What are Ultra-Short-Period Planets?

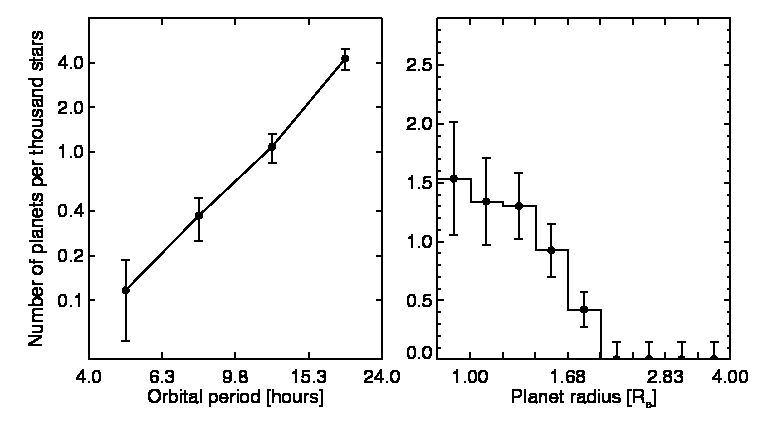

At the hottest extreme of planet formation are the so-called ultra-short-period planets (USP) loosely defined as terrestrial planets with orbital periods shorter than 1 day. They occur around 0.5% Sun-like stars, and their radii almost never exceed 2 R⊕. Often bathed in stellar irradiation thousand times stronger than that of the Earth, the surface equilibrium temperature of these planets may easily exceed 2000K, melting most of the rock-forming minerals and earning these planets the nickname “Lava worlds” or “USPs”.

The composition of USP

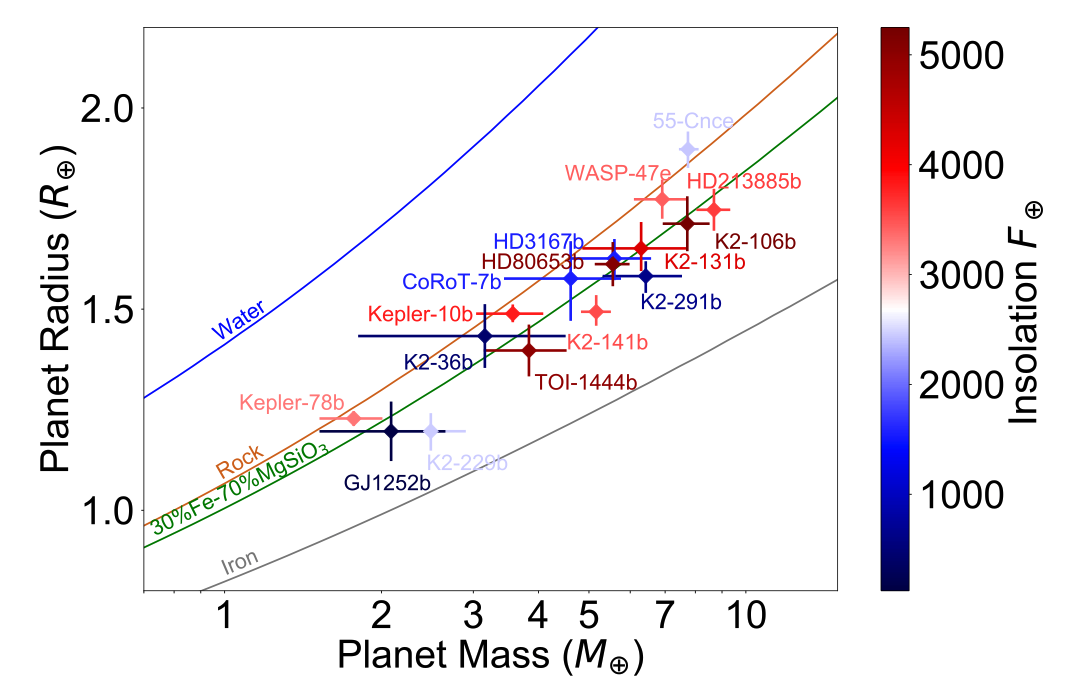

USPs may be our best chance of constraining the composition of Earth-sized planets in the near future. For a true Earth analog on 1 year orbit around a sun-like star. The induced radial velocity semi-amplitude is only ~10 cm/s. This is beyond the capability of current state-of-art spectrographs which can consistently achieve 1m/s precision. With a much closer orbit, a USP can induce radial velocity signal that is almost one order of magnitude stronger, putting it within reach of current technologies. Moreover, the photoevaporation theory predicts that many USPs should be devoid of H/He envelopes. This helps to remove some of the degeneracy in the core composition when only the mass and radius of a planet are measured.

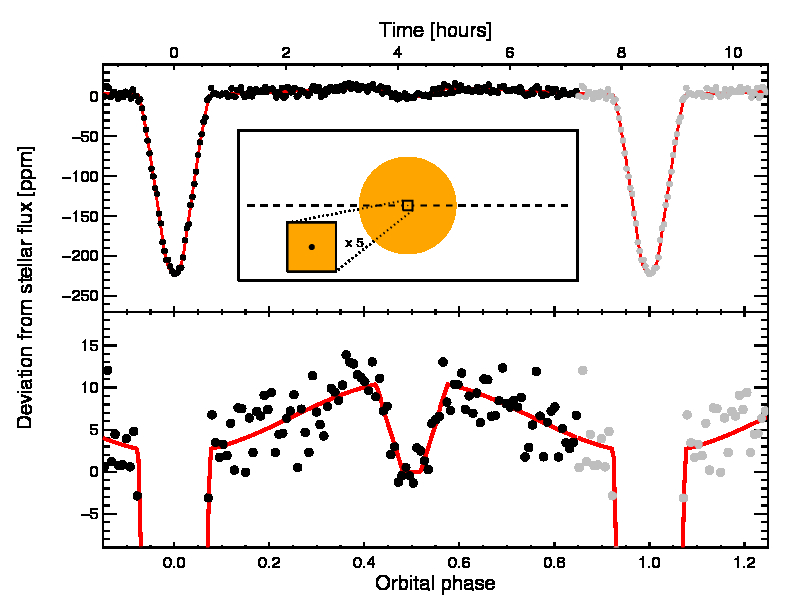

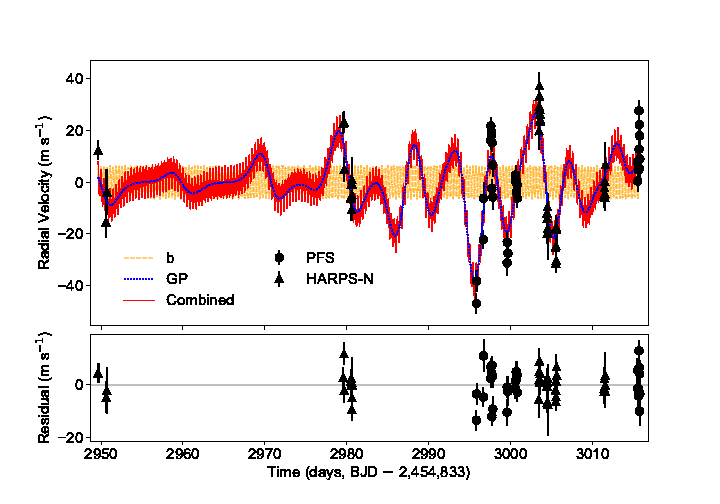

Over the past few years, we have discovered and measured the masses of 8 USP systems with the NASA K2 and TESS mission and a suite of ground-based facilities including HARPS, HARPSN, Magellan/PFS, Keck/HIRES etc. One of the great challenges in measuring the masses of these planets was to disentangle the planetary signal from the spurious radial velocity variation due to stellar activity. We used a method called Gaussian Process regression which models the correlated stellar noise with a covariance matrix. It turns out that stellar activity affects not only the measured radial velocities, but also the measured light curve in a similar fashion. One can use the light curve which is measured with better precision and higher cadence to train the Gaussian Process model before applying it to radial velocity datasets.

With this technique, we performed a homogeneous analysis of all USPs that reside in the so-called photoevaporation desert (photoevaporation desert > 650 F⊕, read more here). Planets in the photoevaporation desert should be devoid of H/He envelope that complicates the inference of planet's core composition. We used Gaia DR2 parallax to refine the stellar parameters. The resultant mean stellar density was imposed as prior in transit analysis to better constrain planet radius.

As a group, USPs are mostly consistent with being exposed rocky cores. None of the planet requires a significant amount of volatile materials which would put them between the 100% water and 100% rock lines. This lack of volatiles indicates that most USPs formed from volatile-poor materials within the disk snowline. Although individual error bar can be big, as an ensemble these extremely rocky worlds have a 32±4% iron-silicate ratio which is remarkably similar to Earth.

Orbital Configuration of USPs

At such close-in orbit (often just a few stellar radii away from their host star), the USPs presented quite a puzzle to planet formation theories. Many are within the dust sublimation radius or even the radius of the host star during the pre-main sequence. It seems very unlikely that USPs could have formed where we see them today.

Several formation scenarios have been proposed to reconcile the existence of these USPs with more conventional planet formation theories. For example, Lee and Chiang 2017 proposed that the inner edge of planet formation is set by magnetosphere truncation. Planets on shorter periods are increasingly rare because they have to be brought in by asynchronous equilibrium tides after disk dissipation.

An alternative theory proposed by Petrovich et al 2018 claims that USPs were initially the innermost planet of a multi-planet system. The innermost planets can be excited to a high eccentricity through secular interaction with outer planets. When the eccentricity is high enough (~0.8), tidal interaction with the host star takes over and start to shrink the orbits of these planets. A key prediction of this scenario is that the shortest-period planets should have high inclinations (10-50 degrees) relative to their outer planets since secular interaction often excites eccentricity and inclination together. In contrast, in Lee and Chiang’s dynamically colder scenario, the inclination of the shortest-period planets should be low.

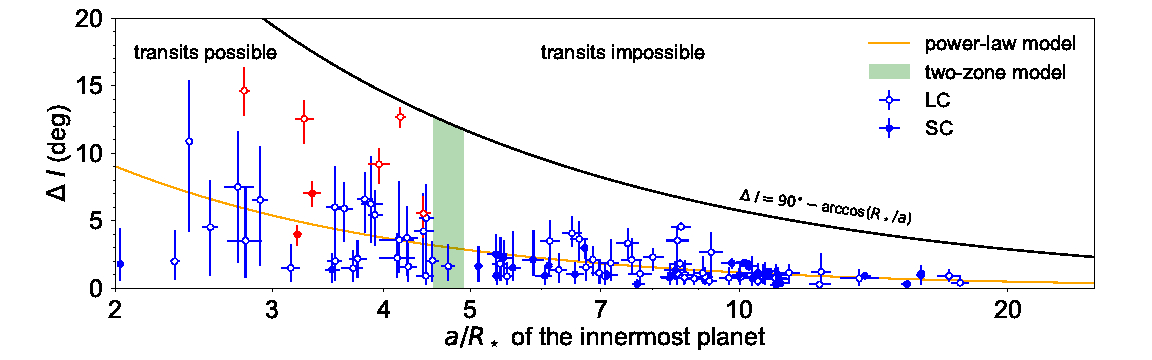

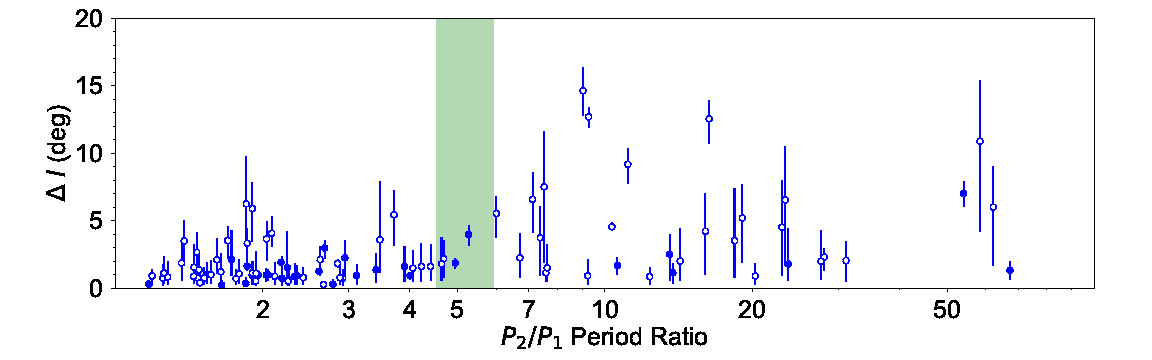

We put these ideas to test by directly measuring the mutual inclination of about 100 transiting multi-planet systems discovered by Kepler . We inferred the orbital inclinations of the planets using their transit profiles. To remove some of the degeneracies between orbital inclination and mean stellar density, we used Gaia DR2 to pin down the stellar parameters before using it as a prior in transit analysis.

Our results (Dai et al 2018) show that at larger orbital distance (a/Rs>5), the mutual inclination is generally low: less than 5 degree or so. This is consistent with previous works such as Tremaine and Dong 2012 (less than 5 deg), Fang and Margot 2012 (less than 3 deg) and Fabrycky et al 2014 (1-2 deg). However for the shortest-period planets (a/Rs less than 5), the mutual inclination fills up to the detectable range of 10-15 deg. Moreover, the higher mutual inclinations are also associated with larger period ratio between neighbouring planets. We argue that this favors a dynamically hot origin for the USPs that generated orbital shrinkage and larger mutual inclination simultaneously e.g. the "secular chaos" scenario by Petrovich et al 2018.