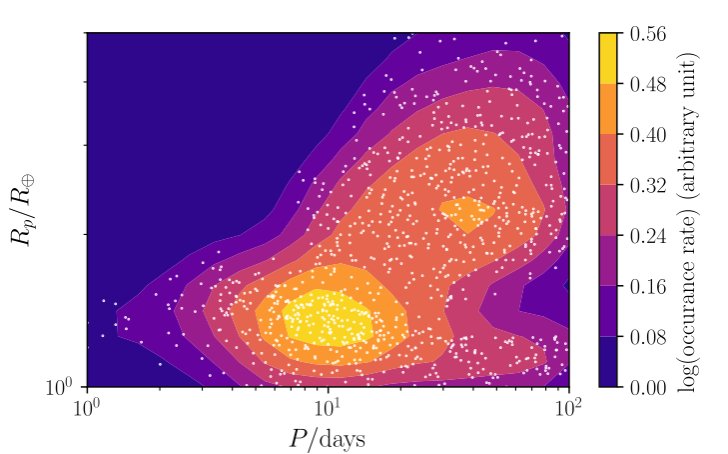

Applying the results to the planets discovered by Kepler, we were able to reproduce the observed bimodal radius distribution as well as the large composition contrast of the Kepler-36 system (see below).