|

|

|

The 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope

Dedicated in 1948 and the largest effective telescope in the world until 1993, the 200-inch Hale Telescope is a workhorse of modern astronomy and contributes to a wide range of astronomical research including Solar System studies, the search for extrasolar planets, stellar population and evolution analysis, and the characterization of remote galaxies. This extraordinary instrument was the vision of astronomer and Caltech founder George Ellery Hale—the man behind the largest telescopes in the world at the beginning of the 20th century. Hale vigorously pursued funding to build the 200-inch Telescope and eventually secured the sponsorship of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1928. All aspects of building such a large and precise instrument required innovative methods and revolutionary technology, which has lead some to consider it the “moon shot” of the 1930s and 40s.

The information on this page is intended for the public. Observer information for the Hale Telescope can be found on the corresponding observer page.

- Operations

- 200-inch mirror and foci

- Facility instruments

- Telescope mount and dome

- Construction

- Notable discoveries and scientific legacy

- Extragalactic distance measurements and cosmic expansion

- Stellar populations and evolution

- Quasars and active galactic nuclei

- Technological innovation

- Graphical timeline

- Virtual tour

- Media

Contents

Operations

The Hale Telescope is operated by a telescope operator from the relative comfort of a control room within the telescope dome. Astronomers have the option of observing on site or remotely from their academic institutions. Although additional processing is often needed, astronomers see their results in real-time on a computer screen. For a brief explanation of the research and observations being undertaken on the Hale Telescope during the current week, please follow this link.

The 200-inch Mirror and Foci

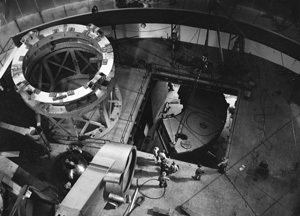

The 200-inch mirror is removed from the telescope truss approximately every two years for aluminum recoating. Duration: 3:06 minutes. (Palomar/Caltech)

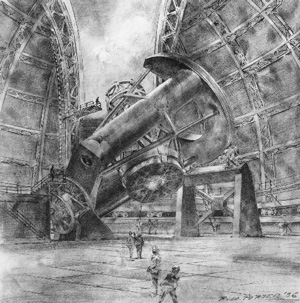

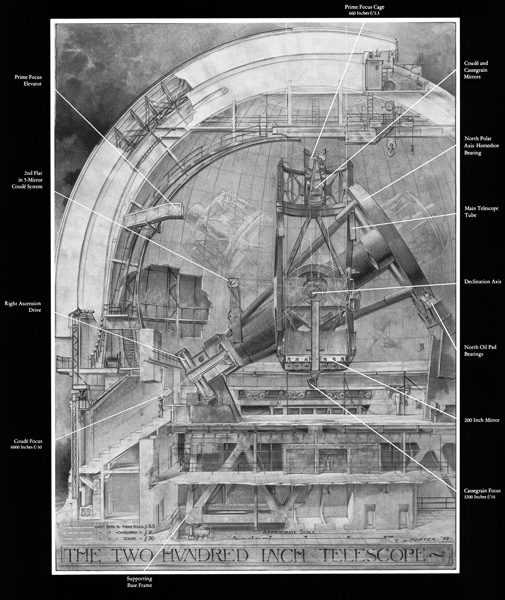

Meridian cross-sectional drawing of the 200-inch Hale Telescope and dome by Russell W. Porter. White lines indicate the light path for an observer or instruments placed at the prime focus (top of the telescope) and at the coudé focus (lower left along the telescope’s polar axis). The labels identify the telescope’s main features. (Palomar/Caltech/Caltech Archives)

The Hale Telescope is a reflector, that is, a telescope whose primary optical element is a curved mirror—there are no lenses in the telescope itself. The Hale's primary mirror is a 200-inch (5.1-meter) in diameter Pyrex disk that weighs 14.5 tons (13 tonnes). Its polished surface, covered with a thin layer of aluminum, is concave. The mirror's thickness varies between 19 ⅝ inches (49.8 cm) at the center and 23 ½ inches (59.7 cm) at the outer edge.

The primary mirror's area, about 31,000 square inches or 20 square meters, acts as a giant pupil that collects light from the Universe. Because the mirror is a paraboloid (f/3.3, focal length 660 inches or 16.76 meters), light comes to a focus near the top of the telescope at what is known as the prime focus. A camera or scientific instrument can be placed at prime focus, or a secondary mirror to reflect the light back down through a hole in the primary mirror to what is known as the Cassegrain focus (f/16, focal length 3,200 inches or 81.3 meters). Two additional light paths are also possible—by using additional mirrors, light can be directed into the coudé focus (f/30, focal length 6,000 inches or 152 meters) or to an instrument in the east arm of the telescope.

Facility Instruments

The Hale Telescope is used every night for astronomical research thanks to a modern and evolving instrument suite. Hale Telescope instruments provide a wide range of imaging and spectroscopic capabilities in the optical and near-infrared parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. A significant fraction of Hale science activity is focused on spectroscopy—dividing starlight into its constituent colors. But Hale instrumentation also emphasizes adaptive optics capabilities that correct for distortions caused by Earth’s atmosphere—known as seeing, what makes stars twinkle—to deliver sharp images comparable to those produced by space telescopes from a ground-based facility.

The Hale's seeing-limited imaging instruments include two wide-field cameras: the Wafer-scale imager for Palomar (WaSP) in the optical and the Wide-field Infrared Camera (WIRC) in the infrared, both mounted at the prime focus of the telescope and covering 24 and 8.9 arcminutes across, respectively. The high-speed CHIMERA imager, also mounting at the prime focus, can even generate video-like data and is used to observe rapidly changing astronomical objects. At Cassegrain focus, the Cosmic Web Imager (CWI) is an imaging spectrograph (integral-field unit) that images over a range of wavelengths simultaneously. The traditional single-object spectrographs are the newly-commissioned Next Generation Palomar Spectrograph (NGPS) and the infrared Triple Spectrograph (TripleSpec), both also install at the Cassegrain focus.

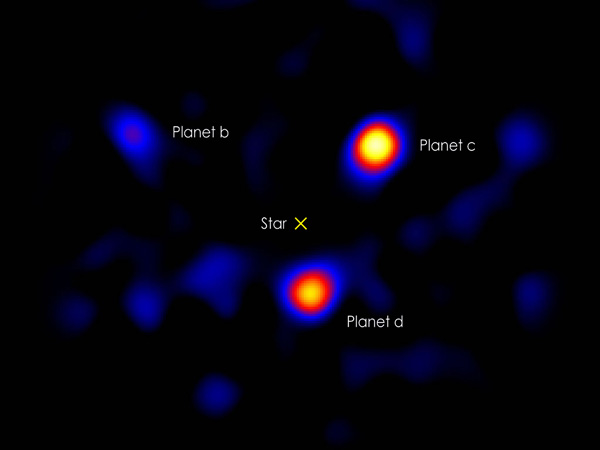

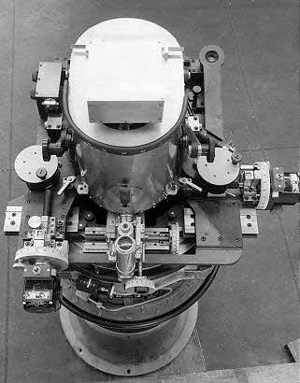

PALM-3000 is the facility adaptive optics system for the Hale Telescope. The heart of the system is a deformable mirror with 3388 actuators that rapidly change the mirror shape. The reflective surface is adjusted in real-time, up to 2000 times a second, to correct for atmospheric distortions and refocus starlight into sharp images. PALM-3000 brings the optical power of the Hale Telescope closer to its diffraction limit by producing images typically 10–20 times sharper than seeing-limited instruments, when sufficiently bright natural guide stars are within the instrument field of regard. It works in conjunction with other image-sharpening devices, including the Palomar High Angular Resolution Observer (PHARO) and the Palomar Radial Velocity Instrument (PARVI). The ability to directly obtain spectra of extrasolar planet atmospheres is one of the many exciting uses of the PALM-3000 + PARVI combination.

Palomar’s newest initiative is SIGHT, an adaptive optics system that will integrate with the Hale Telescope to provide seeing improvement to a range of optical-to-infrared wavelengths at any location on the sky. SIGHT is expected to enter routine science operation within the next couple of years.

Telescope Mount and Dome

Video introducing the design and engineering of Hale Telescope. Duration: 2:51 minutes. (Palomar/Caltech)

The 200-inch mirror and instruments are supported by a steel equatorial mount, which allows for east-west and north-south motion. Moving this 530-ton (481-tonne) telescope must be done precisely if astronomical observations are to be possible at all. For slewing (rapid movement) it uses two small motors: a 3-hp motor for right ascension and a 1-hp motor for declination. For tracking (keeping up with Earth’s rotation during long exposures) it is moved by a 1-hp step motor—this replaced the original 1⁄12-hp tracking motor after almost 65 years of continual use. The Hale Telescope is kept in perfect balance. As such, when instruments are changed the balance of the telescope must be adjusted.

The piers for the Hale Telescope are anchored to the bedrock 22 feet (6.7 meters) below, while the dome supports go about 7 feet (2.1 meters) into the overlying granite. The dome is 135 feet (41 meters) tall and 137 feet (42 meters) in diameter. It is a remarkable coincidence that these dimensions are similar to those of the Pantheon in Rome. The architecture of the dome is discussed in the architecture section.

The rotating part of the dome weighs approximately 1,000 tons (900 tonnes), with a plate steel exterior and aluminum panel interior, separated by four feet (1.2 meters) to allow for an insulating layer of air. Two 125-ton (113-tonne) shutters cover the opening and slide open at night to allow light through the slit and into the telescope. The top section of the dome rotates on two circular rails, riding on 32 carriages each with four wheels. One rotation takes about 4 minutes. Rotation of the dome is driven by four 7.5 horsepower motors (30 hp total).

Construction of the Hale Telescope

Hale dome construction slideshow: 37 images and 1 video. Click ► to start. Use < or > to reverse or advance one slide, or the progress dots to jump slides. Click any image to enlarge and on some captions for further context. The slideshow will pause for videos.

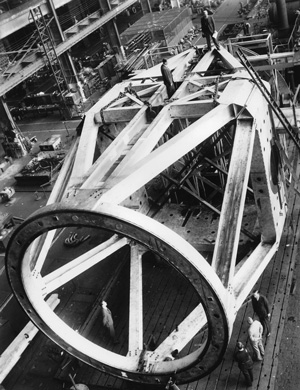

Preparations for the Observatory site began in 1935. Building of the Hale Telescope dome took place between 1936 and 1939 under the watchful eye of superintendent of construction Byron Hill. The dome was designed by the multi-talented technical illustrator Russell W. Porter and engineered by Mark Serrurier, Romeo Martel, and Theodore von Kármán at Caltech. Consolidated Steel of Los Angeles assembled the steel support structure and dome.

The overall design of the 200-inch Hale Telescope is attributed to Porter and Francis Pease, while engineering of its various aspects to Serrurier, Sinclair Smith, Bruce Rule and others at Caltech, and Rein Kroon of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. The construction of the telescope began in 1936. Its components were fabricated primarily at the Westinghouse South Philadelphia plant and then shipped by boat through the Panama Canal to San Diego and trucked to Palomar Mountain for assembly inside the dome. The first telescope parts arrived at Palomar in 1938 and construction was finished in 1939.

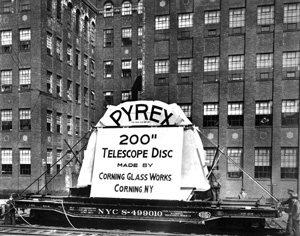

The basic structure of the telescope was completed long before its 200-inch mirror was ready. Astronomers wanted to make the mirror out of a material that would have minimal expansion or contraction with changes in temperature. Initially General Electric was hired to fabricate a 200-inch disk made out of quartz. Just over 600,000 dollars later, that idea was abandoned. The man behind the project, George E. Hale, approached the Corning Glass Works of New York with a proposal to instead cast the 200-inch mirror out of a glass blend called Pyrex. The Corning mirror project was performed under the direction of George McCauley. It took a month to melt the glass needed to cast the mirror.

A failed attempt to cast the mirror disk took place on March 25, 1934—this first disk is on display at the Corning Museum of Glass in New York. A second disk was cast on December 2, 1934. The disk remained in the oven at pouring temperature for just over a month and then was gradually cooled over a period of ten months. McCauley personally checked on the cooling operation daily. For more on the pouring and casting of the 200-inch mirror, please visit the Corning Museum of Glass page titled Mirror to Discovery.

On March 26, 1936, the mirror blank began its 16-day trip by rail from Corning to the Caltech optical shop in Pasadena. The telescope project captured the public’s imagination, and all across the country thousands of people lined the train tracks to watch it pass.

Under the direction of John A. Anderson and Marcus H. Brown at Caltech, the mirror disk was ground and figured into the proper shape. It began as a 20-ton (18-tonne) disk and finished at 14.5 tons (13 tonnes). Including the delays from World War II, the disk was in the optical shop for 11 ½ years.

The mirror finally arrived at Palomar on November 19, 1947. It was transported on the back of a flatbed truck with two additional trucks behind it pushing it up highway S-6 (South Grade Road, then called the “Highway to the Stars”) and to the Observatory site.

The mirror still had to have its performance tested in the telescope. The testing was done by photographing a bright star with the un-aluminized mirror through the Hartmann screen at the top of the telescope. There was a long process of additional polishing, testing and adjustment of the mirror supports. At this point the mirror had the proper shape, but no reflective coating on its surface. A thin layer of aluminum was added in the large chamber that sits on the dome floor.

While not quite completed, the 200-inch was dedicated as the Hale Telescope on June 3, 1948. The telescope was designed for photographic work, all of which was initially done on glass photographic plates. The first “official” photos were taken by Edwin Hubble on January 26, 1949. It was not until November 1949—21 years into the project—that astronomers were finally able to begin research.

The Universe in Color: the first "natural color" deep-sky photographs slideshow, 26 images. Click ► to start. Use < or > to reverse or advance one slide, or the progress dots to jump slides. Click any image to enlarge and on some captions for further context.

Notable Discoveries and Scientific Legacy

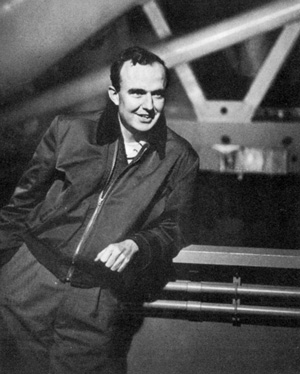

In 1963, Caltech astronomer Maarten Schmidt used the Hale Telescope to obtain the spectrum—the characteristic distribution of light by wavelength or color—of a bright star-like radio source known as 3C 273. The features in 3C 273’s unusual spectrum were greatly redshifted due to the expansion of the Universe. Located billions of light-years away, 3C 273 had to possess an extraordinary luminosity, about a hundred times that of the typical galaxy. (Palomar/Caltech)

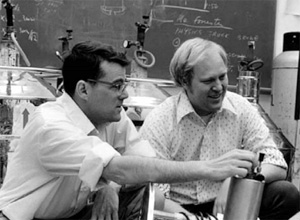

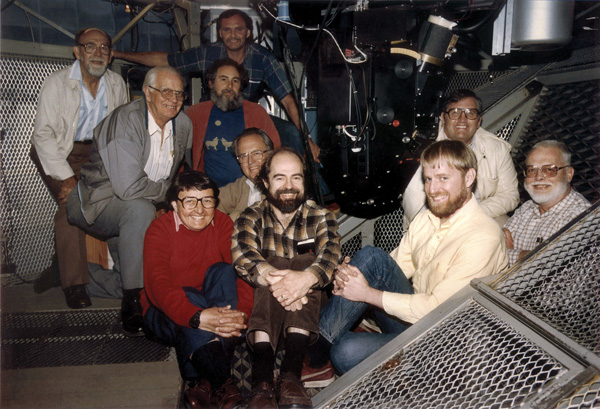

James Gunn (center), James Westphal (far right), and their team inside the Hale Telescope’s Cassegrain cage with Four-Shooter, the prototype for the Hubble Space Telescope WFPC camera, c. 1984. (J. Gunn)

Extragalactic Distance Measurements and Cosmic Expansion

Once the 200-inch Hale Telescope was ready for scientific use, Walter Baade turned it to the Andromeda Galaxy. He hoped to resolve certain kind of variable stars—stars that expand and contract periodically, changing brightness in a predictable manner, which makes them useful for distance measurements—expected to be seen in the neighboring spiral galaxy. His unsuccessful attempt led to a correction in previous distance estimates to Andromeda. The new measurements showed that the galaxy was twice as far as previously thought. To an astronomer, the size of the Universe had just doubled.

Allan Sandage dedicated significant efforts to characterize the isotropy—same in all directions—and linearity of the expansion of the Universe. His value for expansion rate H0 using the Hale Telescope was 75 km/s/Mpc, significantly close to the Hubble Space Telescope's value of 71 ± 7 km/s/Mpc almost 50 years later. In his 1961 paper “The Ability of the 200-inch Telescope to Discriminate Between Selected World Models,” Sandage suggested that the future of observational cosmology would be the search for two parameters: the Hubble constant H0 and the deceleration parameter q0. This paper influenced observational cosmology for at least three decades as it carefully laid out the types of observational tests that could be performed with a large telescope. And roughly 40 years later the discovery that the cosmic expansion is accelerating (q0 < 0) led directly to our modern view of matter-energy in the Universe and the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics (to Saul Perlmutter, Brian P. Schmidt, and Adam G. Riess). The thread of our understanding of cosmology runs squarely through Palomar, and is framed by Sandage's contributions.

Stellar Populations and Evolution

Ground-breaking work at the Hale Telescope by Baade, Jesse Greenstein, Rudolph Minkowski, and others led to the identification of distinct stellar populations of different age and elemental composition, which resulted in a new understanding of galaxy formation and stellar evolution. Greenstein analyzed the spectrum of hundreds of stars to assess their composition (abundances), and he found that some stars were like the Sun in their chemistry, while others contained much higher or much lower amounts of elements such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sodium, and calcium. Greenstein's cataloging of these stellar abundances led directly to close scientific collaboration with nuclear physicist William Fowler, also at Caltech. It was Fowler (along with F. Hoyle, M. Burbidge, and G. Burbidge) who solved the puzzle of how stars synthesize these heavier elements from lighter ones (i.e., hydrogen and helium) in nuclear reactions in their cores, for which Fowler received the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei

The Hale Telescope's extraordinary discoveries extended beyond the Milky Way’s neighborhood, such as the identification of the radio-loud objects 3C 273 and 3C 48 by Maarten Schmidt and collaborators in 1963. These quasi-stellar radio sources, or quasars, were several billion light-years away. They were thus among the most distant astronomical bodies ever observed. Quasars and other luminous variable objects, such as Seyfert galaxies and BL Lacs, today are known collectively as Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) because they are driven by a common mechanism—the accretion of gas by supermassive black holes (a million to ten billion solar masses) in the centers of galaxies. We now understand that most major galaxies, including the Milky Way, have supermassive black holes at their centers, though not all are actively accreting (the 'Active' in AGN).

Technological Innovation

During the 1960s and 70s, infrared astronomy pioneers Gerald Neugebauer and Eric Becklin observed the Galactic center, obscured in visible light by dust, using a single-cell infrared detector on the Hale Telescope.

The modernization of Palomar Observatory began in the mid to late 1970s when Bev Oke, James Gunn, James Westphal, and others developed instruments that used charge-coupled devices (CCDs) for the Hale Telescope. The superior efficiency of CCDs over photographic film substantially boosted the sensitivity and reach of the already powerful “Big Eye.” Gunn and Westphal’s Four-Shooter, an early instrument with four 800×800-pixel CCDs, was the prototype for Hubble Space Telescope’s WFPC camera.

Innovation has continued to be critical to Palomar's success as a leading astronomical research center. One of the principal objectives of the Observatory in the previous and current decades is to produce images of comparable precision to those of space telescopes. Scientific goals such as surface mapping of Solar System bodies and directly imaging close multiple stellar systems, young planetary disks, and extrasolar planets from the ground require technology capable of correcting for the blurring created by atmospheric turbulence. With this in mind, scientists and engineers from Caltech and associated institutions have developed superb adaptive optics equipment for the Hale Telescope, but that are versatile and applicable to other research telescopes.

Graphical Timeline

Hale Telescope graphical timeline ( go to expanded timeline). Time starts in 1920 and flows to the right; use the scroll bar to reach the 2010s. Each column corresponds to a decade, vertical lines indicate years. Darker background shows when the telescope was operational. Each event is shown as a bar whose width indicates time span. Hovering with mouse over an event will bring up a short explanation. Hint: use the keyboard shortcuts (no shift) control/command + to zoom in, control/command − to zoom out, and control/command 0 to reset.

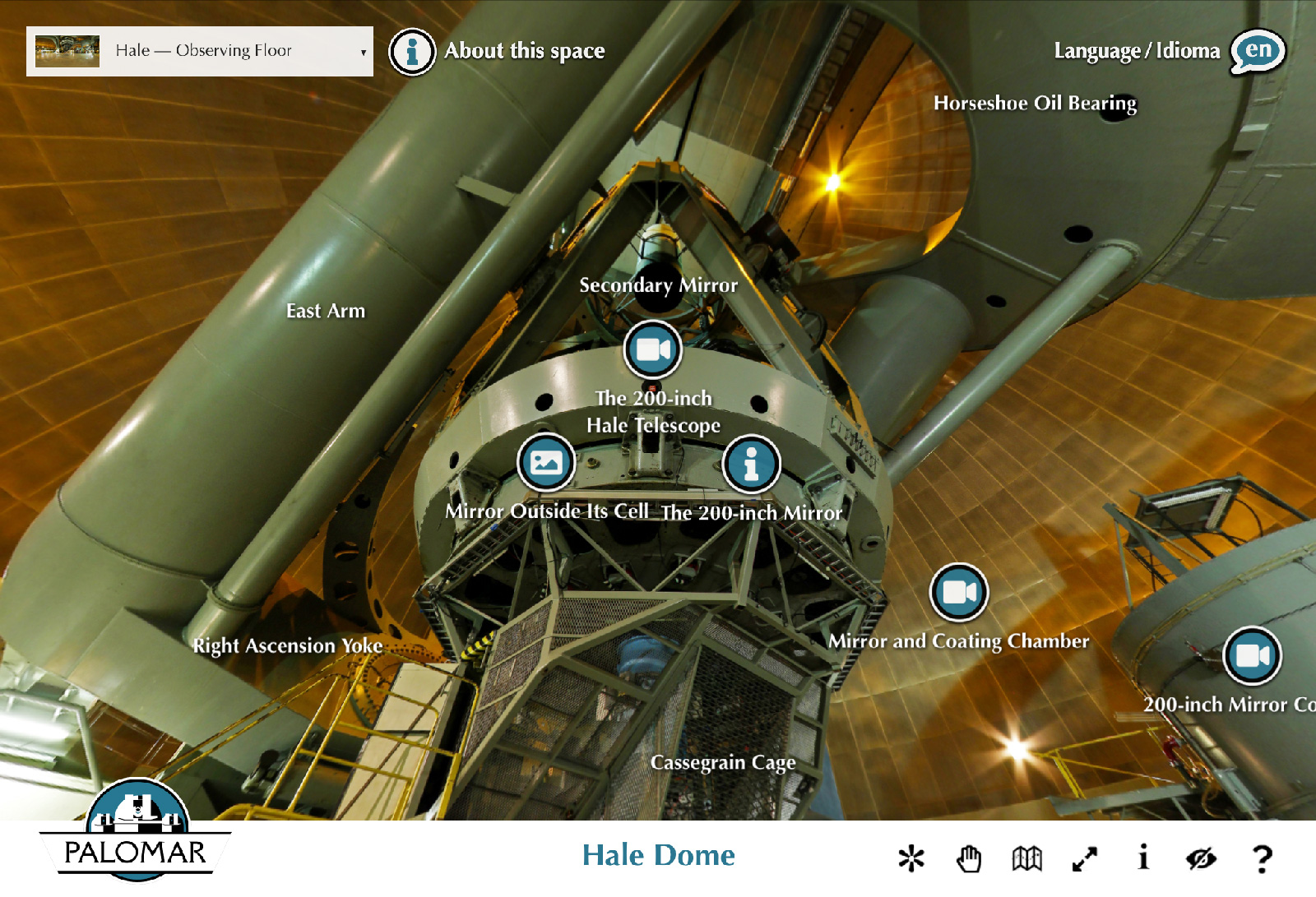

Virtual Tour

This bilingual, high-resolution tour embeds relevant information, images, and video of the “Big Eye.” We recommend viewing the virtual tour on a desktop or laptop in fullscreen mode using the icon in the control bar. While it is possible to view the tour in smaller screens (e.g., large tablets), we suggest using the "lite" version of the tour for screens narrower than 700px (e.g, smaller tablets and smartphones). The lite tour is also VR-enabled, but lacks many of the features found in the full version of the tour. Click here to load the full tour.

Bilingual, annotated tour of the Hale Telescope and its dome, desktop version. (Palomar/Caltech/A.Mejía)

Bilingual, annotated tour of the Hale Telescope and its dome, mobile version. (Palomar/Caltech/A.Mejía)

Media

Hale Telescope Science and Instruments (2020)

Review of the Hale's current instrumentation and scientific programs. Duration: 2:52 minutes. (Palomar/Caltech)

For additional media (e.g., images, videos, webcam) pertaining the 200-inch Hale Telescope, please visit Hale Telescope media, vintage media, and live cams.

Questions? We've answered many common visiting, media, and academic questions in our public FAQ page.

Please share your feedback on this page at the

COO Feedback portal.

Hale Telescope / v 1.0.13

Last updated: 5 August 2025 AFB/RGD/ACM

|

|

|