|

|

|

The 48-inch (1.2-meter) Samuel Oschin Telescope

Palomar Observatory’s 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope is one of the most productive survey telescopes ever built with a dozen completed surveys since the 1950s. The wide-field imaging capabilities of this telescope (it has a usable field hundreds of times larger than that of the 200-inch Hale Telescope) makes it ideal for conducting systematic surveys of the sky. In recent years, the Samuel Oschin Telescope has been used to scan large regions of the sky to search for transient events—objects that change apparent brightness and/or position—such as fast-moving Solar System objects, variable/pulsating stars, flares, novae, supernovae, gamma-ray bursts and other stellar explosions. It currently operates robotically, scanning the skies nightly and returning a wealth of astronomical data.

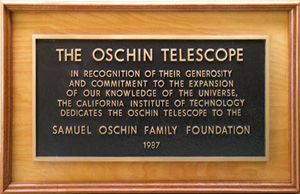

The telescope was rededicated as the Samuel Oschin Telescope in 1987, in recognition of the prominent adventurer, entrepreneur, and philantropist’s passion for astronomy and generous support to the Observatory.

The information on this page is intended for the public. Observer information for the Samuel Oschin Telescope can be found on the corresponding observer page.

- Operations

- A survey instrument

- Construction and upgrades

- Surveys completed

- Notable discoveries and scientific legacy

- Graphical timeline

- Virtual tour

- Media

Contents

Operations

The Samuel Oschin Telescope has an advanced robotic control system—the telescope typically operates with no one physically at the dome. It begins its routine by taking calibration images during the afternoon. Weather permitting, the dome opens and the telescope begins observing at astronomical twilight. Observation targets and schedules are generally planned out in advance, but the scheduler software is flexible enough to allow for new target submissions on short notice. Software decides the optimal order in which the observations are carried out in order to minimize slewing.

The Samuel Oschin Telescope produces hundreds of images a night. At the end of each observation, the data collected is beamed out by microwave via the High Performance Wireless Research and Education Network (HPWREN) to the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at Caltech for real-time processing and archiving. Any interesting candidates are then followed up with other facilities, including the Palomar 60- and 200-inch telescopes for both imaging and spectroscopy.

A Survey Instrument

A Schmidt telescope is an instrument used to obtain sharp, wide-field images of the sky with a single exposure. Instead of the usual parabolic mirror of a reflecting telescope, a Schmidt contains a spherical primary mirror and a weakly curved aspheric lens, known as a corrector. The combination of these two optical elements correct for off-axis aberrations present in conventional telescopes that prevent them from properly focusing light incoming at an angle. The result is an instrument capable of efficiently photographing large areas of the sky with pinpoint images throughout. Some people refer to the Schmidt design as a Schmidt camera because an observer cannot in fact look through it.

The 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope is one of the largest Schmidt cameras ever built, has a 48-inch (1.2-meter) aperture with a glass corrector plate and a 72-inch (1.8-meter) f/2.5 mirror. It was originally designed to use 14-inch (35.5-cm) square photographic plates, each covering 36 square degrees of sky, but was upgraded in 2000 to use electronic detectors. To date, four CCD cameras have been installed in the telescope.

Construction and Upgrades

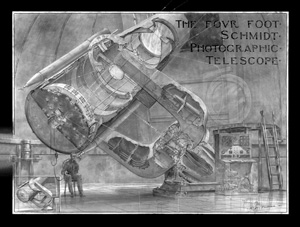

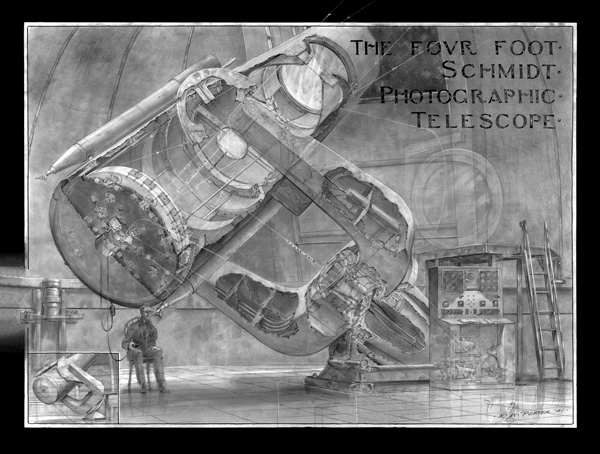

Cutaway drawing of the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope by Russell W. Porter. The 48-inch corrector lens is at the top of the tube. Halfway down the tube is a photographic plateholder—electronic detectors have since replaced plates in this instrument. The 72-inch spherical mirror is at the bottom of the tube. An observer is shown looking through one of the auxiliary 10-inch refracting guidescopes. (Palomar/Caltech/Caltech Archives)

The Schmidt telescope was invented in 1930 by optician Bernhard Schmidt at the Hamburg Observatory, Germany. Palomar was one of the first observatories in the world to utilize this new technology, which enabled astronomers to survey the sky. Given the success of the 18-inch (0.46-meter) Schmidt telescope during the 1930s, resources for building the larger 48-inch Schmidt were committed in 1937.

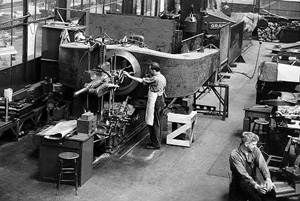

Using funds and technology from the 200-inch Hale Telescope, work on the 48-inch Schmidt began in 1938. Corning Glass Works of New York casted the main mirror for the telescope. The mirror and the refractive corrector plate were figured under the direction of Don Hendrix of the Mount Wilson optical shop at Carnegie, just blocks from the Caltech campus, while the mount was fabricated at the Caltech instrument shop. The dome to house the 48-inch was mostly finished by 1939.

After delays due to World War II, the 48-inch was completed in 1948 and for years it was the largest Schmidt telescope in the world. It took its first official photograph in September 1948. The 48-inch began, a year later, the first in a long list of sucessful and consequential surveys completed during its prolific operational life.

In the mid-1980s, the 48-inch Schmidt was upgraded with a new achromatic corrector and autoguiding. It was named the Samuel Oschin Telescope in 1987 to recognize a generous donation to Palomar Observatory by the Oschin family—funds were used for POSS II, adaptive optics on the Hale Telescope, and new electronic cameras.

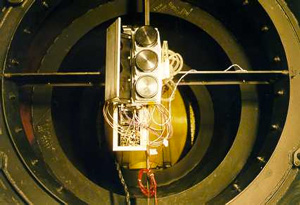

Between 2000 and 2001, the Samuel Oschin Telescope was modified for robotic operation and the original photographic equipment was replaced with its first CCD camera. JPL's NEAT camera consisted of three separate 4080×4080 arrays oriented north-south—each 3-array image covered about 3.75 square degrees. The telescope control system was upgraded to enable automatic operation and continuous, automatic survey of sky every clear night.

Two years later, the NEAT camera was replaced by Yale University’s QUEST 2 camera—a 112-CCD, 161-megapixel camera, one of the world’s largest. It covered an area of 4.6×3.6 degrees on the sky with an active area of 9.6 square degrees. The telescope and camera operated in two distinct modes: point and track (the telescope is pointed to an area of the sky and takes a relatively short exposure), and drift scan (the telescope is parked at a fixed position as the Earth's rotation causes a strip of sky to slowly drift past it).

The PTF camera—a 96-megapixel CCD mosaic camera formerly known as the CFH12K camera was installed in 2008. It was used for high resolution wide field imaging, observing a 7.8 square degree field every 90 seconds.

The current camera installed on the Samuel Oschin Telescope is the ZTF camera, with sixteen 6k×6k CCDs that cover 47 square degrees of sky per image. This camera has the world's widest field of view on a telescope larger than a half meter—each image covers 247 times the area of the full moon—which enables a full scan of the northern visible sky every three nights. ZTF's extremely wide field and fast readout electronics enable a survey more than an order of magnitude faster than that of PTF. The goal is to search and catalog rare and exotic transients and drive novel studies of supernovae, variable stars, binaries, AGN, and asteroids. The ZTF camera saw first light in November 2017.

Surveys Completed by the Samuel Oschin Telescope

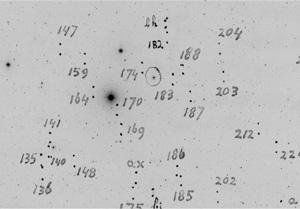

(1949 – 1958) The National Geographic Society – Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS I): POSS I made the first comprehensive photographic survey of the entire northern sky with 14-inch square photographic plates in two colors: Blue (103aO) and Red (103aF). It became the standard library reference for every major observatory worldwide. The survey extended to the southern sky in the 1970s with the UK Schmidt in Australia (a virtual copy of the Palomar Schmidt) and a smaller ESO Schmidt in Chile. POSS I was used to produce the first major catalog of galaxy clusters which allowed astronomers to map the structure of the universe for the first time. Additionally, new globular clusters, dwarf galaxy companions of our the Milky Way, merging and interacting galaxies, and the first optical identifications of radio sources and quasars were made using POSS I.

The Rosette Nebula (NGC 2237) in Monoceros—a composite from two images taken with the Samuel Oschin Telescope as a part of the Second Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS II). (Palomar/Caltech/DSS)

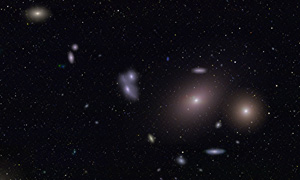

The Big Picture is a single continuous digital sky image derived from the Palomar-Quest digital sky survey. It is the largest astronomical photograph ever produced—on display as a 152 ft (43.3 m) long by 20 ft (6 m) high wall at Griffith Observatory. This segment shows the core of the Virgo cluster of galaxies. The "Markarian's Chain" of galaxies dominates the picture, with the giant elliptical galaxy M87 in the bottom left. (The Palomar-Quest Team/Caltech)

(1959 – 1975) Supernova Searches: 178 supernovae were discovered in monthly surveys. Many more were discovered on old plates from POSS I.

(1960) The Palomar-Leiden Survey: discovered more than 2,000 asteroids (1,800 with orbital information) in eleven nights. This number was increased to 2,400 including 19 Trojans after further analysis of the plates.

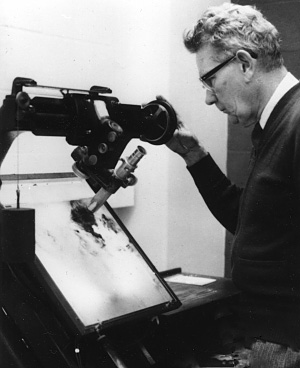

(1962 – 1971) The Palomar Proper Motion Survey: a photographic survey to determine the proper motions of stars—their apparent motion across the sky. This survey discovered many of the stars closest to the Solar System and provided important context for studies of Galactic structure.

(1971) The First Palomar-Leiden Trojan Survey: discovered approximately 500 asteroids including 4 Trojans in nine nights.

(1973) The Second Palomar-Leiden Trojan Survey: discovered another 1,200 asteroids including 18 Trojans in eight nights.

(1977) The Third Palomar-Leiden Trojan Survey: discovered an additional 1,400 asteroids including 24 Trojans in seven nights.

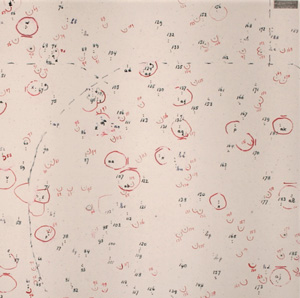

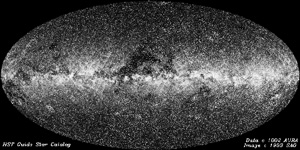

(1982 – 1984) The Quick V Survey: this survey was used to form the northern half of Hubble Space Telescope’s Guide Star Catalog. Included within it are the positions and brightnesses for approximately 19 million stars and other objects.

(1985 – 2000) The Second Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS II): POSS II encompassed 897 survey quality plates in each of 3 colors. It formed the basis for the STScI Digitized Sky Survey (DSS), the second Hubble Space Telescope Guide Star Catalog, and the United States Naval Observatory astrometric and photometric catalogs, all of which contain over 1 billion stars and over 50 million galaxies. POSS II and its digitized version (DPOSS) resulted in the identification of tens of thousands of galaxy clusters, hundreds of supernovae and quasars, and dozens of comets and asteroids. It was the largest such catalog ever.

(2001 – 2007) The Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT) program: JPL’s NEAT survey was the first electronic and automated survey with the Samuel Oschin Telescope. Upgrades enabled continuous, automatic survey of sky for Solar System moving objects, variable stars, and transient events. At Palomar, NEAT discovered close to 300 near-Earth asteroids and 13 comets.

(2003 – 2008) The Quasar Equatorial Survey Team (QUEST): this survey focused on searching for variable stars, quasars, gravitational lenses, and distant supernovae. Palomar-QUEST pioneered the automated classification of transients by processing data in real-time.

(2009 – 2012) The Palomar Transient Factory (PTF): was a fully-automated, wide-field survey designed to search for optical transient and variable sources. It included a wide-field camera, an automated real-time data reduction pipeline, a dedicated photometric follow-up telescope, and a full archive of all detected sources. PTF discovered tens of thousands of new transient sources including thousands of new supernovae, novae and cataclysmic variable stars, flaring young stars, and the first-ever detection of a planet orbiting a young star in Orion.

Mapping the sky with the Palomar telescopes. Duration: 6:20 min. (Palomar/Caltech)

(2013 – 2017) The intermediate Palomar Transient Factory (iPTF): was a fully-automated, wide-field survey for a systematic exploration of the optical transient sky. This project was built upon the legacy of the Palomar Transient Factory (PTF). With improved software for data reduction and source classification, the project achieved significant successes in the early discovery and rapid follow-up studies of transient sources. In 2017, iPTF transitioned to the Zwicky Transient Factory (ZTF).

(2018 – present) The Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF): Armed with the ZTF camera, the Oschin Telescope robotically scans the sky every clear night looking for transients. When transient sources are detected, the companion 60-inch telescope is robotically tasked to measure source colors to perform rough classification and initial assessment. During the first five years of operation ZTF discovered and classified over 8000 supernovae, including over 3000 Type Ia events; hundreds of near-Earth asteroids, and tens of rare transients like tidal disruption events when a star is violently ripped apart by the gravity of a black hole.

Notable Discoveries and Scientific Legacy

This long-exposure Hubble Space Telescope image of massive galaxy cluster Abell 2744 is the deepest ever made of any cluster of galaxies. Abell 2744, located in the constellation Sculptor, appears in the foreground of this image. It contains several hundred galaxies as they looked 3.5 billion years ago. (NASA/ESA/STScI)

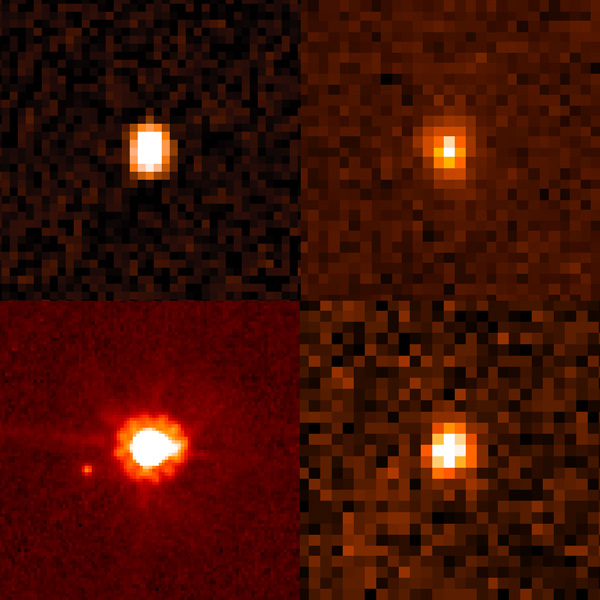

Four of the transneptunian objects discovered with the Samuel Oschin Telescope as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Clockwise, from top left: Quaoar, Sedna, Orcus, and Eris/Dysnomia. (NASA/ESA/M.Brown/Caltech)

Large-Scale Structure

One of the most important aspects of the survey work performed by instruments such as the Samuel Oschin Telescope is the ability to use resulting data in multiple ways and over time. One such derivative work from the 1950s POSS I survey is the Abell catalog of galaxy clusters—George Abell's collection of the richest and densest galaxy clusters found on the POSS I plates identified by a well-defined set of selection criteria. With 2,712 clusters (an additional 1,361 southern sky clusters were added in 1989), the Abell catalog reflects the large-scale structure of the Universe as traced by galaxy clusters. Galaxy clusters are the largest gravitationally-bound structures in the Universe, and their enormous mass can be used to study more distant objects through gravitational lensing. Today studies of the most distant objects in the Universe (e.g. the Hubble Frontier Fields program) use the galaxy clusters cataloged by POSS I and George Abell to give us some of our deepest views and insights into the early Universe.

Dwarf Planets

Between 2001 and 2007, first using photographic plates and later the NEAT and QUEST 2 cameras, Mike Brown and his team discovered over a dozen transneptunian objects including Quaoar, Sedna, Orcus, and Eris with its moon Dysnomia. Eris, the largest and most notable, is about one quarter more massive than Pluto. These pivotal discoveries, arguably some of the most important in Solar System astronomy in recent years, resulted in the revision of the definition of a planet by the Astronomical International Union and the designation of Pluto and other smaller bodies as dwarf planets.

Cosmic Explosions

The Samuel Oschin Telescope is instrumental in the study of cosmic explosions—supernovae, hypernovae, and gamma-ray bursts—both as discoveries and follow-up observations. Some of the exploding objects discovered in the past few years have made science news headlines because of their exotic and even unique nature. These objects offer astronomers exciting new opportunities to better understand the evolution of massive stars and the richness of their environments. Some of the most notable are:

- The gamma-ray burst GRB 021004, observed just 9 minutes after the burst was detected by the satellite HETE-2 in 2002.

- The super-luminous supernova SN2005gj discovered independently by the Samuel Oschin Telescope and the Nearby Supernova Factory (LBL) in 2005, later explained as a possible result of an exotic object called quark star.

- A "new class of hydrogen-poor super-luminous stellar explosions"—bright, blue and among the most luminous supernovae in the cosmos. Four objects of this kind were discovered by PTF in 2011. Their true nature remains unknown, but they could involve a massive pulsating star (about 90–130 times the mass of the Sun) as progenitor or a supernova that leaves behind a magnetar—a rapidly rotating, compact object with a strong magnetic field. These newly discovered supernovae live in dim, small galaxies called dwarf galaxies.

- SN2010mc, also known as PTF10tel, was predicted based on the progenitor undergoing a precursor eruption more than a month before the supernova explosion itself.

- SN2011fe, also known as PTF11kly, was the "brightest and closest stellar explosion seen from Earth in 25 years” as of 2011. The proximity of this type Ia supernova and its early discovery made possible for astronomers to confirm the progenitor system and have the most detailed picture yet of how these explosions occur. Supernovae type Ia are used to measure the expansion of the Universe because they are standard candles—their intrinsic brightness is well known. Understanding these systems in detail is essential in the measurement of extragalactic distances and the cosmic expansion rate.

Graphical Timeline

Samuel Oschin Telescope graphical timeline ( go to expanded timeline). Time starts in 1930 and flows to the right; use the scroll bar to reach the 2010s. Each column corresponds to a decade, vertical lines indicate years. Darker background shows when the telescope was operational. Each event is shown as a bar whose width indicates time span. Hovering with mouse over an event will bring up a short explanation. Hint: use the keyboard shortcuts (no shift) control/command + to zoom in, control/command − to zoom out, and control/command 0 to reset.

Virtual Tour

This bilingual, high-resolution tour embeds relevant information, images, and video of the Samuel Oschin Telescope. We recommend viewing the virtual tour on a desktop or laptop in fullscreen mode using the icon in the control bar. While it is possible to view the tour in smaller screens (e.g., large tablets), we suggest using the "lite" version of the tour for screens narrower than 700px (e.g, smaller tablets and smartphones). The lite tour is also VR-enabled, but lacks many of the features found in the full version of the tour. Click here to load the full tour.

Bilingual, annotated tour of the Samuel Oschin Telescope and its dome, desktop version. (Palomar/Caltech/A.Mejía)

Bilingual, annotated tour of the Samuel Oschin Telescope and its dome, mobile version. (Palomar/Caltech/A.Mejía)

Media

The 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope (2020)

Video introducing the history and science of the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope. Duration: 2:18 minutes. (Palomar/Caltech)

For more images of the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope, please visit the media section.

Questions? We've answered many common visiting, media, and academic questions in our public FAQ page.

Please share your feedback on this page at the

COO Feedback portal.

Samuel Oschin Telescope / v 1.0.14

Last updated: 14 March 2024 ACM

|

|

|