Upcoming Events

The Newsletter of the Friends of Palomar Observatory, Vol. 18 No. 1 – June 2024

A Shared Astronomical Heritage on Palomar Mountain

. Click ►to start. Use < or > to reverse or advance one slide, or the progress dots to jump slides (this pauses the slideshow). Click any image to enlarge and on some captions for further context.

On 10 May 2024 members of the Pauma Band of Luiseño Indians and Palomar staff and docents came together to celebrate the release of a new digital exhibit titled the First Palomar Astronomers.

Inspired by original anthropological and archaeoastronomical research by Ed Krupp (Griffith Observatory) and Palomar’s ongoing partnership with local Native American groups, the digital exhibit explores Luiseño astronomy and its role in agricultural practices and cosmogonic narratives. The exhibit was released on the Palomar website and media kiosks both at Palomar and Caltech in November 2023 during the traditional Luiseño acorn gathering season on Palomar Mountain.

In pre-industrial Southern California the Payómkawichum or Luiseño people were prevalent across large sections of present-day Orange, Riverside, and San Diego counties. Payómkawichum tribal oral history and ethnographic research places them for thousands of years in the Pauma Valley. Circa 1800 the collective designation Luiseño was created by Franciscan friars to describe the inhabitants of numerous distinct villages throughout the region including a significant seasonal presence on Palomar Mountain. Today, the Pauma Band of Luiseño Indians is a federally recognized Indian tribe—one of six bands of the Luiseño Indians in Southern California. Many of their ancient traditions and stories including their skylore and creation stories are known and told to this day.

The Pauma-Palomar relationship goes back to more than two decades when the tribe and Palomar Telescope Operator Jean Mueller first met to discuss naming three asteroids of her discovery after Luiseño traditional figures. Jean tells us her personal journey in naming these asteroids below.

Origin Story: 2009 Asteroid Naming

By Jean Mueller

My journey to Palomar Observatory began in 1985 when I joined the team embarking on a 2nd epoch sky survey using the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope to image the northern sky using 14 × 14-inch photographic glass plates. Little did I realize then that discovery of comets, supernovae and asteroids would be a part of my life for the duration of the Second Palomar Observatory Sky Survey. With mentoring from Charles Kowal, Alain Maury and James Schombert I began my searches in 1987 and continued scanning plates until the last night of the survey, June 3, 2000.

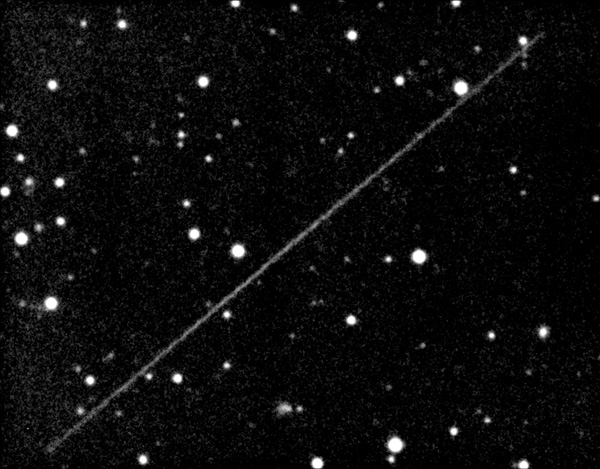

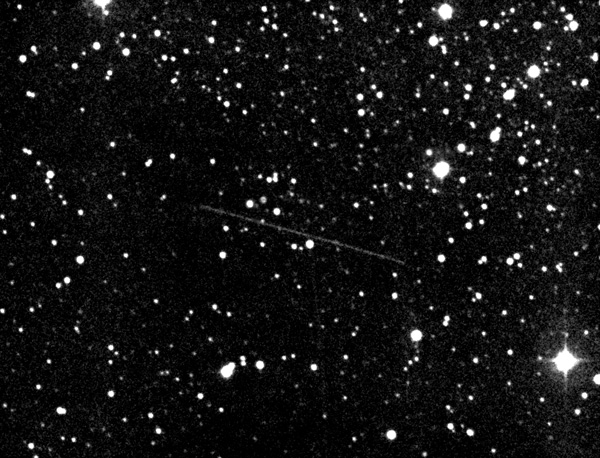

From top to bottom, discovery images of asteroids (12711) Tukmit, (11500) Tomaiyowit, and (9162) Kwiila. (Palomar/Caltech)

It was the asteroids that brought me to the Pauma Band. The discoverer of an asteroid has the privilege to name it, within International Astronomical Union (IAU) guidelines, once the asteroid’s orbit around the Sun is determined. At the time a names committee under the auspices of the IAU’s Central Bureau of Astronomical Telegrams had the authority to accept or decline submitted names and/or citations. It was customary to name Apollo (Earth orbit-crossing) and Amor (Mars orbit-crossing) asteroids for Greek and Roman mythological beings. Half of my discoveries are Apollo asteroids, but by the mid-1990s, most Greco-Roman names were taken. With a life-long interest in Native American history and some familiarity with local Luiseño culture including their ties to Palomar Mountain, I pondered Luiseño names as a way to honor their creation stories and culture. Classical mythological names have traditionally been assigned to Apollo asteroids, therefore I consulted the head of the Central Bureau, Brian Marsden, to propose diverging from precedent. He agreed with the suggestion.

Next, I dove into Luiseño history within reference books at home and at the Escondido Library Pioneer Room. In my reading I discovered that Ed Krupp, Director of Griffith Observatory, had published several articles on Luiseño skylore. Having met him in 1981 in an archeoastronomy class at USC, I contacted him. He graciously sent me two of his articles which proved helpful. From my collection of sources, I selected several possible names from the Luiseño creation stories to be proposed to the tribe hoping for their engagement and approval as I would only proceed with their consent.

My initial contact was in 2002 with the Luiseño/Cupeño Intertribal NAGPRA Coalition LINC Committee which disbanded shortly after I had met with them. They were receptive to the idea and we discussed names at a subsequent meeting. They proposed the name Kwiila which means Black Oak and was one of the First People in their creation story. I proposed Tukmit and Tomaiyovit (Father Sky and Earth Mother, respectively) from their creation story.

It wasn’t until 2008, that I pursued the idea once again. Palomar Observatory’s first Public Affairs Coordinator, Scott Kardel in his own recent communications with the Pauma Band put me in contact with Patricia Dixon, Pauma elder and long-time Palomar College American Indian Studies professor. I wrote an updated proposal. With consent and support by Dixon as well as elders from several Luiseño bands including the Pauma, I submitted the names to the IAU names committee for final approval. Once the names were published in the IAU’s Minor Planet Circulars, we could make a public announcement.

In 2009, under Scott Kardel’s leadership, there was a Luiseño Asteroid-Naming Event at Palomar Observatory. Pauma Chairman, Chris Devers led the group of Pauma participants including several children who drew and painted depictions of Luiseño stories. Representatives from other Luiseño bands also attended. There was a ceremonial blessing, talks and a presentation to the Pauma Band of plaques with images of the three asteroids. A good time for all.

For me personally, I had time to reflect on this journey. While it was a long one spanning over 20 years, it came with the benefit of meeting and interacting with the many who greatly enhanced my life as I learned about the Luiseño people. I hope that I have positively touched their lives even a little bit as they have enriched mine. I even look up at the Milky Way with a new fondness and meaning. I am happy that Iife bestowed on me the opportunity to contribute to the Palomar Observatory and the Pauma Band in helping establish our ongoing relationship which includes sharing our history and perspectives in science and culture to the greater community. For this experience, I will be forever grateful. Thank you.

Reviving the Partnership

By Andy Boden

Following this 2009 precedent most readers will recall the 2022 naming of a novel asteroid discovery in conjunction with and to honor the Pauma Band. The observatory remains grateful to have worked and reinforced partnerships with local indigenous groups on the 2022 asteroid naming.

Preparing for the 2022 event, the original archeoastronomy research papers by longtime friend and colleague Ed Krupp mentioned above came to my attention, and the title of one in particular—“The First Palomar Astronomers” [k05]—was uniquely important for me. “First Astronomers” spoke to me on the importance of recognizing the astronomy practiced by First Peoples in the Palomar area, and the cultural importance this astronomy held for them in their lives. Soon Annie Mejía and I had resolved to feature the First Astronomers perspectives in a digital exhibit on our observatory website, and on our digital kiosks (at Palomar and Caltech/Cahill). Most of the exhibit content was developed by mid-2023, and then coordinating with our Pauma partners we planned a dedication event to commemorate its release—hosted by the Pauma Band at their Tribal Center in May 2024.

Going forward we hope to continue cooperative projects with the Pauma Band and other local indigenous groups, with the goal of highlighting Native American culture to our observatory community and physical and virtual visitors. Hundreds of years before the observatory existed, astronomy practiced by the Luiseño on and around Palomar Mountain served both practical and cultural purposes. This fact evidences an important truth: something deep in our human condition compels us to appreciate our sky with wonder, and to build narratives that help us relate to it—and to each other. That common thread connects what we are fortunate to do every clear night at Palomar with the First Peoples of the area, and calls us to recognize this ‘prior art’ with a sense of respect, humility, and appreciation.

References

- E. C. Krupp (2005) The First Palomar Astronomers, Onward and Upward! Papers in Honor of Clement W. Meighan, Stansbury Publishing, 75–92.

Further Reading

- C. Eller (13 June 2024) Before the Telescope: Palomar's Indigenous Astronomers, Caltech News.

A Docent Workshop at Lick Observatory

By Steve Flanders

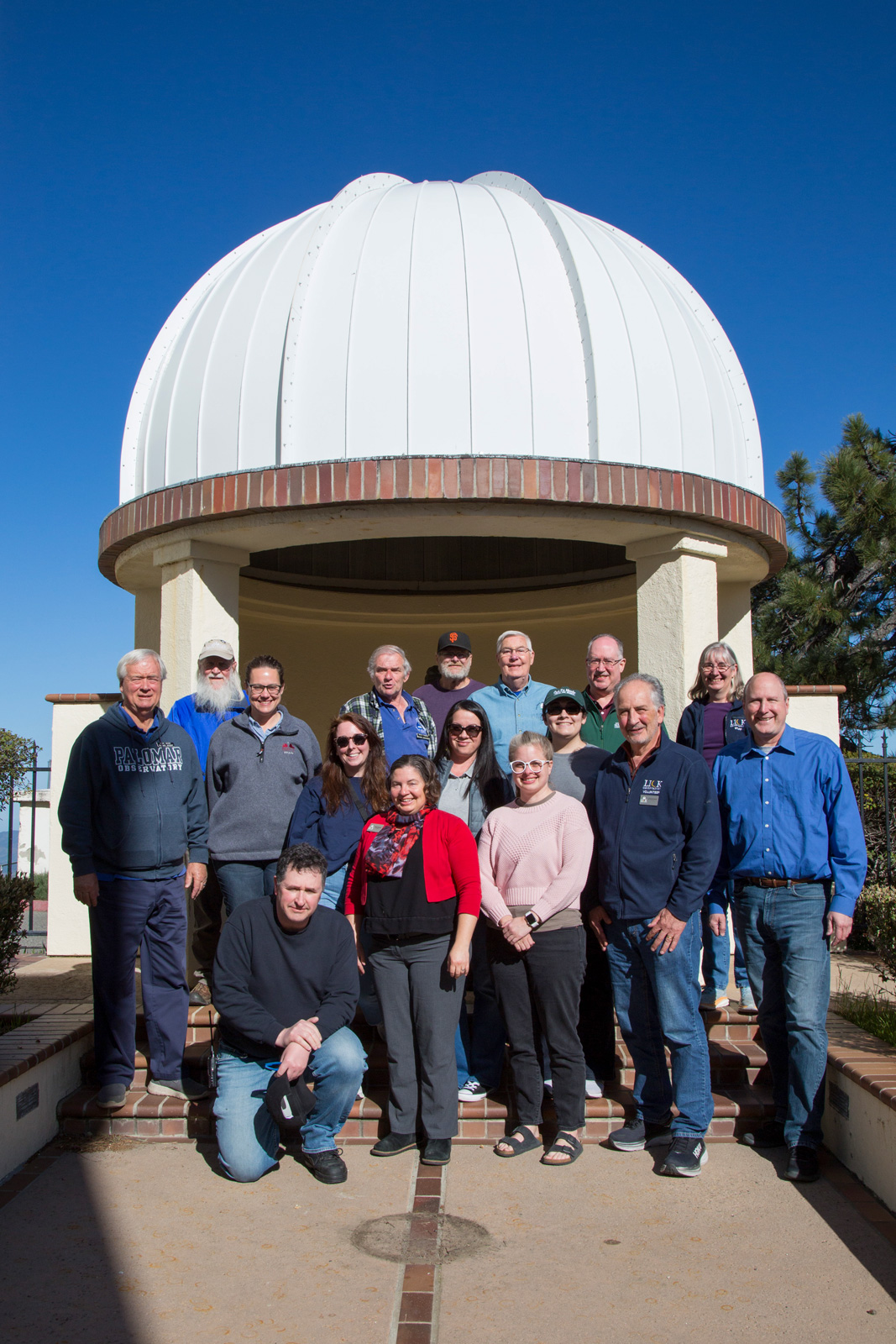

At the end of April this year, I accompanied four Palomar docents on a trip to Lick Observatory on Mt. Hamilton near San José. Docents Kin Searcy, Elvira Hernández, and Deborah and Mark Baker had been invited to attend a three-day workshop sponsored by the newly-formed Alliance of Historic Observatories (AHO, of which Palomar is a founding member) and by the University of California Observatories (UCO).

The event was organized by Matthew Shetrone, Deputy Director of UCO, and by Andy Boden, Deputy Director of Caltech Optical Observatories. Five AHO member organizations sent docent representatives to the workshop with the intent, as Shetrone has written, of:

Sharing the different approaches and solutions [that] might lead to efficiencies and innovations [so that] by sharing our success and challenges we might all excel in our mission.

Or, as Dr. Boden has expressed it, this meeting marks the beginning of a continuing process that will enable:

Docents from different AHO member observatories [to] learn from their peers at sister observatories [and] establish relationships that will be an ongoing resource for our docent communities.

The five historic observatories participating in the workshop were: McDonald, Lick, Yerkes, Mt. Wilson and Palomar Observatories. On the first morning, to get the workshop started, each delegation gave a presentation as a way of introducing its members and providing everyone with a short description of characteristics of the outreach program at the delegation's home institution.

The workshop attendees standing at the memorial to James Lick after lunch on May 1, 2024. (D. Baker)

After lunch, the work of the meeting began with two breakout sessions: one session concerned the issues of budgeting and income; the other served as a forum for the discussion of methods that might be used to improve the volunteer experience.

Then discussions recessed in the late afternoon as members of the observatory’s staff invited the workshop attendees to take part in a walking tour of Lick Observatory. Among Lick’s many notable assets, the 120-inch Shane Telescope with its record of continuing science operations and its historic connection to Palomar was particularly impressive.

Next morning, Tuesday April 30, we spent the first hour soliciting reactions to the walking tour. Among other comments, many people were impressed with how thoroughly the tour demonstrated that “Lick is alive and well.”

During the morning's second hour, we reconvened the two breakout sessions from the previous day. Then, following a break, the subject was changed to focus on the training of docent volunteers, arranged in two parallel sessions—one on training topics in general, the other on management’s view of docent training—followed by a 30-minute group discussion on the same subject.

After lunch, the afternoon began with two breakout sessions. The first of these considered standards of professionalism an institution might set for its volunteers and docents while the people who participated in the parallel session addressed the question of how an institution might help its volunteers when dealing with the public on matters of controversy.

Late in the afternoon, we held a breakout session and then a group discussion on the subjects of inspiration and education.

After dinner, the observatory's support astronomers held a star party using the Great 36-inch Refractor and the Nichols 40-inch Reflector. The view we had of the starburst galaxy NGC 3034 was especially memorable.

The final day of the workshop, Wednesday May 1, began after breakfast when Shetrone opened the first hour of the morning by soliciting comments regarding the previous evening's star party. Everyone commented on the remarkable quality of the images produced by both telescopes.

The final topic of the day concerned guest safety, an important item we considered during a breakout session before lunch and in a group discussion in the afternoon. The workshop closed with an exchange of shared comments and general reactions.

The members of Palomar's delegation shared one key observation: for reasons that may be obvious, our outreach program is quite unlike the programs in place at the other four observatories. All AHO member institutions have their own unique priorities, business models, and operational constraints. Palomar is no exception among AHO members: the contours of Palomar’s public program are informed by Caltech’s emphasis on the observatory’s research mission.

Even if Palomar’s public engagement model is different from sister observatories there is value in hearing how peer AHO institutions approach similar public engagement objectives. We can always learn important lessons from stepping back and considering different perspectives on programs and challenges we all share.

With that, I’ll conclude by pointing to an item on the AHO website, one of four objectives that follow their mission statement. The AHO seeks to:

Tell our stories as a model for how the observatories inspire people around the world to foster greater literacy in science.

Over many years, a dedicated, knowledgeable, and experienced group of professionals has come together on this mountain. These people are deeply committed to Palomar Observatory, to its continuing value to science, and to the stories they tell and retell about this place to the many guests who visit us each year.

Andromeda Exhibit Update

By Andy Boden

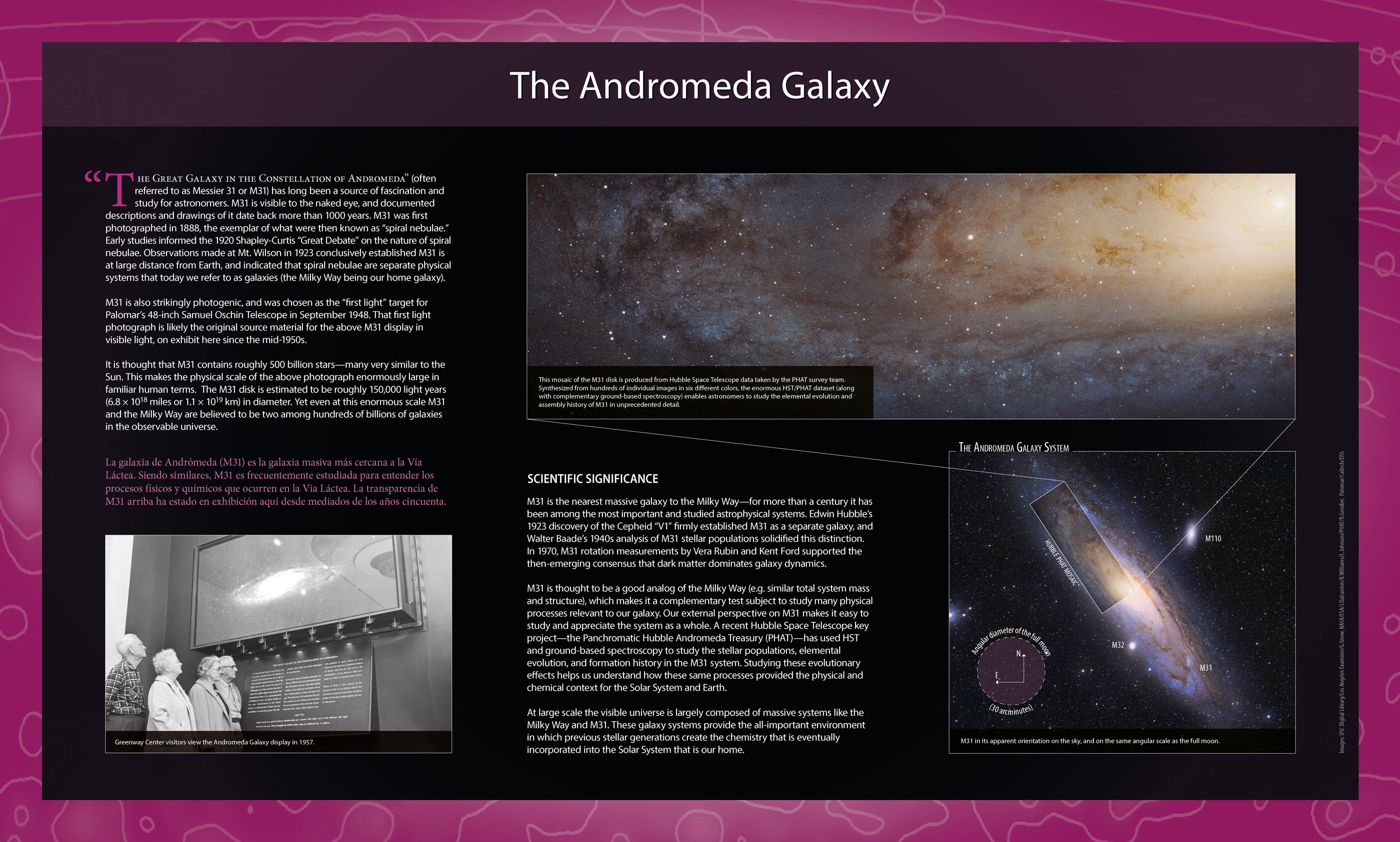

If you have recently visited our Palomar Museum space (Greenway Visitor Center) you may have seen some updated description material for the large Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31) lightbox at the southeast end of the exhibit hall. Revised as part of our 75 Anniversary activity, the new supporting text updates framing context for the M31 exhibit.

Greenway Center visitors view the Andromeda Galaxy display in 1957. (USC Digital Library/LA Examiner/G. Snow).

New label for Andromeda display, now matching the style of other museum graphics. (Palomar/Caltech)

The Greenway Center is named in honor of the son of Caltech benefactor Kate Bruce Ricketts. The structure was built late in the original Palomar Observatory construction arc; historical materials indicate 1939 – 1940 for building construction. Remarkably the museum exhibit hall seems to have remained undeveloped until the mid-1950s when a gift from Mrs. Ricketts supported opening the space to visitors with a collection of astronomical photographs taken at Palomar. Among these initial displays was the M31 lightbox transparency; old photographs evidence the M31 lightbox in the museum space by 1957. So the M31 lightbox is our last remaining exhibit from the Greenway Center’s initial 1950s era. Separately museum records [d52] suggest it is likely that the M31 transparency is derived from the first light photographic plate for the 48-inch Schmidt (now the Samuel Oschin Telescope) in September 1948.

Fast forward to January 2023, when Annie Mejía and I resolved to update the contextual description for the M31 lightbox exhibit to something more modern and scientifically informative. M31 is of course a nearby peer galaxy to our own Milky Way, and the nearest external massive galaxy to Earth. M31 isn’t just strikingly photogenic, it’s astrophysically important as a Milky Way analog—and due to its proximity and our external perspective on it M31 has long been thought of as the ideal test system to study many processes that have shaped our own galaxy. As such M31 remains a popular and important astronomical subject for both amateur and professional astronomers alike.

Our update incorporates imaging from the Hubble Space Telescope PHAT (Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury [d12]) program. PHAT illustrates a modern and powerful approach to M31 systematic study. PHAT imaged a large portion of the M31 stellar disk in six colors with the WFC3 and ACS cameras. The survey was completed in 2015, and has been the benchmark M31 dataset ever since—supporting extensive subsequent study. From 2012 to 2024 the PHAT survey has contributed to more than 200 research papers (roughly half of them peer-reviewed). My personal favorite is Gregersen et al 2015 [g15] which presents clear evidence of elemental evolution over the inner 20kpc of the M31 disk (processed/heavy element abundance decreasing with increasing M31 galactic radius). The result illustrates how we believe elemental enrichment proceeds in galactic disks over time, leading to the incorporation of processed materials in star/planet systems like our own—and enabling the chemistry that makes life on Earth possible.

References

- A. J. Deutsch (16 October 1952) Report on the Palomar Museum, Caltech Archives, Papers of Lee A. DuBridge, 1932-1986, 25.15.

- J. J. Dalcanton et al (June 2012) The Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury. ApJS, 200(2):18–54.

- D. Gregersen et al (December 2015) Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury XII: Mapping Stellar Metalicity Distributions in M31. AJ, 150(6):189–200.

Questions? We've answered many common visiting, media, and academic questions in our public FAQ page.

Please share your feedback on this page at the

COO Feedback portal.

Big Eye 18-1

Last updated: 15 June 2024 JEM/AFB/SBF/ACM